Presenting a paper at SNEE 2015, Mölle, in the session entitled ‘Trade and Communications in Europe’ with session Chair, Mats Hellström, former Minister of Foreign Trade for Sweden.

Text & Photo © JE Nilsson, CM Cordeiro, Sweden 2015

Name of Author: Cheryl Marie Cordeiro, PhD

Brief author bio:

Cheryl Marie Cordeiro, Research Fellow, is an active faculty member at the Centre for International Business Studies (CIBS), at the School of Business, Economics and Law at the University of Gothenburg. She has a PhD in applied linguistics, with her research interest broadly focusing on Language in International Business.

Acknowledgement: This project on Sweden’s trade relations with China is funded by the Anna Ahrenberg Foundation in Sweden.

Abstract

This two part article traces the qualitative aspects of Sweden-China trade relations from the 1700s, from the time of the Swedish East India Company, to modernity, as exemplified by the case of Chinese Geely acquiring Swedish founded Volvo Car Corporation in 2010. This article leverages conceptually, on the dual structure of world history, that highlights the differences between “international society” and “global society” and uses the example of trade relations between Sweden and China in illustration of a unique relationship between countries that have thus far seemed to find their own equilibrium of both being part of “international society” whilst having between themselves, a long term understanding of collaborating towards an envisaged “global society”.

Keywords: Sweden, China, global trade, international society, global society

Conference programme and article.

View from the conference venue, Grand Hotel, Mölle.

[SLIDE 1]

Good afternoon everyone, my name is Cheryl Marie Cordeiro, from the Business School at the University of Gothenburg.

I’ll be talking about a different kind of trade study today, not so much statistics as it is a narrative entitled:

Waves of trade between Sweden and China: tracing the exchange of goods, services and knowledge between Gothenburg and Shanghai.

It’s a study of the discourse of trade relations between Sweden and China from the 1700s, and how you can see that discourse is currently reflected between the twin cities of Gothenburg and Shanghai, and from the historic and modern narrative, what might we expect to see in future between Sweden and China.

In the summer of 2014, representatives of companies from the Shanghai Juke Biotech Park gathered in Gothenburg to meet with colleagues and partners from Sahlgrenska Science Park. The summer picnic and mingle session hosted in Gothenburg, was part of the on-going cooperation and exchange program between Sweden and China, between the twin cities of Gothenburg and Shanghai, to build a common platform in bio-sciences. It is hoped that the network between the two science parks would encourage joint projects, in view of greater innovation and new product commercialization. This meeting is an example of one of many that has taken place in the increasing wave of exchange of knowledge economy services that has taken place between Sweden and China in the past decade.

But even if the ongoing trade between Sweden and China today is characterized by increasing exchange in the knowledge services sector, the two countries have enjoyed a trading relationship that began in the 1700s. It is only that research between Sweden and China has been small and niche, and understandably so.

[SLIDE 2]

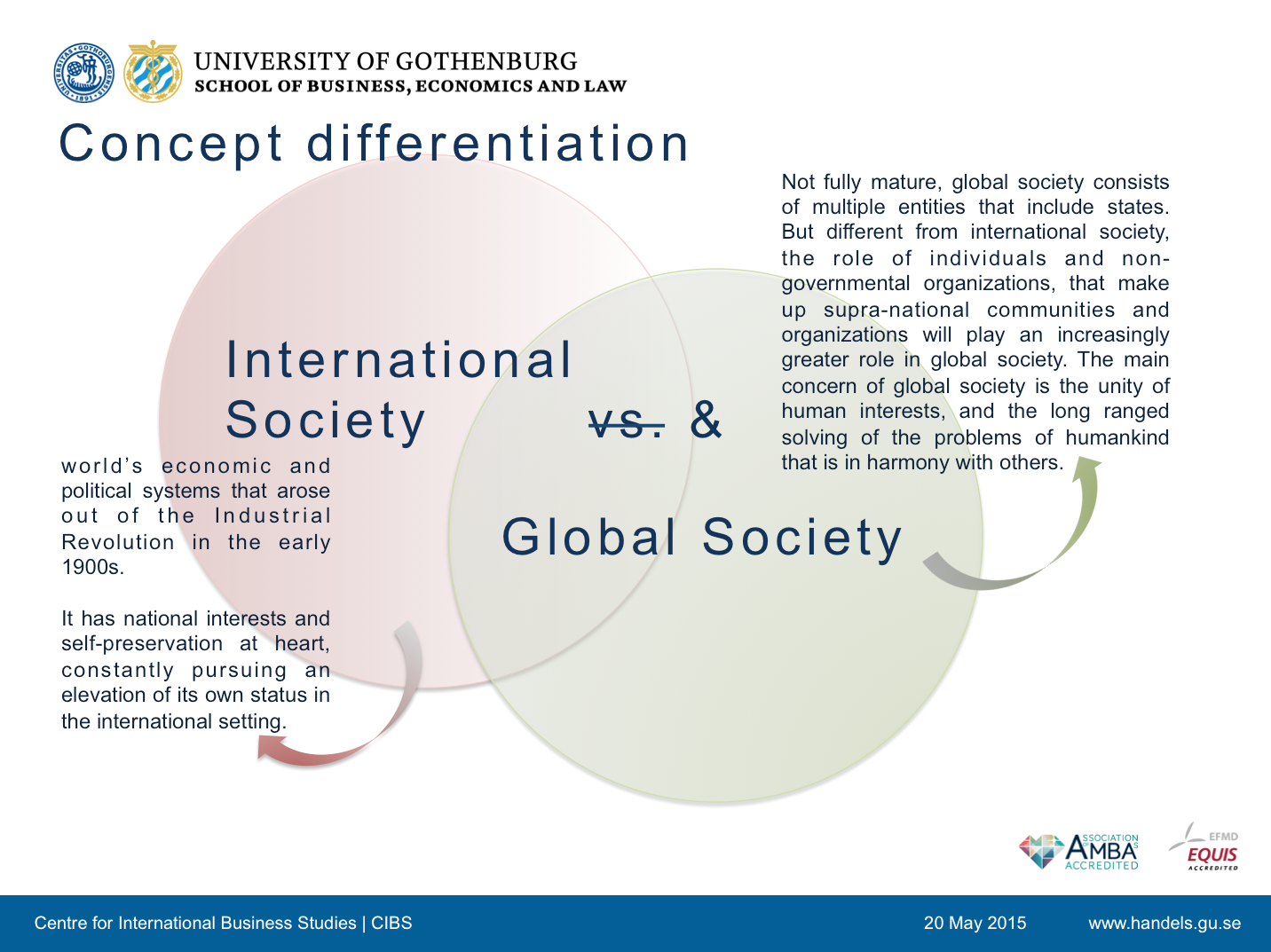

But to begin with a broader perspective than Sweden-China trade relations, and zooming out the research lens, as a reflection of east-west trading relationships in world history, what I’d like to do as first thing is to bring attention to the conceptual dual structure of world history, highlighting the different between “international society” and “global society”. And in the next few slides, I’ll try to show you how Sweden-China relations manage this distinction when working with each other.

The conceptual difference between an “international society” and a “global society” is shown here in slides 3 and 4.

[SLIDE 3. SLIDE 4]

Sweden’s historic trade relations with China can be viewed as a fairly unique relationship between countries that have thus far seemed to find their own equilibrium of both being part of “international society” whilst having between themselves, a long term understanding of collaborating towards an envisaged “global society”.

[SLIDE 5]

Data to this study are both primary and secondary in nature. Primary data consists of (i) interviews with about six key individuals who have worked between Gothenburg and Shanghai from the time of the twin city agreement of the mid-1980s. These individuals, some of whom are today retired, were the pioneers of Swedish multinational enterprises after China’s reform of its market and political framework in 1978.

The information gathered from these individuals lay the foundation of insight into Swedish-Chinese relations from a cross-cultural perspective. Primary data also consists of observations from (ii) study visits to Shanghai and Chengdu.

Interviews were conducted on these study visits with individuals from both the Zhejiang Geely Holding Group (Geely) and Volvo Car Corporation (VCC). The former enterprise had acquired the latter in 2010. All interviews have been transcribed and coded for prominent topics of interest arising from the respondents. Secondary data comprises three main texts that are prominent works previously written on the early trade between Swede and China. This consists of three books in two languages, Swedish and English:

i. The Golden Age of China Trade (Johansson 1992) – essays on the East India Companies’ trade with China in the 18th century and the Swedish East Indiaman Götheborg

ii. Draken och Lejonet (Ottosson 2006)

iii. Shanghai Svenskars liv & oden 1847-2012 (Johansson 2012)

The aim of this study is to analyse the qualitative aspects of the trade relations between Sweden and China, in particular, the twin cities of Gothenburg and Shanghai. The research questions (RQ) include:

RQ1: What commonalities of qualitative trade patterns can be found between Sweden and China from the 1700s to modernity?

RQ2: What insights for the purposes of future steering of trade relations can be obtained from the study of the discourse of trade between Gothenburg and Shanghai from the 1700s to modernity?

The idea of first distinguishing between ‘international society’ and ‘global society’, and second, being able to successfully cultivate a trade relationship with another country based on that innate understanding is one that relates to RQ1 of this study when it comes to identifying the common denominator of understanding in their relationship.

[SLIDE 6]

The long trading relationship between Sweden and China could be said to have to a large extent rested on a basis of asymmetrical socio and political influences, where Sweden could be said to have been more fascinated with China than China was initially, with Sweden.

To the Chinese, Sweden is perhaps just one European country among many – today there are 42 other European countries that Sweden finds itself slotted into in number. It is mainly known for Nobel Prizes awarded in Stockholm, some might have read about the Vikings and Carl Linnaeus in their schoolbooks. Others may think of “the Midnight Sun” or companies such as Volvo AB and IKEA. Even if they might have heard about SKF, few would know that ball bearings originated from Sweden. And all too often, Sweden has been confused with the country of like sounding name, Switzerland.

For Swedes, China on the other hand has long been a familiar concept. Early on, the country came to be associated with various luxury items such as silk and even tea was considered a luxurious item, Europe being too cold to grow any tea plantation at all. Numerous Swedes who had visited China came home with their tales of travel to the land as exotic as it was located in the far east. Swedish poet Evert Taube had composed songs about Shi Huangdi and the Great Wall of China. Sweden could be described as a country that was infatuated with China from the early beginnings of its trade. But unlike any other country, Sweden’s relations with China could be described as having been friendly and diplomatic in terms with mutual peace prevailing between the two. Two political aspects that distinctly mark Sweden’s relation to China are first, that the Swedish government had always distanced themselves from the opium trade, prohibiting Swedes taking part in it, and second, Sweden never had any plans in the course of history till today, to acquire colonies or spheres of influence in China.

[SLIDE 7]

The 18th century could be marked as Sweden’s golden age of trade with China. It was this century that for the first time, Chinese exports could reach Europe by sea, which increased trade volumes to an amount previously unrecorded. The establishment of European East India companies meant that goods from China could reach new markets. The Swedish East India Company, established in Gothenburg on the initiative of Colin Campbell and Niclas Sahlgren, received its first charter in 1731 and from the following year, took over the transport of goods carried earlier by Sweden’s Spanish traders, exchanging silver with China for its valuable products.

It was also during this period that Europe went through the era of Enlightenment and Rococo became fashionable, as a style of art, music and architecture. It was during this time that the Europeans would romanticise the most about China. China had a longer history and a greater cultural heritage than Europe itself that awakened the curiosity and admiration of the Europeans. In literature, it was written that China itself had a very sensible ruling policy, the epitome of true enlightenment.

A contributing factor to China’s allure was Europe’s growing appetite for luxury goods. While it formerly had only been the upper echelons of society who could afford the oriental flair, there were now also groups within the growing middle class who wanted to mark their status with the consumption of Chinese import goods. Tea drinking had already been established as a luxury for the rich from the late 1600s, as was silk the indicator of eastern exotic. Finely crafted Chinese porcelain were sought after in the early 1700s, apart from lacquered goods, wallpapers, fans, pearls and arrack from China.

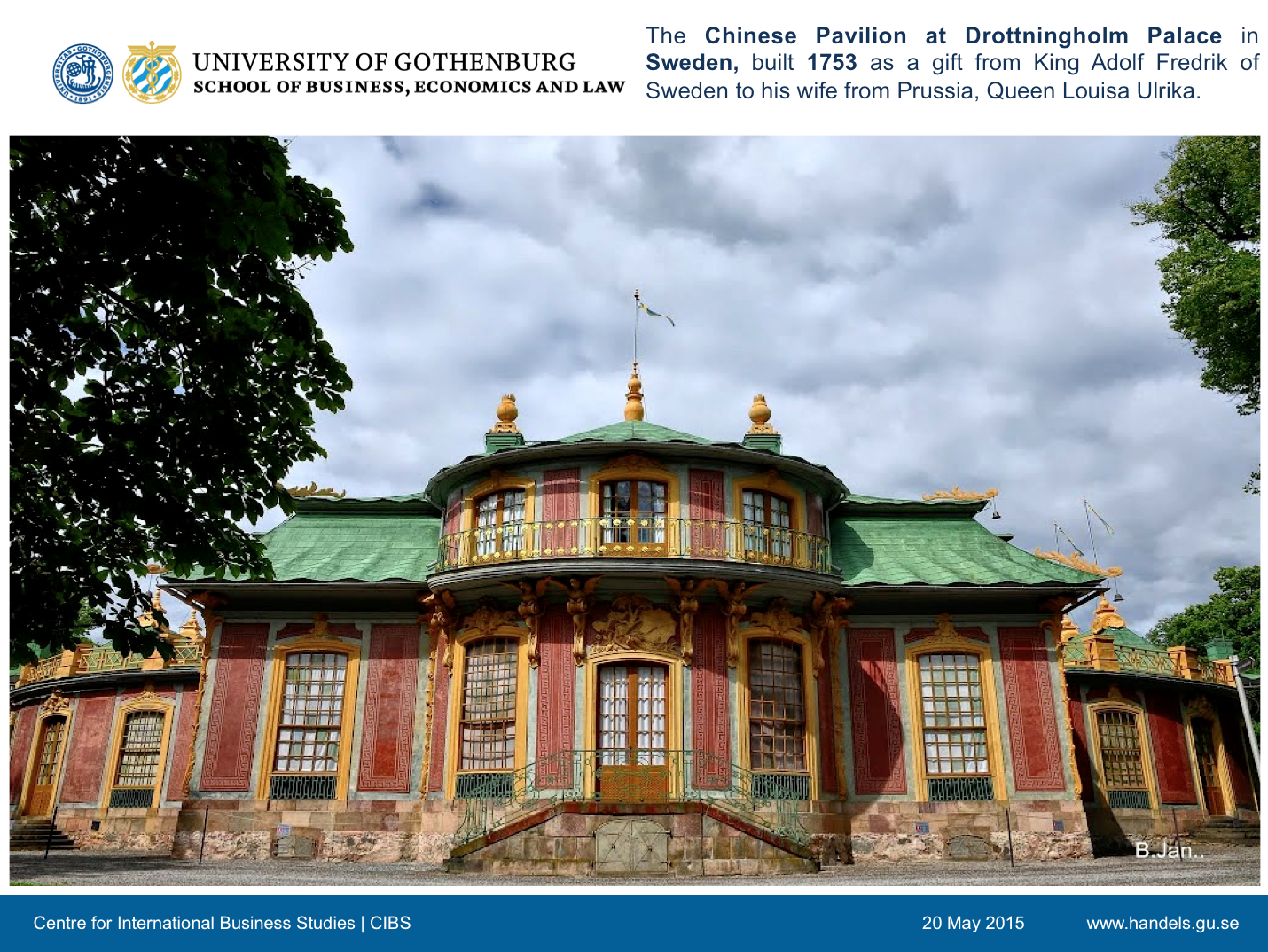

In a broad association, the term “Rococo” in Europe, as well as Sweden, was associated with the polite and graceful manners of the Chinese court etiquette. It soon became ideal to express this admiration in ideology where Chinese art was brought to Sweden in the form of “chinoiserie”. It was a Sino-European mix of taste of the influence of Chinese products and arts that European artists imitated.

Chinoiserie reached Sweden through Europe with the Prussian born Swedish Queen Louisa Ulrika as an important source of inspiration. She had married Adolf Fredrik in 1744 and thus arrived in Sweden. She continued corresponding with her brother Frederick the Great and her mother Sophia Dorothea of Hanover. Her communication with Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire allowed her to follow the cultural and philosophical trends in Europe that she then introduced to Sweden. She had the idea to introduce culturally themed parks in Sweden, in order to create new impressions for visitors and have them expand their imagination in atmospheres created for theatrical purposes. This was the context within which The Chinese Pavilion at Drottningholm Palace was built in 1753. The king, Adolf Fredrik made personal drawings for the pavilion and presented it to his wife. The Englishman William Chambers was given charge to furnish and decorate the interior of the Yellow and Red rooms. He was also employed as a supercargo to the Swedish East India Company and in his service he had the opportunity to have a more realistic impression of the Chinese culture and social life, as other lesser-travelled individuals of the time could. Each room in the Pavilion was decorated with objects brought back to Sweden from China, directly through the Swedish East India Company or indirectly through other European trading companies. The king made sure that the royal Cadet Corps were taught how to drill in the Chinese manner when constructing the Chinese Pavilion and they were dressed in Chinese outfits for the opening ceremony (Setterwall et al. 1972). From this, the Chinese influence soon found its way into Swedish households in the form of porcelain, paintings, and Chinese inspired style of furniture decorated with lacquer or painted material.

[SLIDE 8]

Sweden’s trade with China was founded upon mercantilist principles that encouraged the view that trade in Asia could increase national wealth. But beyond the trade in goods is that most Swedes who visited China in the first waves of trade also belonged to the Swedish Academy of Sciences. These individuals were interested in not just the exchange of goods, but the exchange of scientific knowledge.

Carl von Linné was one such advocator of this perspective and he sent several of his own students to China with the Swedish East Indiamen. He had for example, tried to cultivate exotic plants in Sweden acquired from the east, but due to the climate, did not succeed very well. The findings from some research projects were later put into practice in Sweden.

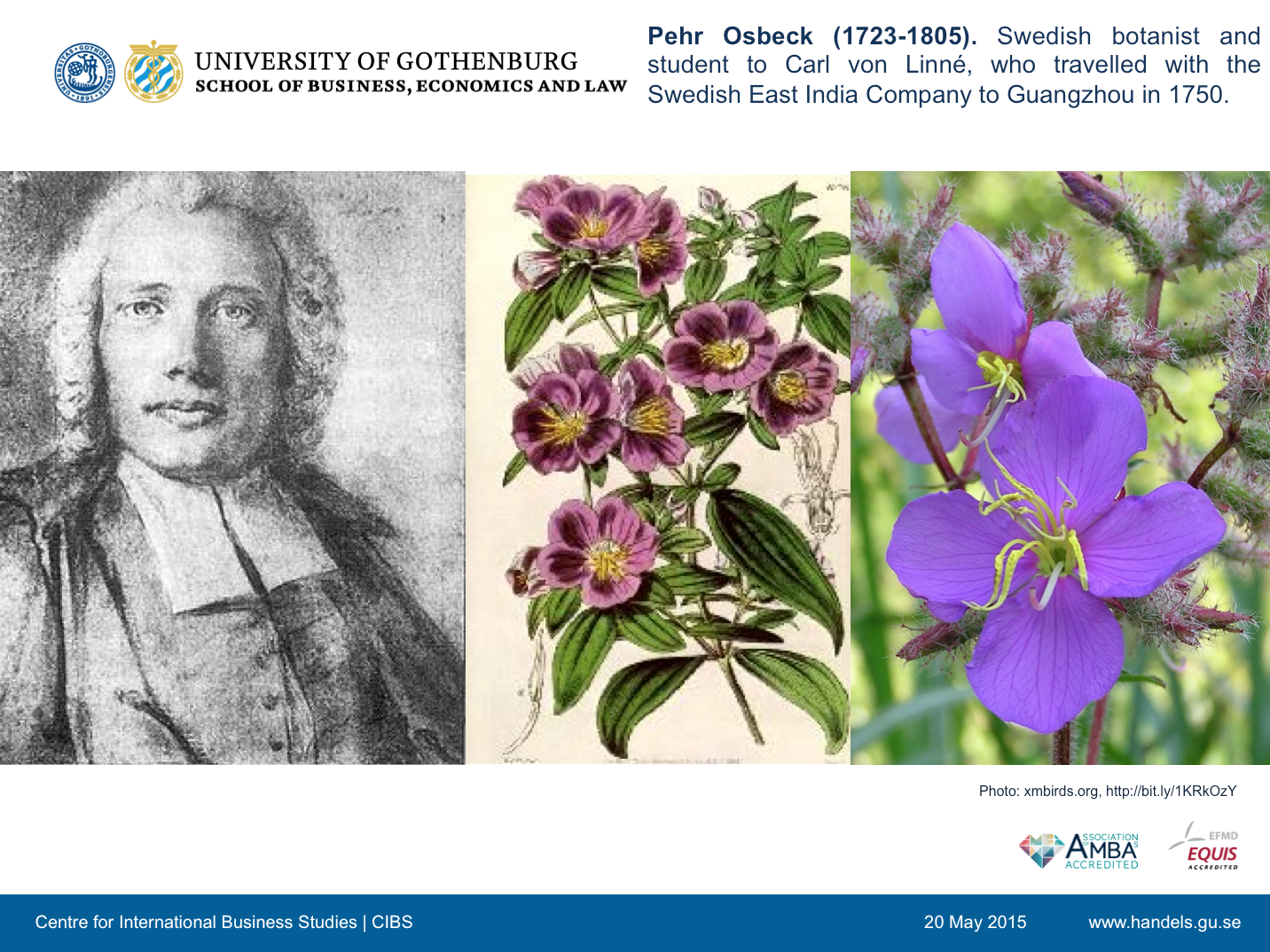

In the early 18th century, the European perspective of China was mostly positive much due to the writings of the French Jesuits and Voltaire. Chinese models and methods in various fields such as agronomy, agriculture and civil service administration were studied and where possible, transferred onto the European context. Another of the era’s botany interested and a famous portrayer of China is Osbeck (1771), who brought home his own “natural history” of the country where he spent 1751-2. In southern China, a plant jinjinxiang received the Latin name Osbeckia chinensis, after Osbeck.

So during the 1700s Swedish contacts with China went almost exclusively in the mark of trade.

Even though the Swedish East India ships carried priests with them, the Swedish priests were not evangelical and had little desire to convert any Chinese to the Lutheran Swedish state church. This mission was left to the Catholic Jesuits and others. And even if the Swedish Queen had much interest in the ideologies and fashion of chinoiserie which she helped disseminate in Sweden, any other real contacts between Sweden and China were minimal, with the two countries having little knowledge of each other’s culture and traditions.

[SLIDE 9]

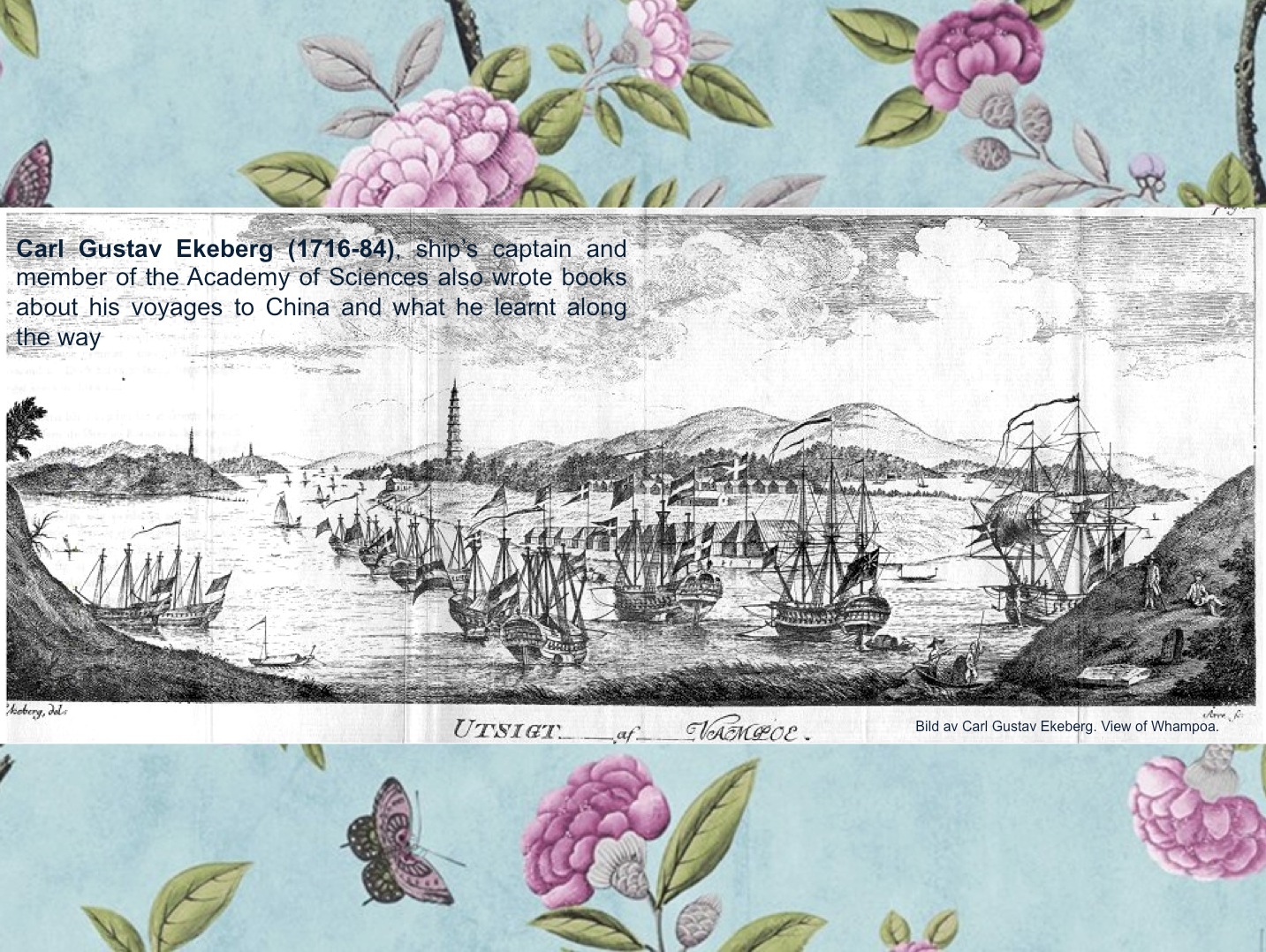

Carl Gustav Ekeberg (1716-84), ship’s captain and member of the Academy of Sciences also wrote books about his voyages to China and what he learnt along the way. Both Osbeck and Ekeberg had the unusual opportunity to socialize with prominent Chinese during their stays in Canton. Their impressions of the Chinese and of China were often fair, with a positive outlook. Osbeck for example wrote that he thought the Chinese were well disciplined and a people who did not take to abusing alcohol. If they did, they would have learnt that behaviour from the Europeans (Osbeck 1771). He also praised the cleanliness of the streets and how the upper class Chinese were parenting their children in a good manner. He was however, amused at the fact that the Cantonese language could sound so boisterous and compared the everyday conversation between the Cantonese people as sounding like a quarrel that would take place in the worst of the taverns found in Europe.

In the course of trade to East Asia the Swedes would arrive late spring or early summer with the ships to China and then stay over the winter. They did not deal personally with their customers because they did not share any language, but instead traded through a middlemen and official interpreters. There was not just a language barrier but culture and weather shocks. The climate in Canton was perpetually hot and humid, with an exotic crowd moving in and out of the customs house wrapped with the scent of incense and followed by a backdrop of noisy musical instruments. Small lizards climbed the walls and you had to keep the windows open to manage the heat indoors. The everyday workwear was very thin, Osbeck describing them as ‘underwear’ that they wore as outerwear. Meals were cooked and served by Chinese staff who also did the daily marketing and at night, you needed to sleep under nets to avoid dangerous mosquito bites. The Chinese were just as curious about these western foreigners and would often stop to look at them, chatting only amongst themselves.

The Swedes were known to the Chinese as “accommodating” people, who followed Chinese laws and regulations. It seemed to the Chinese, that the Swedes were more pragmatic in their approach to business, since to complain unnecessary would reduce the prospect of future business and profits. They had left the protests against corruption to the British who had the greater army behind their words.

But the Europeans spent enormous sums in Canton as the cheap Spanish silver was sold to the highest bidder. Sailors in the Swedish East India Company could also take home both the Company’s products and their own private cargo, called “pacotil”. In this manner, the ships were often filled with so much cargo that they were in danger of sinking, returning to Sweden with porcelain nestled in large amounts of tea, together with Chinese medicine, bamboo and silk. Tea accounted for 85-90% of the value of the goods. It was said in this time trade, there came amongst the people, folklore and stories of important individuals. One such individual was a high-ranking Chinese merchant who visited Gothenburg in the 1700s. It should have been tea merchant Pan Zhencheng (1714-88), who is depicted on the portrait he donated to his counterpart in Sweden. The painting is now with the Gothenburg City Museum. A Chinese interpreter Cai Yafu also visited Sweden in 1786-87 and is said to be have been the first Chinese in Sweden to have been introduced to King Gustav III, who conversed with him in Swedish.

On the side of the Chinese, there were few depictions of Sweden and Swedes in general that were written on a first hand knowledge. Ottosson’s (2006) research indicated that most information has been fragmentary. In a collection of imperial documents of 1747 Sweden and Gothenburg were mentioned in band 298 (out of 300) and the Swedes were called “descendants of the four [nordic] nations.” In an official chronicle of the following year, but published first in 1771, there exists another description of the Swedes. Like the Dutch, Swedes are said to raise their hat when they greet each other and the men use walking sticks “for self defense”. The Swedish habit of using snuff (a habit that is still practiced today) is also highlighted.

[SLIDE 10]

After the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, Rococo had been replaced by Classicism and Romanticism. It was a turbulent era for Europe where many perspectives were reviewed. Strong convictions arose about how things should be and are and with that, tolerance to what was foreign, succumbed. The west began to view China’s Qing Dynasty as “uncivilized” and “barbaric”.

In the perspective of Ye’s dual structure of world history, it would seem that this would mark Europe’s inward turning towards the principles of “international society” where the philosophies of the Enlightenment scholars and their unqualified admiration for China were replaced by publications that contained a more negative view of the country. In 1804, “Travels in China” by geographer John Barrow who participated in Macartney’s failed mission to China was published with the purpose:

“…to shew this extraordinary people in their proper colours, not as their own moral maxims would represent them, but as they really are—to divest the court of the tinsel and the tawdry varnish with which, like the palaces of the Emperor, the missionaries have found it expedient to cover it in their writings; and to endeavour to draw such a sketch of the manners, the state of society, the language, literature and fine arts, the sciences and civil institutions, the religious worship and opinions, the population and progress of agriculture, the civil and moral character of the people, as may enable the reader to settle, in his own mind, the point of rank which China may be considered to hold in the scale of civilized nations.” (Barrow 1804:4)

The founding thoughts with the tendency to classify and evaluate people according to race, region and skin colour were laid in this era even if these thoughts did not fully take ground till later in the century.

Most important was that not everyone shared this upcoming perspective and throughout the 1800s, there were numerous indications that Swedish authors and scholars continued to write positively about China and its culture.

These included August Strindberg (1849-1912) who was a very prominent writer in Sweden of the time.

Set within the context of mutual commercial interest, that lends a supporting view towards Sweden and China’s unique relation in history that orientates generally towards the principles of “global society” is how the two countries navigated their relations during the Opium War.

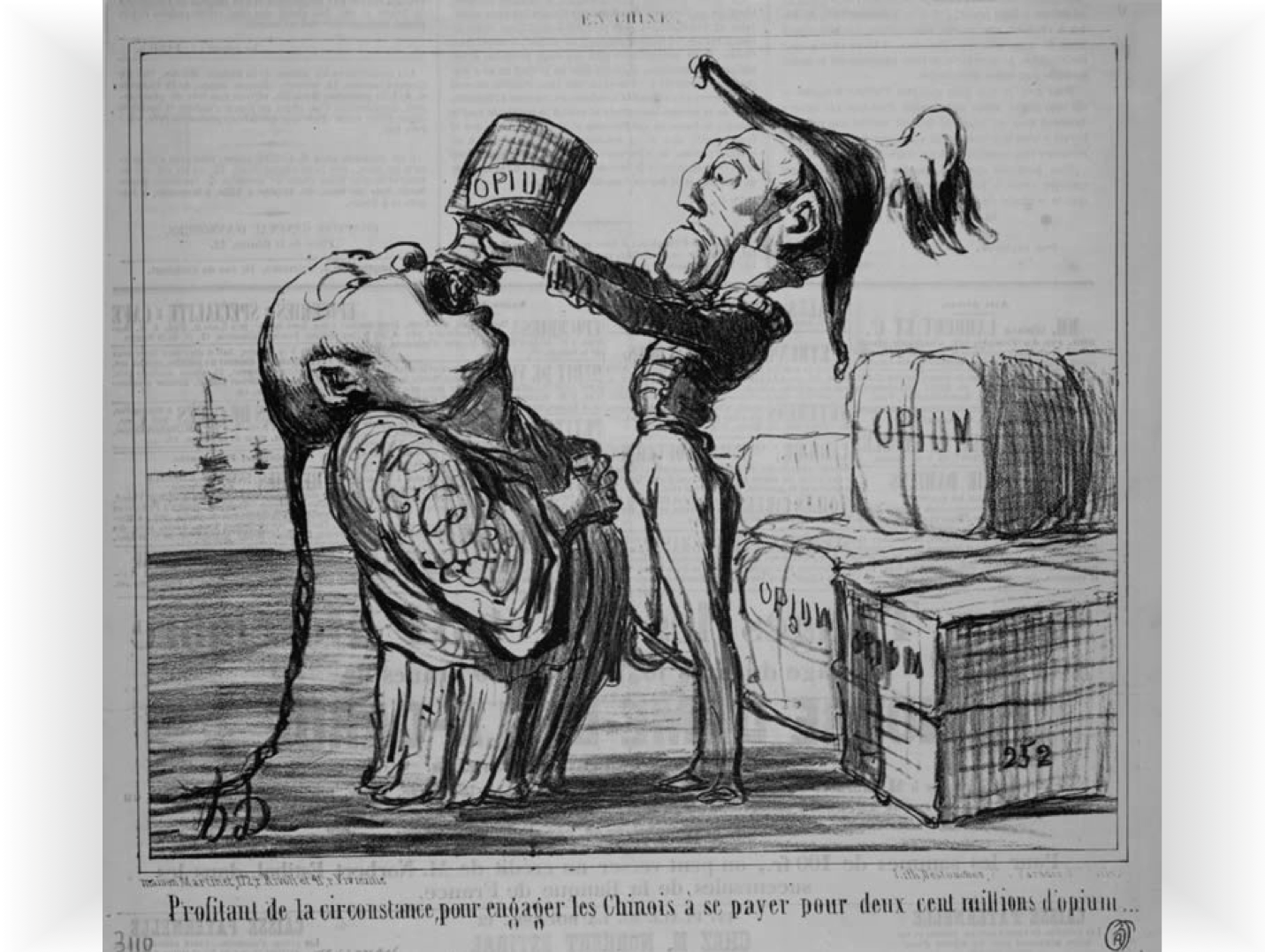

[SLIDE 11]

Although opium was known in China since the 7th century, it was not till the 17th century that the mixing of it with tobacco for smoking introduced to China by the British that problems mounted on several levels. In the century of 1729 to about 1829, China saw its import of opium rise at an exponential rate. Apart from the disastrous national health that it would cause, the illegal import of the substance was paid in silver that had the consequence of inflating the prices of precious metals. In a land base of mostly agriculturalists, the farmers who lived with copper but had to pay taxes in silver, this led to a certain financial ruin.

In 1839 Governor Lin Zexu enforced what may have been history’s biggest drug seizure when he destroyed one thousand ton of British opium. That same year an armed conflict erupted between Great Britain and China. This became known as the “Opium War” that ended with a military defeat of the Qing dynasty, who was forced to sign the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842 and yield Hong Kong to the British. China also had to pay a large compensation for all destroyed opium. The five cities so-called “treaty ports” were opened for trade with the west, amongst others the rapidly expanding city of Shanghai. China was forced to accept a series of unequal treaties, not only with the British but also with a number of other western great powers, such as France and the United States. Soon other countries joined in.

[SLIDE 12]

In retrospect, the west perhaps would have needed to have reacted more sharply on British dealings with China. Even the more positive and neutral Sweden seemed to have failed on this account. Swedish historian and merchant Anders Ljungstedt (1992) admitted for example that the opium trade was “less honorable” but he still did not condemn the industry that gave profits to his English business friends.

The Swedish government was quick to back words with action. After the Opium War, Carl Fredrik Liljewalch (1796-1870) was sent as Swedish ambassador to the Qing Dynasty. He was a skilled negotiator and announced to his counterpart Qiying (1790-1858), Viceroy of Guangdong and Guangxi that he simply could not return to Sweden unpunished without an agreement with China. The argument gained a hearing and 20 March 1847, in the fourth day of the second month of the Daoguang Emperor – 27th reign, the first treaty ever between the two countries was signed. Since Sweden between 1815 and 1905, was in union with the neighbouring country of Norway, the treaty was signed treaty between Da Qing, then China, and “The United Kingdoms” of Norway and Sweden.

The agreement was almost a copy of the unequal treaties the empire a few years earlier had signed with the U.S. China lost the right to freely set tariffs on Swedish goods. Swedish citizens became ‘extraterritorial’ and could not be brought to Chinese court if they committed crimes but must be judged by its own consular court. Sweden also had unilateral most favoured nation status. It became possible for Swedish and Norwegian warships to call at Chinese ports to “inspect the trade.” In the following years, China would conclude similar agreements with practically all western countries.

Despite these treaties, Liljewalch however, was in no way hostile towards China. After returning home, he wrote a trip report in which he praised much of what he had seen in the country. He turned amongst others against the new image in Europe of China as a tyranny with severe penalties and talked about misunderstandings and exaggerations. The tolerant nature of the Chinese was emphasized. But like many of his contemporaries, Liljewalch failed to condemn the opium trade. He even stated in his report that opium could be good for health. A moderate use of the goods would “strengthen and cheer” and it was more dangerous to drink brandy. However, there were many in Sweden who saw opium traffic with disgust and from the onset, the government prohibited Swedes and Norwegians take any part in the drug trade.

[SLIDE 13]

The main point in Sweden’s official stance towards China during the Opium War was different from that of other western countries. Sweden was not among the powers who divided China into “spheres of interest” or “extorted leases”. The government in Stockholm had really no plans to acquire possessions in countries far away. On the contrary, Sweden sold its last colony, the Caribbean island of St. Barthélémy, year 1878. Still, it took awhile before the unequal treaties could be revised to the benefit of China. In 1908 the treaty between Sweden and China so that the Chinese were given the same rights in Sweden as the Swedes enjoyed in China. The concession was mostly symbolic, but it showed the way for other powers in the future. Article X of the second paragraph was that the Swedes extraterritoriality could be abolished, but only “as soon as” all other treaty powers had waived theirs. This shifted the issue into the distant future.

During the first decades of the 1900s the nationalist Chinese movement awoke in earnest. The requirements for the renegotiation of the unequal treaties became louder and louder. The First World War weakened the European powers, especially Germany, which in 1919 had to give up all treaty rights in China. Soon also withdrew Soviet Russia voluntarily from theirs. Pressure on other powers to allow auditing of the old agreements became very strong. When China had been unified and got a central government in the late 1920s the western powers reluctantly initiated talks with the Kuomintang officials. The result was that most people, including Sweden, in 1928 abstained from a number of previous privileges in the country. China regained its sovereign right to determine the tariff policy and allowed most favoured nation treatment.

[SLIDE 14]

Moving on into the early 1900s, Swedish business relations with China ran parallel to its political relations where the early 1900s saw a flourishing of Swedish business enterprises in China, beginning with Shanghai.

These enterprises were established mostly with the help of a Chinese agent, though in later years, Swedes began to establish companies of their own accord through individuals who had contacts in the region such as Gustaf Wallenberg and Olof Wijk (Johansson 2012). In 1936, companies from Gothenburg with agents in Shanghai included Ekman & Co AB, the Swedish East Asiatic Co., Transatlantic Steamship Co. and SKF Ball Bearing Co.

AB SKF was founded in Gothenburg in 1907, growing rapidly to become the largest employer in Gothenburg. International expansion was to come for the company and in 1912, it opened an office in Shanghai via an agent, founding a subsidiary owned Chinese SKF Co. Ltd. In 1916. The enterprise established a subsidiary in 1915, AB Volvo who considers itself officially founded in 1927 when Volvo Cars rolled out its first ‘Jakob’ in Hisingen, Gothenburg.

[SLIDE 15]

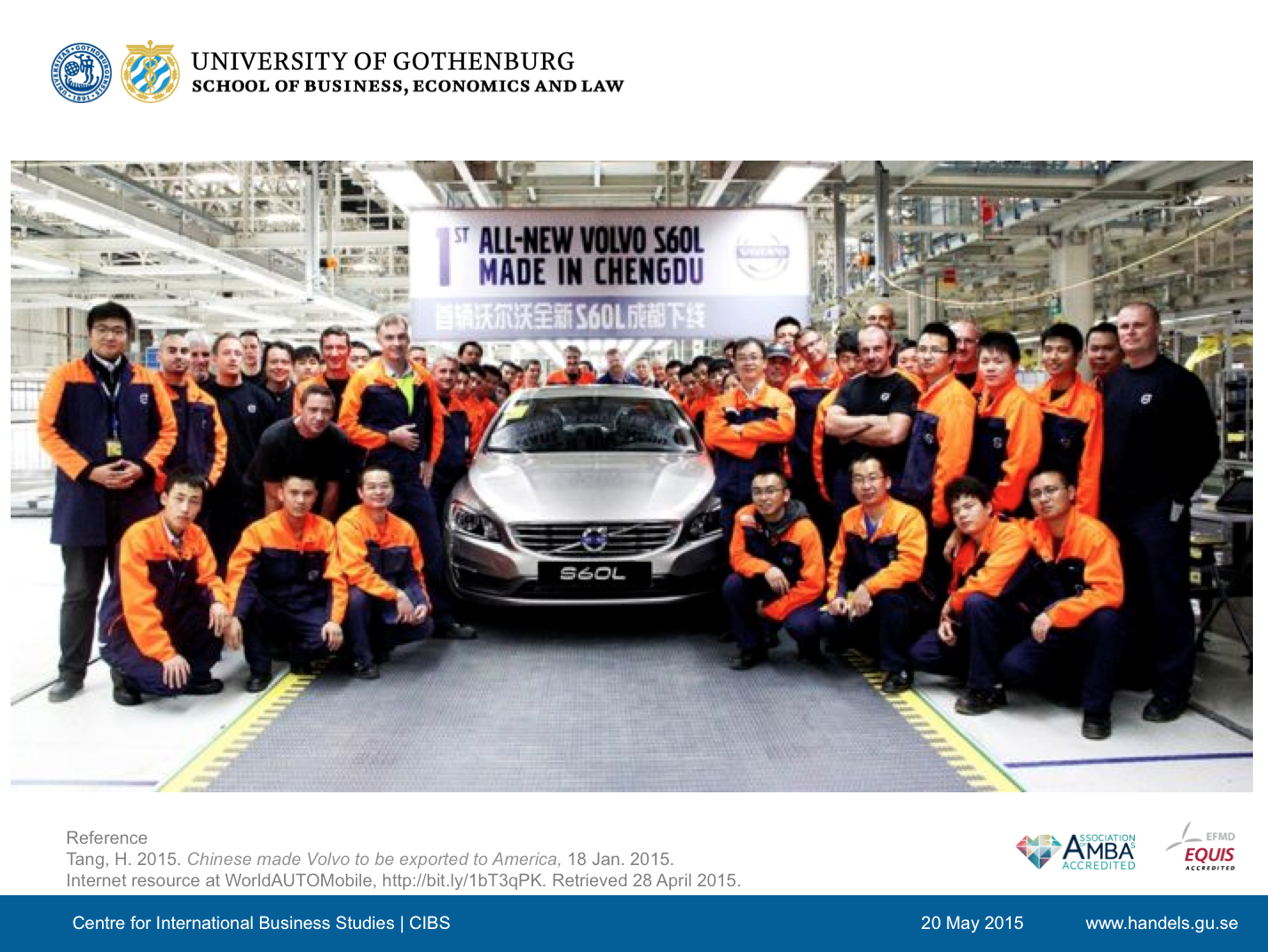

Since AB Volvo’s established presence in China in the 1980s, the most exciting news in the past recent years would be the Chinese acquisition of Swedish founded Volvo Car Corporation (VCC) in 2010 that marked interlacing layers of trade of products, services and most notably of all, knowledge between the two countries, especially between the twin cities of Gothenburg (founding home of AB Volvo) and Shanghai (headquarters of the Zhejiang Geely Holding Group, Geely, that today owns VCC).

Geely had very humble beginnings. The personal story of its Chairman Li Shufu who lived out in the farmlands and began building refrigerators from spare parts, and then moving on to building motorbikes, where building cars was his dream, and owning Volvo Cars was an even larger dream of his, turned into reality, has inspired people the world over. But in this contextual background is the noticeable gap of knowledge. Not only technical knowledge where Geely is known to build cars for lower segments of the market, but also people management skills. There was a layer of middle managers in the Chinese context that is still not currently filled and there is also the aggressive turnover rate in China.

This gap in which knowledge and skills can be transferred is currently what is defining the trade in the knowledge intensive services sector between Sweden and China, and in particular, what Gothenburg has outlined in their Memorandum of Understanding (MOU)

[SLIDE 16]

Taking the case of VCC in China, and in my own research interest, the continued interaction between Sweden and China in these companies, how they work together, is reflected in the management of VCC in China.

There were many uncertainties at the time when Geely was to acquire Volvo (GTC 2014, Andersson 2012). As much as the European market wanted to keep VCC a separate entity from Geely, due at the time of concern of safety and quality standards, the Chinese market had likewise concern, that Geely as a brand should not be conflated with VCC, due to the differing market segment base.

In that sense, the first ‘big surprise’ came in the form of VCC having autonomous decision making capacity, from their Chinese ownership. Li Shufu who is known to have a poetic side and is said to view Volvo as tiger that needs to live free (SvD 2015), has taken this vision to the practicalities of how VCC is managed in China. This process was described as a paradigm shift in attitude within VCC, of how they were to function and develop in China, where they felt as if they had come home into themselves again, being able to create and innovate at will, towards profitability.

The current autonomy experienced by VCC also encouraged the business enterprise to continue its operations based on its founding core values of focusing on people, its customers, and the environment.

Five years on from China’s acquisition of Swedish founded VCC, there was nowhere made clearer than from the three study visits between 2010 and 2015, with interviews held with key individuals who worked in Geely and VCC, how Sweden and China have managed to steer their co-working in China.

Knowledge sharing comes in many more forms than technical knowledge transfer. While Li Shufu believes that Geely has already benefited from technical knowledge transfer between VCC and Geely (SvD 2015), what is revealed by a visit to the various VCC plants in China is how much Swedish top managers in China invest time and effort in fostering VCC corporate cultural values. Corporate cultural values form a foundation upon which product quality standards as well as talent retention is built, forming part of the VCC branding strategy both in terms of product branding and employer branding.

[SLIDE 17]

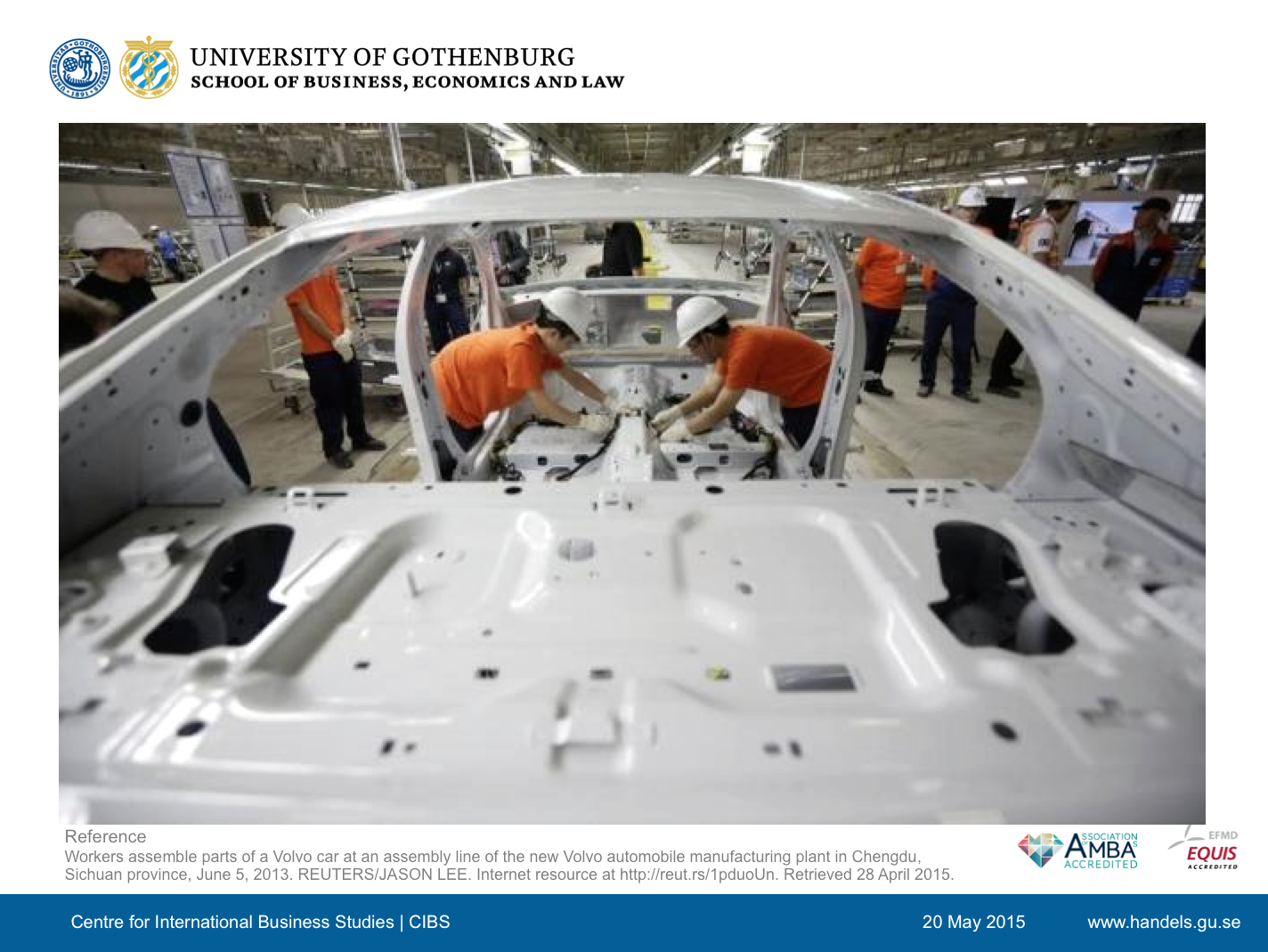

As an example of socio-cultural knowledge transfer, when Swedish top managers who worked in China were asked “What is different in terms of managing people in Europe as compared to managing people in China?” The general reply was that there was not much difference in the approach towards managing a workforce. Whether in Europe or in China, VCC puts the safety and interests of employees high on the priority list.

As a means of looking after its workforce, a stringent measure that VCC takes is keeping to the highest possible quality standards, from not overworking individuals to keeping individuals safe on the factory floors with its ‘Vision Management’ strategy that allows any manager a 360 degrees unobstructed view of the factory grounds in order to be at any point on the factory floor in under two minutes. In the Chengdu manufacturing plant, this is achieved by glass walled offices, and having all equipment at no higher than 160cm from the ground. So far, the factory plant has registered fewer accidents in the last two and a half years with ca. 2,500 employees on the ground, as compared to its plants in Europe.

Keeping to stringent standards pertained also to team leadership training. Beginning with thirty team leaders in total, it was made sure that no more than twenty to twenty-five new individuals were recruited into the training programme. When the team leaders grew to ninety in numbers, eighty new team leaders in training were recruited. The strategy of not expanding too rapidly ensured that no one had more than one trainee to manage at a time, “because we don’t want to wake up one morning and have 2,000 employees who didn’t get the right training from the beginning.” What was important was for every employee to understand why they did what they were doing, and once that knowledge was internalized, it would be the employees themselves who would then teach newcomers about VCC’s quality standards and procedures.

People in China were treated no different than those in Europe. What a team leader on the front line of the manufacturing plant did in Europe for example, was also expected of a team leader in China. A consequence of this expectation was that the team leader in China would be more involved in problem solving, compared to team leaders in neighbouring factory plants under different management.

[SLIDE 18]

What can be observed as a constant discourse or narrative of trade relations between Sweden and China is respect of individual autonomy, and a non-colonizing attitude towards the other. There is always an underlying mutual respect, of working with each in a global society mindset, whilst very much maintaining each nation’s sovereignty.

The significance of this observation of the trade relations between Sweden and China is one of future trajectory. Though not easily accomplished and with an understandable numerous factors to consider, that it is nonetheless possible for countries to work in mutual support of one another, navigating around most of “international society’s” hegemonic structures.

In this sense, Swedish-Chinese trade relations and the continued cooperation between the cities of Gothenburg and Shanghai could be said to encompass a unique discourse, defined by mutual respect in exchange of commodities, services and in the latest wave of trade, of social and technical knowledge.

[SLIDE 19]

Thank you!