In Chapter 4, the coding procedures indicated that the Organization category contained the largest number of topics. The coding procedures helped to highlight certain topics within that category more than others and the topics could be further grouped together to form larger concepts. The two larger concepts that emerged from the axial coding of the Organization category, and that seemed to interest more than 50% of both groups of the respondents include the concepts of hierarchy and assimilation / integration. Four texts in total were selected and presented in Chapter 4, section 4.2.3. Two texts for each concept were selected, one from a Scandinavian respondent and one from an Asian respondent, in order to get a corresponding point of view.

This chapter will use the linguistic framework outlined in Chapter 3, to explore the concepts of hierarchy and assimilation /integration in greater detail. For the concept of hierarchy, Examples 4.k and 4.m are texts that will be explored further with the linguistic framework in this chapter, and Examples 4.n and 4.p will be explored further on the concept of assimilation / integration. The text examples shown in this chapter are chosen following the criteria / procedures outlined in Chapter 3, section 3.6.5, the main reason being that the text needs to be relevant to the topic of analysis and that the respondent would have needed to speak about the topic at length in order to apply the SFL framework.

As a brief recapitulation from Chapter 3, section 3.6, each text will be analyzed according to four dimensions:

i. Interpersonal – appraisal analysis, which is an analysis of the speaker’s judgements, opinions and feelings as revealed by their linguistic choices and features of the text.

ii. Ideational – transitivity analysis, which is an analysis of the speaker’s ideas and experience, their processes of doing, saying, sensing and being.

iii. Textual – theme analysis, which is an analysis tracing the speaker’s logical development within the clause structure and what the speaker is most often foregrounding in terms of topic.

iv. Words in context analysis – based in discourse analysis, this section uses a computer software to help locate the words as they occur in context. The purpose of this is to analyse how the speaker uses a particular word in context and what the word is associated with from the speaker’s point of view.

5.1 Hierarchy

5.1.1 A Scandinavian point of view: analysis of text Example 4.k

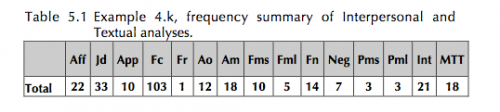

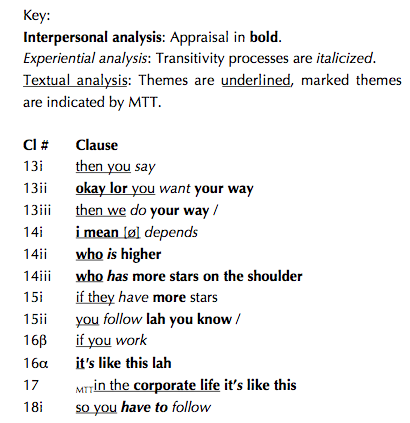

As the interpersonal, experiential and textual analysis (the SFL analysis) is extensive, a more detailed text analysis of Example 4.k can be found in Appendix 5i 4k. A full table containing the three dimensions of analysis that tabulate the number of occurrences for various features, can be found in Appendix 5A, where Table 5A (i) shows three metafunctional levels of analysis and Table 5A (ii) shows the transitivity analysis sorted according to the various types of transitivity processes. Table 5.1 below shows the summary of the interpersonal and textual analyses, from Appendix 5A (i). As all three metafunctions are closely intertwined in language, this section (as with the following sections of analyses with the other text examples) will discuss the dimensions of interpersonal, experiential and textual analyses simultaneously.

There are altogether, 140 clauses in Example 4.k. Each column in Table 5.1 reflects the number of clauses out of 140 that contain the following interpersonal and textual features.

The interpersonal index total from Table 5.1 is 241. The number 241 is derived by adding all numbers from the columns in Table 5.1, except the last two columns of “InT” and “MTT” which are the numbers for the textual analysis. About 43% or slightly less than half of the interpersonal dimension of M’s talk is amplification (focus and force). Judgement, appreciation and both comment and mood adjuncts make up about 30% of M’s talk. Words that indicate affect make up about 10% of M’s talk, perhaps indicating that M as an individual was not too affective in her speech.

The transitivity analysis in Table 5A (ii) in Appendix 5 shows that 60 out of 140 clauses or 43% of the text are material processes. The high number of instances of material processes indicates that in this instance, M was focused mainly on telling about the processes of doing and other activity processes. 15 of the 60 material processes or about 25% of the material process clauses have M herself as the doer of the action. In some instances, M was also the agent of the process, where M was not only in charge of the activity but was the person putting into effect, the activity processes (italicised) such as, “…so i changed that to three / which mean i couldn’t take away titles / because that would be very sensitive / but i tacked them in three main levels and i took away all links to annual leave days”. The actors they were also noted by M when she witnessed that some employees were beginning to take on larger roles within the organization, “…two actually definitely grew into the costume …and they started to make their own decisions”. Mentally and relationally, M noted changes in her employees too, “…they started to be creative / they started to be unafraid”.

Ellipsed agents or actors [φ] , are also often found when M poses a critique towards the Singapore-Chinese mentality in working, so as to either soften the critique or to avoid directly naming an individual, for example, “…but history always forms a country’s traditions / and of course if / if you were killed [φ] or removed or head chopped off [φ] because his head was chopped off [φ] / then it became quite dangerous to do anything else than you were ordered [φ] to do”, where the symbol [φ] indicates an unknown actor that is perhaps recoverable from context i.e. the Chinese emperor or the Singapore government or the local Chinese boss, though these are still not explicitly mentioned.

The large number of material processes is followed by an almost equal number of 53 or 38% relational process clauses. This indicated that what M was also concerned about was the state of the affairs at certain points in time within the organization, concerning the attributes and qualities of her colleagues and employees for example. M’s explanation of the original state of affairs of the organization having nine hierarchic levels when she arrived is characterised by relational and existential processes, “…and at that point in time / there were more or less nine hierarchic title levels in the office …all levels also had a number of value of annual leave days / as an officer you had one more day than a junior …but in the office back home / we have three”.

There were 18 or 13% mental process clauses in the text, which focused on M’s thoughts on the creativity of her employees and how she could best prepare them in expanding their roles within the organization once she was in charge. The mental clauses with alternating sensors of M (“I”) and her employees (“they”) found towards the end of the text example, “…so before i couldn’t see at all that they have this / er helicopter view / i didn’t realise that they could / they had it / but i’ve told them okay this is your chance / you have to do what you want to do with it / and as i said / two actually definitely grew into the costume / i enjoy this / and they started to make their own decisions / they started to be creative / they started to be unafraid”, show a certain sense of working dynamics between M and her employees where both sides were able to learn from each other and come away with a sense of satisfaction at work. In general, the mental clauses show M’s sense of accomplishment with a change in mentality and attitude in her employees towards what can be done on the job, in her years at the organization.

There were fewer verbal processes and existential processes, with 6 and 2 clauses out of 140 clauses respectively. One of the existential clauses goes back to a strong theme for M, the hierarchic levels found within the organization when she first took over in 1998, “…and at that point in time, there were more or less nine hierarchic title levels in the office”.

In terms of affect, M used amplification most frequently when speaking, a closer look at the clauses that contained a high frequency of the use of amplification will give an idea of the attitudes emphasised by M and she deemed as important enough to emphasise when talking about hierarchy within the organization. An analysis of the transitivity processes within these clauses with high frequency amplification will also lend an idea of which participants were involved in the processes.

Appendix 5A shows that the amplification of attitude can be found in clause clusters throughout Example 4.k. Within these clause clusters of focus amplification use, there are also clauses that contain more than one use of focus amplification per processing unit, where in these cases, M possibly wished to emphasize a certain point. The following paragraphs will show some of the uses of amplification in Example 4.k and in which context they were used.

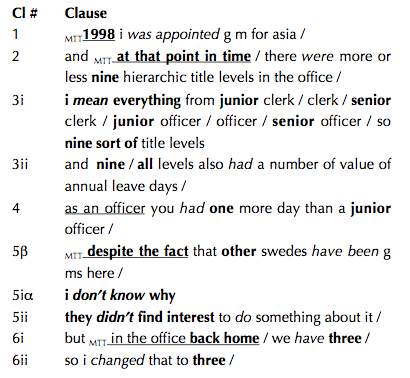

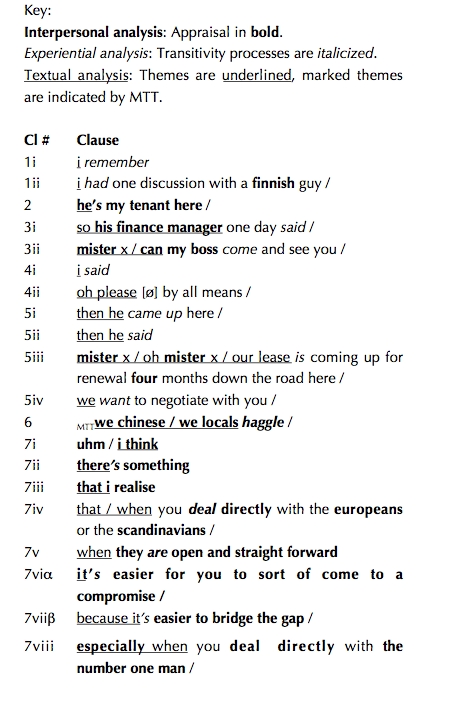

Focus amplification is used first by M, from clauses 1 to 6ii, when she begins to explain the hierarchic situation she encountered within the organization which she took over in 1998:

Key:

Interpersonal analysis: Appraisal in bold.

Experiential analysis: Transitivity processes are italicized. Textual analysis: Themes are underlined, marked themes are indicated by MTT.

That M was not entirely happy with the situation in the Singapore organization when she arrived in 1998 (a marked theme), as general manager is evident through clauses 1 to 6ii. M’s point of view that the nine hierarchic levels within the organization was a problem is shown in 2 to 3ii, where her extensive elaboration and reiteration of the words nine…levels in 2, 3i and 3ii perhaps reflecting a frustration M feels about the situation at the beginning. The use of affect through 5β, 5iα and 5ii is indicative of M’s frustration, bewilderment and disappointment at her predecessors and other Swedes who were general managers prior to 1998. 5β for example could be considered a marked theme She not only makes a distinction between herself and other Swedish leaders prior to her take-over and mentions explicitly that something should have been done about the hierarchy structure. She explicitly questions the actions and passes judgement on her predecessors’ actions as uninterested in 5iα and 5ii.

She then took it upon herself as leader, to make a change to the organization structure as shown in the material process in 6ii. The result of her taking action was three hierarchic levels within the organization, similar to what M recognized from the organization in Sweden.

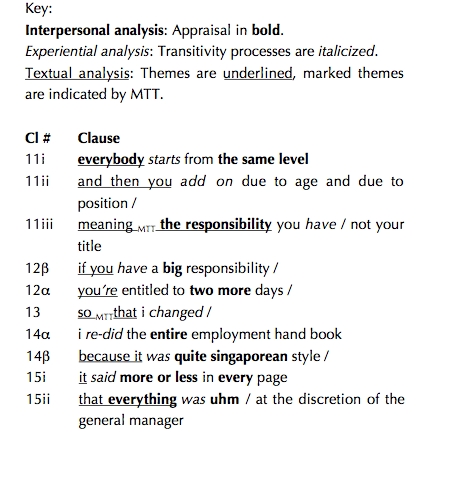

Amplification is also used in the cluster of clauses when M speaks about the structural changes she has made within the organization with a redistribution of responsibility with the changes in hierarchy.

What M emphasizes in lines 11i to 15ii, are consequences to the flattening of the hierarchy within the organization and how employee rewards are pegged thereafter. What was important for M was that the result of flattening the hierarchy meant that a more egalitarian aspect to the organization structure could be introduced, where everyone started on the same level. The concept of one’s responsibility, as indicated by a marked theme in 11iii, is introduced and that one’s employee benefits were pegged in accordance to how large a responsibility one had within the organization.

Though there seems to be no explicit affect shown from 11i to 15ii, M’s discomfort and strong feelings towards the Singapore style of working is highlighted by M’s use of focus words on the issue in 14b to 15ii with words such as quite, more or less, every, everything … at the discretion of the general manager. And it was this existence of a vertical hierarchy and a central decision maker, as opposed to delegated responsibility, that motivated her to re-do or re-write the organization’s entire (in 14a) employment handbook. The marked theme that in that i changed (in 13) serves to show that M considered it important for people within the organization to take on more responsibilities.

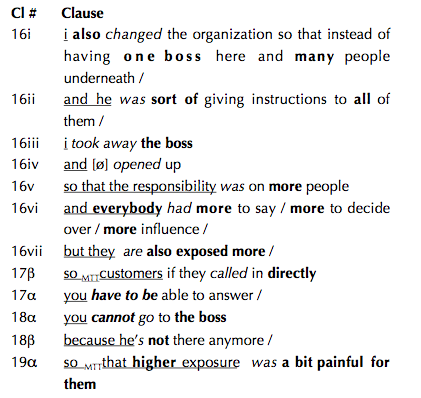

Reorganization of the vertical hierarchy within organization, into a more lateral hierarchy had consequences for the employees in terms of the scope of their daily responsibilities:

In 16i to 19α, what M emphasises through the repetitive use of the word boss in one boss (in 16i), the boss (in 16iii and 18α) is the existence of a central decision maker with an authoritarian approach to leadership style who gave instructions to many (in 16i) and all (in 16ii) people in the lower rungs of the hierarchy.

The resulting lateralization of hierarchy within the organization meant this one boss would no longer be there, as described from 16v to 18β, mostly with the use of negatives for emphasis such as cannot go to the boss, he’s not there anymore. A high obligation modal that indicates a certain obligation for employees to take on more responsibility is found in 17α, have to be able to answer.

19α contains the only explicit affect painful, used by M in this sequence, to convey what she observed in her employees, during this process of change. But the excitement and fear that swept through the organization with this change in hierarchical structure is implicit through clauses 16v to 16vii, with the repetitive use of the word more as emphasis on the importance of the changing responsibilities for employees within the organization. The use of the high obligation modal, have to in 1 7 α indicates not only greater responsibility as previously mentioned, but also a certain pressure for employees to perform when given this new opportunity to expand. The two negatives cannot and not in 18α and 18β, after the use of the high obligation modal in 17α also serves to put defining points of behaviour for the employees and what they were now expected and obliged to do themselves, since there no longer existed a boss to instruct or make decisions on their behalf.

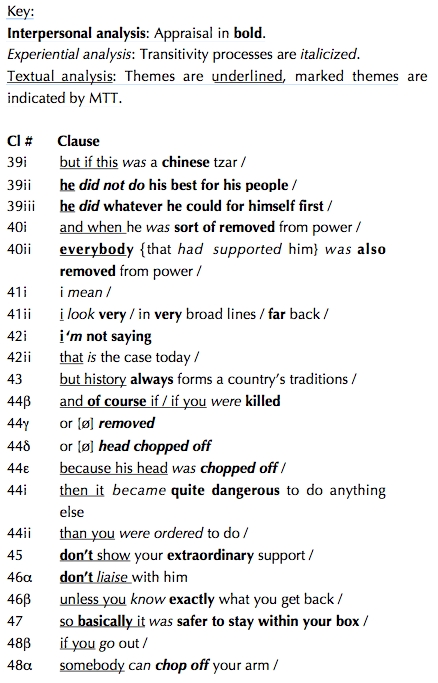

Clauses 39i to 48β also contain clauses where more than one focus amplification is used by M. In these clauses, M passes several judgement statements on what she deems as expected behaviour from a Chinese leader or boss (in 39ii and 39iii). In the clauses below, M begins to explain her point of view of the Chinese socio-cultural history as she understood it, and how it compared to the case of Sweden (in 34δto 37iii). To M, this painful experience of lateralization and decentralization of decision-making for the employees, where they seemed thrust into a situation they have never before experienced, is due to what she sees as a result of a country’s socio-cultural history. For M, there was a greater penalty to pay in the Chinese society if one were to overstep one’s boundaries:

Surrounding Chinese leadership, as M understands it, is a certain fear and negative consequence should the leadership be removed from power, as shown in the use of affect from clauses 40i to 48α, with emotive words that carry a negative connotation of threat, terror and danger. The repetitive use of affective words such as removed (in 40i, 40ii and 44γ), killed (in 48β), chopped off (in 44δ, 44ε and 48α), coupled with the word danger (in 44i) as context, serve to connotate Chinese leadership with danger and a fear for one’s own safety, if not life. The absent agent in these dangerous material processes of punishment from 44β to 48α also serves to create an environment of suspicion for M.

‘Danger’ and ‘fear’ are also contrasted to what is ‘safe’ to do (in 47) and serves to delineate expected employee behaviour under Chinese leadership and authority. This anxiety of power and authority is comparatively unknown or non-existent, in the case of Swedish leadership, as M describes it from clauses 34δ to 37iii.

To M, the history of events with Chinese leadership served to reinforce the message that employees should never step beyond their designated boundaries and that it was safer to stay within the box. Security for employees under Chinese leadership would mean, to do whatever one was ordered or told and to never challenge authority or the power of the leadership.

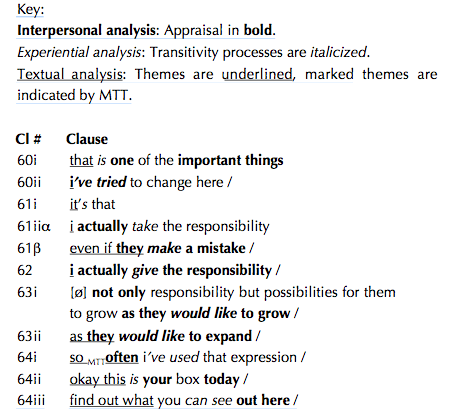

M’s role as a Swedish leader is most prominent in clauses 60i to 64iii where she speaks about her role especially in the process of encouraging her employees to expand their horizon:

M is effectively the agent of the process of change within the organization, from making an assessment of the situation of what type of change is important (in 60i), to having the power to decentralise decision making (in 62), whilst still remaining the leader of the organization and taking on the blame if a mistake is made (in 61iiα and 61β). Several judgements are made, from self- assessment, what she has tried to change (in 60ii) and how she perceives the capacities of her employees and their wants (in 63i and 63ii), as they would like to grow. M distinguishes the difference in her leadership and management style from the Chinese leadership style by using focus amplification in 61iiiα, 61β and 62, with mood adjuncts such as actually in i actually take the responsibility and i actually give the responsibility. And the word mistake in 61β indicates that M possibly expected her employees to encounter difficulties along the way, with the new organization structure; she expected the employees to be incapable of the tasks at hand in the beginning. And unlike the Chinese leadership style that M knows of, mistakes within her organization are allowed to be made, without a surrounding fear or terror of an unreasonable leader. In 63i and 63 ii, M judges her employees and projects their expectations for the future, in terms of their desire to embrace new challenges in their roles in the organization.

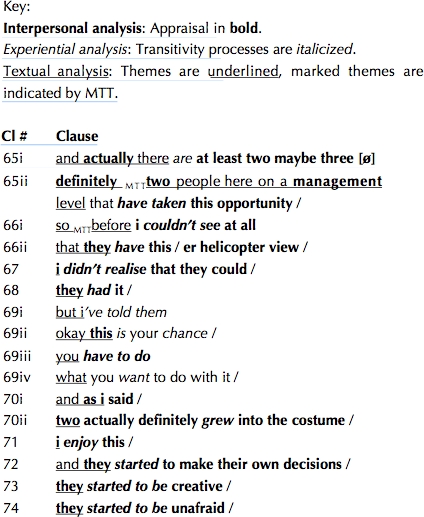

Towards the end of Example 4.k, come some observations and evaluations from M, on the hierarchical changes that have taken place within the organization:

The process of rearranging the hierarchical structure to the organization seemed to have as much impact on M as leader, as on her employees. Using the mood adjuncts actually (in 65i and 70ii) and definitely (in 65ii and 70ii), M reiterates her conviction that her move of lateralization of hierarchy within the organization had positive effects. These positive effects are also emphasized from 70ii to 74, where the various transitivity processes, grew and started to be indicate a material change in behaviour of the employees within the organization. With these changes and the broadened opportunities for employees to take on responsibility, M was also in the position to assess employee capacities, as indicated by the mental processes where she is the Sensor, before i couldn’t see at all (in 66i), i didn’t’ realize that they could (in 67). M would not have previously known the potentials of her employees if she had not implemented these organization changes. M’s judgement and assessment of employee behaviour in clauses 73 and 74 echo her previous judgement on employee behaviour in clauses 28 and 30 and that is, they can [do it].

To conclude this section, the interpersonal, experiential and textual analyses of M’s text example generally profiled an individual who was in a leadership position in an organization. The transitivity processes showed that M took it upon herself to actively make changes not only in the organizational structure of the organization, but she also effected a shift in organizational ideology towards a flatter hierarchy that empowered the employees and encouraged them to be more creative at work. M was ardent in making changes and was clear about her frustrations of the vertical hierarchy within the organization at the beginning. She later found personal satisfaction in seeing her employees grow to a fuller potential under her leadership, towards a more Swedish oriented ideology at work.

5.1.2 A Singapore Chinese point of view: analysis of text Example 4.m

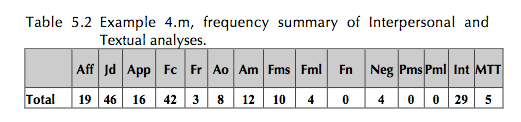

A more detailed text analysis of Example 4.m, with a key to the abbreviations for the SFL framework can be found in Appendix 5ii 4m. A full table containing the three dimensions of analysis that tabulate the number of occurrences for various features, can be found in Appendix 5B, where Table 5B (i) shows the number of features of the interpersonal, experiential and textual analyses, and Table 5B (ii) shows the transitivity processes sorted according to clauses of similar types of processes. Table 5.2 shows the summary of the interpersonal and textual analyses, from Appendix 5B (i). As the interpersonal, experiential and textual analyses are closely intertwined in language and in the making of meaning in context, this section will discuss the various dimensions of analyses simultaneously.

There are altogether, 87 clauses in Example 4.m, and the interpersonal index from Table 5.2 is 164. In G’s text example, judgement, appreciation and the use of adjuncts make up about 50% or half of the interpersonal dimension of the text, indicating that G as an individual is unafraid to express his opinion on events and people around him. The use of amplification (focus and force) make up about 27% of the text and words that indicate affect make up about 11.5% of G’s talk.

The transitivity analysis shows that relational and material processes together form the largest number of process types in text example 4.m, where they make up more than half or 64% of G’s response. 26 out of 87 clauses or about 35% of the clauses are relational processes that reflect G’s point of view about doing business with Europeans and Asians. Relational clauses can be found when G talks about smoother working relations with the Europeans during negotiations, whilst the Asians tend to be less straight forward in their negotiations, for example, “i tell you it was < click of finger > like that / because they were open to me…the locals a r e / are very unreasonable / sometimes unreasonable / …whereas most of the ang mohs are quite / okay i would say quite practical and straight forward”. 25 out of 87 clauses or about 29% are material processes. The material processes (coupled with relational processes) often reflect G as actor, which places G in a position of power, for example, “i got two cases i dealt with european i dealt with the boss number one man” and “i must be personally there to talk to their number one man… and i’d like you to come in / to give you the best terms i have”.

As G uses judgement, appreciation and adjuncts most frequently, the following clauses will be those that contain a high frequency use of these appraisal devices. This is to find out how and in what circumstances G passes judgement when talking and a look at the transitivity processes within these clauses may lend an idea of which participants were involved in the processes.

A first indication that G perhaps works with a vertical organization hierarchy comes from clauses 2 to 3ii, where G places a Finnish guy as his tenant, with the possessive my (in 2). The Finnish national is also leader or boss to a finance manager where G uses the possessive his, to vertically place the Finn in relation to a finance manager within the organization. This vertical hierarchy of ‘who is boss to whom’ is then confirmed by the finance manager who approached G to ask G’s permission to meet with his boss (in 3ii). That hierarchy and rank within the organization is important for G and that it is important for him to have direct contact with the number one man is reiterated several times throughout his talk in 7viii above, and from the rest of Example 4.m in Appendix 5B, clauses 19 and 42. His awareness of either dealing with the boss or wanting to deal directly with the boss, with the words the used as a specific determinative deictic, is also reiterated several times, in clauses 3ii, 14i, 19 (where the boss occurs together with the number one man) and 26i. G’s sensitivity for hierarchy is also indicated in clause 9, when he mentions that some European companies might send somebody senior enough to do business with him.

From clauses 6 to 7v, G begins to compare doing business with the Singaporean Chinese and with the Europeans. In clause 6, the marked theme, we Chinese, we locals, is the focal point for G giving a negative judgement on haggling, which is what G believes Singaporean Chinese people do when negotiating. The word haggle with its connotations also suggests that G feels irritated or hampered with those who quibble with him when negotiating.

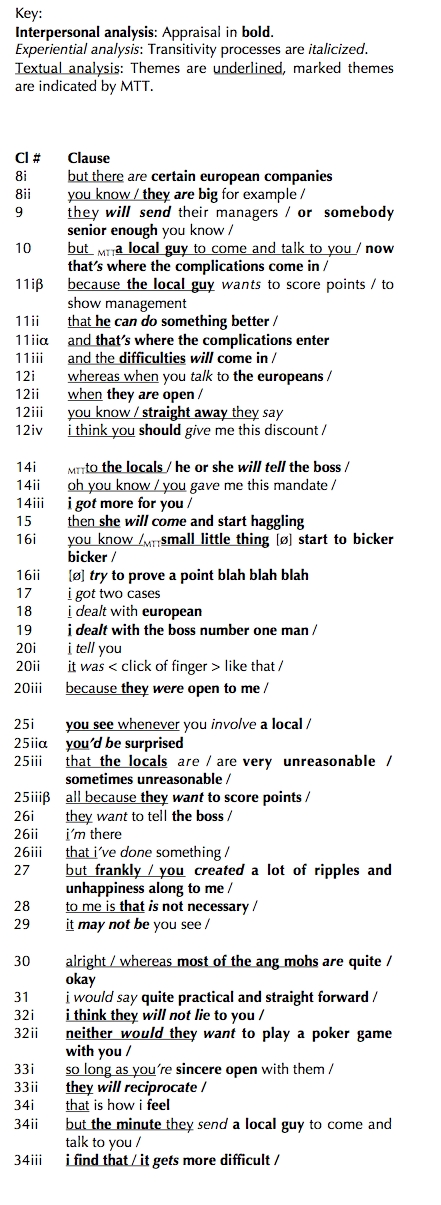

This negative Singaporean Chinese behaviour when negotiating is then contrasted to the European or Scandinavian behaviour in doing businesses, where G sees the Europeans generally as open and straight forward (in 7v). And from clauses 8i to 34iii, G continues to expand intermittently on his point of view of the differences in behaviour when dealing with the Chinese Singaporean and with the Europeans or Scandinavians:

In clauses 10 and 14i, G refers mostly to locals and he does this by putting them in a marked theme position in these clauses. Whether it is a specific demonstrative deictic, the local guy (in 11iβ, 14i, 25iii the locals) or a non-specific deictic, a local (in 10, 25i, 34ii), the focus words and judgements passed by G for the Chinese Singaporean throughout Example 4.m are generally negative in connotation. Affective words from G that imply negative qualities for the Chinese Singaporean include unreasonable (used repetitively in clause 25ii), petty (from clause 16i, small little thing, start to bicker bicker), a person who curries favours (from clause 11iβ, wants to score points, to show management; from clause 11ii, that he can do something better; from clause 14iii, i got more for you; from clause 25iiiβ, all because they want to score points) and a person who needs to brag about their accomplishments (from clause 11ii and clauses 14i to 14iii and 26i to 26iii, which all involve somehow telling the boss what they have achieved). He also credits local negotiators as agents in the material process of creating and bringing unnecessary unhappiness to him in such situations (in clauses 27 and 28).

G not only gives negative judgements but negative appreciation of the situation when having to negotiate with a local Chinese Singaporean. In clause 10, he indicates that he would rather not have European companies send a local guy to negotiate with him, since complications will set in. G also uses a declarative in clause 10, now that’s where the complications come in, to indicate his certainty that the situation will be one that is difficult if a local is sent to negotiate the contract. The words complications and difficulties in appreciation of situation when doing business with the Chinese Singaporean is also used repeatedly in clauses 10, 11iiα for the former and 11iii, 34iii for the latter.

G also seems quite certain when projecting the bickering nature of Chinese Singaporeans, as indicated by the use of finite modals such as will, in he or she will tell the boss (in 14i) and she will come and start haggling (in 15). The finite modal will is also used when G refers to the Europeans and Scandinavians, whom he calls ang mohs, which is a Hokkien term for Caucasians, translated literally to mean, ‘red haired people’. For the Europeans however, G’s finite modals point towards a more positive attitude from G, such as i think they will not lie to you (in 32i) and neither would they want to play a poker game with you (in 32ii) and they will reciprocate (in 33ii).

G’s positive attitude towards the Europeans / Scandinavians is expressed from clause 7v onwards, where he describes them as open (in 7v, 12ii and 20iii). G’s relationship with the Europeans seems to be a reciprocal one, on equal footing since in clause 33i, he mentions that one should also be sincere open with them in order for them to do the same. Apart from the word open, other affective words that G associates with the Europeans are efficient and direct (with the words straight away in clauses 21iii, 20ii), reasonable (as opposed to the locals being unreasonable in 25iii), practical and straight forward (in 31), honest (in 32i and 32ii), reciprocative (in 33ii) and easy to deal with (in 34iii, and as opposed to the local who is generally difficult and complicated).

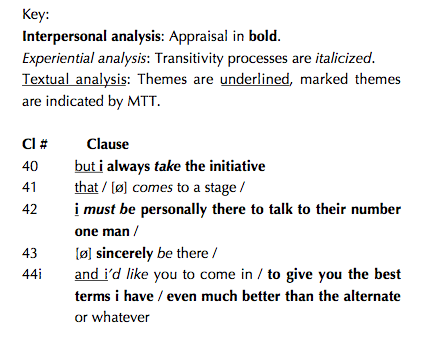

In clauses 40 to 44i, G concludes his talk around the topic of hierarchy:

G’s awareness of dealing with the number one man were conveyed previously in clauses 18 and 19, with G as agent in the material process dealt in i dealt with European, i dealt with the boss number one man. Other material processes where G is agent or actor can be found in the above clauses from 40 to 44i, where G takes it upon himself with an indication of high obligation, to be there for his clients. This is indicated with the use of the mood adjunct always in i always take the initiative (in 40) and the high obligation finite modal must in i must personally be there to talk to their number one man (in 42, reiterated in 43 with sincerely be there). To a high degree, G feels most comfortable working with top leaders and persons who can make decisions and he feels that such situations will enable him and give him the opportunity he needs to give his best (in 44i).

To conclude this section on SFL analysis, the transitivity analysis showed G to be an individual in power, who saw himself as “the number one man”. G had the power to make final decisions on negotiations and as such, he often preferred dealing with others who held similar decision-making powers or those who occupied similar hierarchic positions within the organization. G often saw Europeans as easier to deal with and in fact, preferred to deal with Europeans compared to Asians, since he understood that most Asians sent by organizations to negotiate with him were not of equal standing, meaning that they were not in the position to make the final decision themselves. The interpersonal analysis showed that G felt highly encouraged by the “open” nature of the Europeans and he preferred that open approach compared to the Asian attitude in negotiatons. He was strongly critical about the difficulties that often arose out of negotiations with Asians. On his part, he possessed a strong sense of responsibility and obligation to be available for his clients when his clients needed him.

5.1.3 Words in context analysis

Words in context analysis for the word ‘boss’

The word boss seemed to surface frequently in both text Examples 4.k and 4.m when both M and G were speaking of hierarchy within the organization. While the linguistic framework used in the previous sections allowed for an in-depth view into the individual’s attitudes and point of view on the topic of hierarchy within organizations, a look at the word boss as used in context by the respondents will allow for a general cross-sectional view of how the word has been used by all participants in the study. The concordance software Textstat has been used to help situate the word boss in its context, the context is then cut and pasted into an Excel sheet (Appendix 5C) for further analysis.

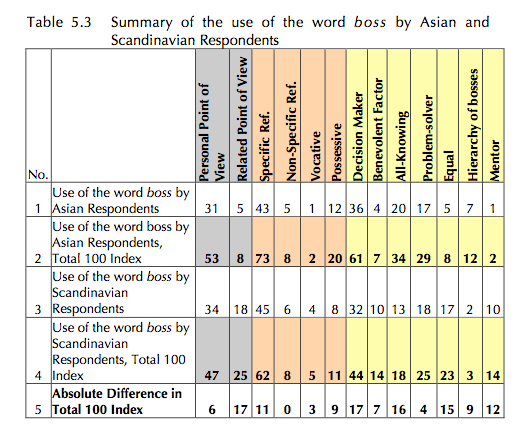

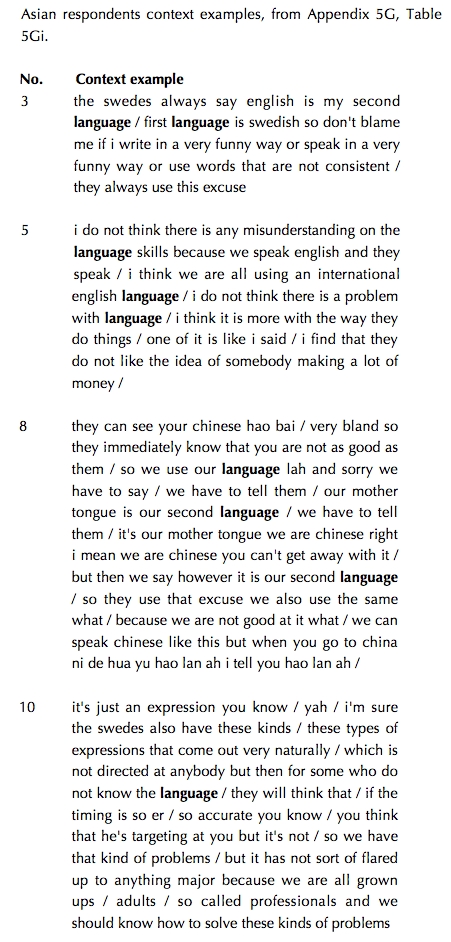

There are altogether 132 instances of use of the word boss with 59 instances (45%) by the Asian respondents and 73 (55%) instances by the Scandinavian respondents. A detailed log of the use of the word boss in context by all respondents can be found in Appendix 5C, and Table 5.3 below shows a summary of the different nuances of meaning in the use of the word boss as used in context by both groups of respondents, along varying planes of lexico-grammatical meaning. The meanings of the word boss as reflected in Table 5.3 is corpus based and is derived from the use of the word in context as shown in Appendix 5C.

The columns from left to right, correspond to whether the word boss was used to reflect a personal point of view, or if the respondent was relating someone else’s point of view, if the word boss was used as a specific or non-specific reference, as a vocative or used together with a possessive pronoun, as in the phrase “my boss”. The word boss is also used in various semantic meanings such as referring to a decision-maker, someone who is benevolent, all-knowing, and a problem-solver. In relation to the self, the boss can also be viewed as an equal or a mentor and a boss can also be viewed in a vertical hierarchy of bosses.

As there is an unequal number of respondents in both groups, with 23 Scandinavian respondents and 10 Asian respondents, a Total 100 Index is calculated to enable the two groups of respondents to be compared on an equal basis. The Total 100 Index numbers for the manner in which each group uses the word boss is reflected in rows 2 and 4 in Table 5.3. In row 5 of Table 5.3, the absolute difference shows the differences in usage of the word boss between the two groups, the red numbers show that the Scandinavians had used the word in that particular manner more than the Asians.

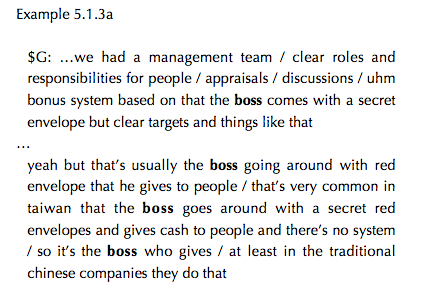

As mentioned briefly above, the column indicating “Personal Point of View”, indicates whether the respondents voiced their own opinions and the column, “Related Point of View” indicates if they had narrated an experience concerning the concept of boss and mentioned ideas / opinions which could in fact be contrary to their own beliefs and definitions of what a boss is. The numbers in Table 5.3 reflect that the Scandinavian respondents related stories of their experiences in which the word boss was used, more than the Asian respondents. This implies that the high number on the Benevolent Factor, 14, could well be due to the Scandinavians relating how they understood their Asian counterparts to view the role of bosses, rather than what they themselves perceive on the role of bosses. As an example of the difference between the columns “Personal Point of View” and “Related Point of View”, the text example below with Swedish respondent (Swe)G relates his experiences in Taiwan on the concept of boss. It is an example of how it is not (Swe)G who had voiced his personal point of view of how a boss should behave towards employees but he had rather narrated an understanding of an experience he has had in Taiwan of how bosses behave and are perhaps expected to behave by employees:

While (Swe)G tells of how he understands that the boss goes around with a red envelope with cash to certain people within the organization, it is also understood that he as a boss does not behave in the same manner. In this instance, occurrences of the word boss would appear under the second column, as a “Related Point of View”. Such instances will lend insight into the Asian management style, as observed by the Scandinavian respondents.

(Swe)G’s narration of how the boss personally takes care of the employees’ bonuses by going around the office without “a system”, distributing “secret red envelopes” is also an illustration of Hofstede’s (1984) idea of how the employees are more dependent on the superiors to be benevolent in act and deed, reflecting the implicit “family” model of the organization where a patriarch or a matriarch is in charge. The “giving boss” can be traced by (Swe)G’s use of lexes in Example 5.1.3a:

the boss comes with…the boss going around with…gives to people…the boss goes around with…gives cash to people…the boss…gives…they do that

The word usually in that’s usually the boss going around with, implies that the procedure is somewhat of a tradition, having been in place for a long time.

The four columns in Table 5.3, labelled “Specific Reference”, “Non-specific reference”, “Vocative” and “Possessive” illustrate how the word b o s s is used in a paradigmatic construction, for example, co-occurring with specific deictic determiners such as the and this, or together with possessive pronouns such as my boss and his boss. Boss is also used as a vocative in Singapore, as in someone addressing a superior as boss, such as No.36 in the Asian respondent group from Appendix 5C, Table 5Ci:

boss / our competitors are like this and this you know and we need to drop the price

And No.4 from the Scandinavian group of respondents from Appendix 5C, Table 5Cii:

no / boss he went out / why we have an appointment

In terms of absolute differences, the two nuances of meaning with the greatest relative distance of 17 between the two groups show that many Scandinavians used the word boss in a ‘related point of view’ compared to the Asian respondent, who tended to use the word in expressing a personal point of view. Asians were also twice as likely to use the word boss together with a specific deictic determiner, such as the boss, as shown by the 43 instances between 10 Asian respondents, compared to the 45 instances between 23 Scandinavian respondents.

For the Asian respondents, the word boss seems to carry an inherent meaning of authority and “power over”. The use of the words my boss, which is a common occurrence in the manner in which the Asians use the word, inherently carries the meaning that the sayer is in a lower rank in the organizational hierarchy than the person who is referred to as the boss, such as i report to my boss in hong kong / who is overall in charge / and my boss once told me / you know / after tax i earn less than a lot of people (from Appendix 5C, Table 5Ci:6 and 54 respectively).

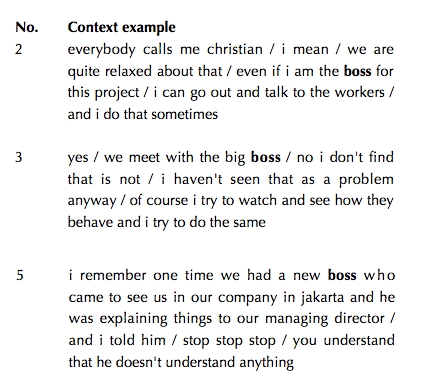

While both groups saw the boss as a problem-solver, as indicated by a relatively small absolute difference, the inherent authority that bosses carry meant that the Asian respondents tended to view the boss as someone who was trusted in making all decisions (indicated by an absolute difference of 17 towards the Asian respondents) and that the boss was a person who was all-knowing (indicated by an absolute difference of 16 towards the Asian respondents). For the Asians, bosses were unlikely to be an equal and less likely to be a mentor than for the Scandinavians. This is indicated by an absolute difference of 15 and 12 for Scandinavians viewing their bosses as equals and as mentors, compared to the Asians index of 8 and 2 respectively. Examples of bosses as equals and / or mentors from Appendix 5C, Table 5Cii include:

From the above examples, it seems that though there is a hierarchy in place within the organizations in Singapore, the Scandinavians seem more relaxed about the vertical hierarchy, preferring to be called by their first names and talking to workers further away from top management level.

That the Asian respondents tended to view the existence of a vertical hierarchy within the organization is also indicated by they ways they viewed their bosses placed in a vertical hierarchy as well, meaning that a boss is differentiated from a big boss and that a boss is also differentiated from the boss, the latter being more specific in relation to the individual and thus assumed to have certain dominative power over the individual.

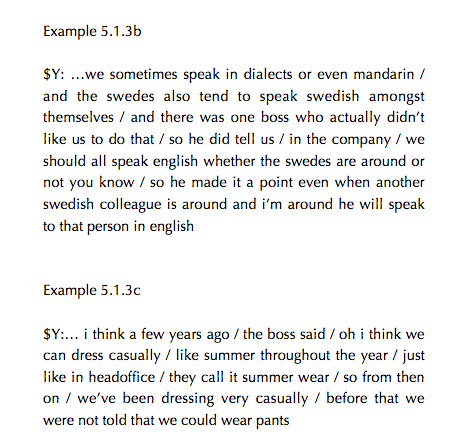

In some Asian respondents’ point of view, the role of the boss extends beyond organizational matters to include social decisions including the language spoken within the organization, office dress codes and menu choices for a company dinner and dance. One could say that the trust Asians tend to have in their bosses extends to a wider social circle. Viewing their bosses as an all-knowing and benevolent patriarch, the Asians trust their bosses to make right, appropriate and favourable decisions on matters even outside organizational boundaries. This point of view is not shared by the Scandinavians.

Examples 5.1.3b and 5.1.3c show two text examples for the word boss from a Singaporean Chinese respondent Y, who was speaking on the topics of language in the office and the organizational dress code. Y has been working in a Swedish managed organization in Singapore for 25 years at the time of the interview:

The boss in the above example is placed in the role of agent, one who not only has the power to do things but to effect change within the organization. The boss is given the active role of decision maker who gives instructions, in Y’s clausal constructions. Agency is in bold and the material processes in italics:

he didn’t like us to do that

he did tell us in the company

he made it a point even when…

he will speak to that person in english

the boss said …

Even in passive construction, the boss’s authority still comes through in the form of a given order:

we were told [ellipse] that we could wear pants

The various roles that Y sub-consciously attributes to ‘the boss’ suggests the role of the boss as the sayer who instructs and the doer that implements, that he does not like x implies that the rest of the organization should follow his wishes, we should all speak english and so from then on / we’ve been dressing very casually. The boss is placed as the individual who wields power over employees, advising on how employees should speak and what they should wear to work, we were told [ellipse i.e. by the boss/management] that we could wear pants.

As the words in context analysis has shown for the word boss, the Asians and Scandinavians understand the concept of ‘what is a boss’ quite differently. The Swedes for example prefer to be in contact with the employees on a first name basis, whereas the Singaporean Chinese who prefer to perpetuate a vertical hierarchy prefer to use the word as a vocative, calling their bosses, ‘boss’ as a sign of respect. This difference in point of view on what role the boss plays, how benevolent they are expected to be and the extent of their influence within the organization may result in misunderstandings and frustrations on both sides, in part due to differing cultural values.

Words in context analysis for the word ‘hierarchy’ and its variations

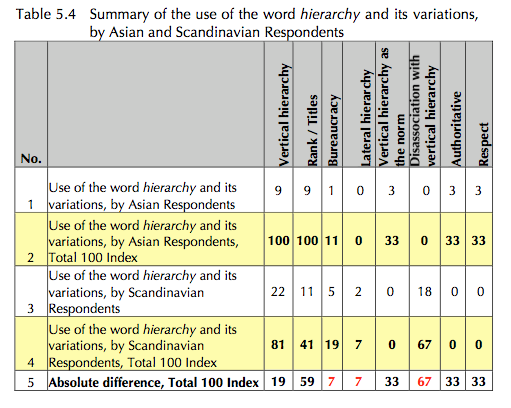

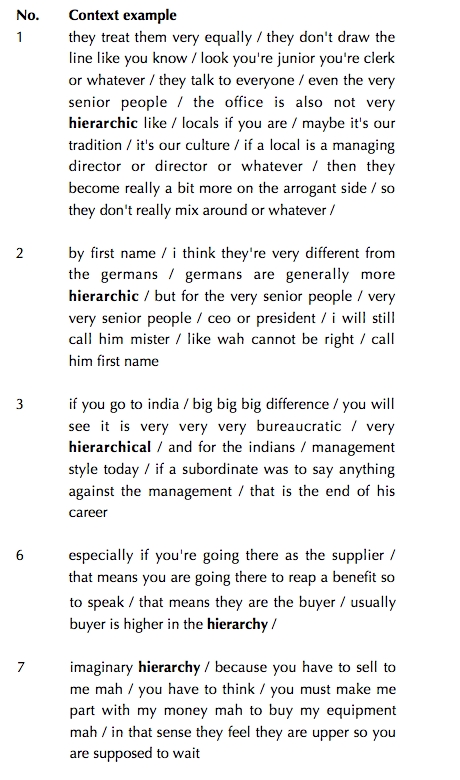

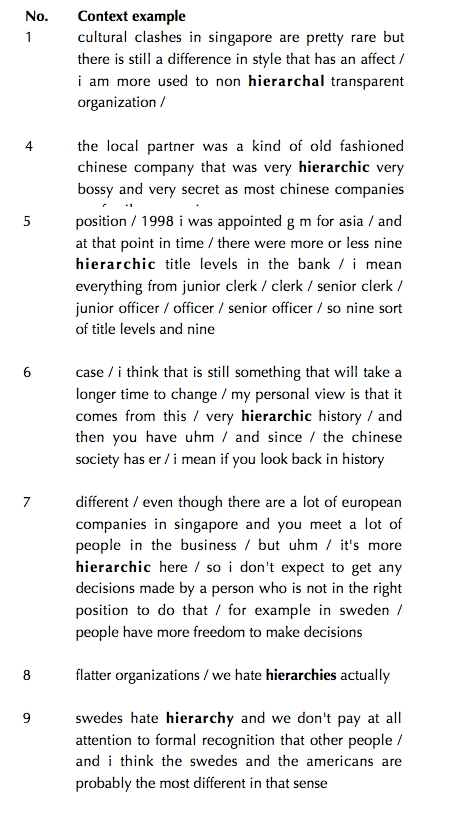

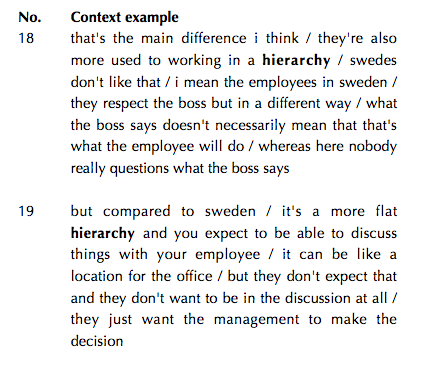

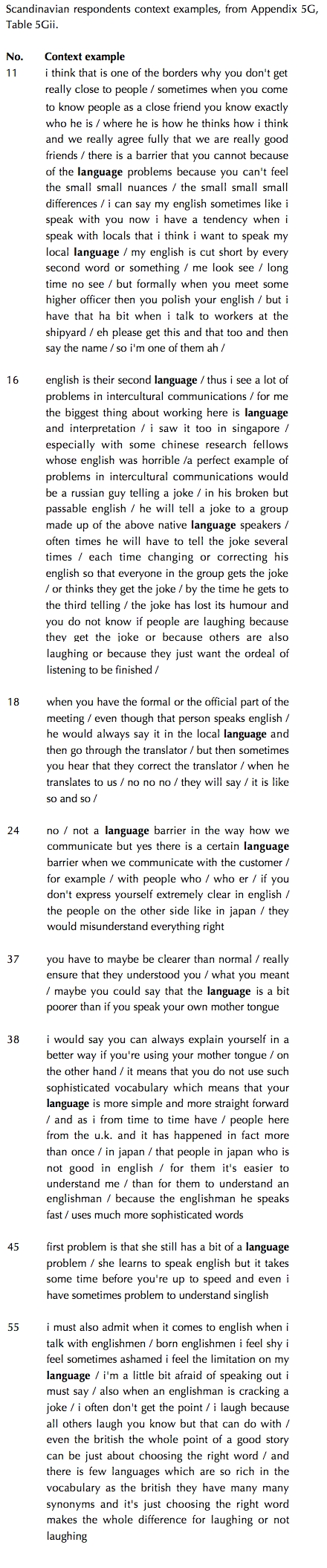

Although the word hierarchy was not used by G in Example 4.m (the words boss and number one man were used in reference to hierarchy), and it was not explicitly mentioned much by M in Example 4.k (the words hierarchic title levels and levels were used, in Example 4.k), a look via TextStat at the transcribed data / corpus for the word hierarchy and its variants such as hierarchic, hierarchies and hierarchal retrieved 33 instances of use of those words altogether with 9 (27%) instances of use by the Asian respondents and 24 (73%) instances of use by the Scandinavian respondents. A detailed log of the use of the word hierarchy and its variants in context can be found in Appendix 5D, where Table 5Di shows the instances of use by the Asian respondents and Table 5Dii shows the instances of use by the Scandinavian respondents. Table 5.4 below shows a summary of the instances of use and the nuances of meaning of the words as used by both groups of respondents. The 100 Index allows for both groups of respondents to be compared on an equal basis. The absolute difference in row 5 of Table 5.4 shows to what extent the two groups of respondents have used the words differently, the red numbers indicating a trend towards greater use of the words by the Scandinavians.

The absolute differences show that the two groups of respondents tended to view hierarchy in a slightly different manner of meanings. All of the Asian respondents showed an awareness of the existence of vertical hierarchy and used the words in a context of talking about or explaining a vertical hierarchy. Some of them spoke at the same time, of ranks and titles (as indicated by the high absolute difference of 59 for example, for rank / titles). Some examples from Appendix 5D, Table 5Di include:

n 6 and 7 above, it seems that the concept of vertical hierarchy is mandatory for the respondents, one that pervades organization life, where hierarchy exists even in a buyer-seller relation, so that an imaginary hierarchy exists and that the buyer has the advantage over the seller in the sense of whether to purchase or not.

While the Scandinavians also tended to use the word hierarchy to refer to vertical hierarchies, they often expressed their dislike or disassociation from vertical hierarchy in the same context. Disassociation or dislike of vertical hierarchy is an aspect of use that apparently does not exist for the Asian respondents. This is shown with an absolute difference of 67 in Table 5.4, row 5 in favour of the Scandinavians and index 0 for the Asians. Some examples of Scandinavians using the words in a context of disassociation, from Appendix 5D, Table 5Dii include:

Examples 5 and 6 have been seen previously from Example 4.k where M speaks of her discomfort with too many hierarchic levels within the organization, which led to her making changes to the hierarchic structure within the organization, to what she recognized as more Swedish. In other examples above, the concept of hierarchy for the Scandinavians is surrounded by negative connotations and points of view. Hierarchy for the Scandinavian respondents is associated with non-transparency, secrecy (in examples 1 and 4), bossiness (in example 4) and lack of general freedom to make decisions (in example 7). In examples 8 and 9, the word hate co-occurs with hierarchy, where the respondents explicitly state that they hate hierarchies.

In example 8 above, the concept of flatter organizations with a lateral hierarchy is brought up, where in Table 5.4, row 5, the absolute difference 7 also shows that the concept of a lateral hierarchy exists for the Scandinavians but not for the Asians. Examples 18 and 19 from Appendix 5D, Table 5Dii show some Scandinavians speaking on lateral hierarchy, also known as ‘flat’ hierarchy:

5.1.4 Discussion and Conclusion: Profiling the Asian and Scandinavian point of view on Hierarchy

‘The boss is the boss’ vs the boss as mentor

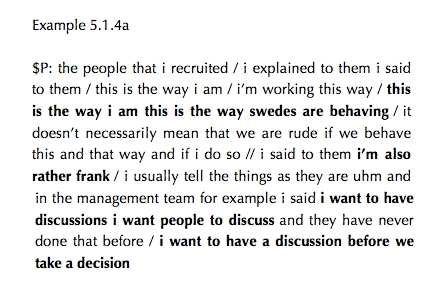

The words in context analysis of the words boss and hierarchy (with its variations) showed that both groups of respondents used and understood the words in a manner that was different from each other. The words in context analysis for the word boss indicated that the Asians saw bosses in a more authoritarian dimension, as someone who was all-knowing and who had the prerogative, an almost exclusive right in making decisions. This right to making decisions for the entire organization was what was reflected in the ‘employee handbook’ that M talked about in Example 4.k, where she felt compelled to make a change in the employee handbook for the organization. The Asian respondents also had a concept of a boss that was benevolent, one who would take care of the employees in a paternal manner. This form of paternalistic leadership style seemed to have been noted by the Scandinavians, though they do not themselves partake or share such a concept. Generally, the Scandinavians would see bosses as mentors and advisors but not necessarily the decision- makers in all things pertaining to the organization. Bosses were there for open dialogue and for conferencing with, as a person who would help in the brainstorming process, though not necessarily the problem-solver, as one Swedish leader puts it to his employees, where his ideas on his leadership are in bold:

P’s emphasis was on open discussions and having discussions before taking a decision. He encouraged information sharing and open talk in his leadership style and he encouraged people being straightforward when talking with him.

How each group of respondents used the word boss was also reflected in their understanding and use of the word hierarchy, where generally, the Scandinavians as a group seemed to emphasize a disassociation and a steering away from the use of vertical hierarchy within organizations. Vertical hierarchy within the organization for the Scandinavians seemed to pose more barriers in terms of transparency, openness and smooth operations. For the Scandinavians, vertical hierarchy is not given but something to be challenged, questioned and possibly re- structured.

Vertical hierarchy vs lateral hierarchy

On the individual level, the text analyses of Examples 4.k and 4.m, indicated that both M and G had different points of view when it came to hierarchy. For M, it was a discomforting fact that there existed many levels of hierarchy within the organization when she took over as general manager in 1998. To M, seniority and titles were second to one’s responsibility at the office and responsibility came with the ability to step beyond one’s personal boundaries and make decisions on behalf of the organization. This meant that decentralizing decision-making and flattening the hierarchy within the organization was crucial for what M wanted to achieve both in terms of organizational structure and creativity, initiative-taking on the part of the employees within the organization. For M, job satisfaction is as much derived from enabling and empowering her employees as steering the organization to success. The empowering of employees was a main theme in Jan Carlzon’s (1985) book on managing SAS to success.

For Singaporean Chinese G, who is CEO of the organization however, the concept of hierarchy, ranks and titles runs deep and is implicit in his culture. The idea of decentralized decision-making is not a central or perhaps even known concept for G. If G is aware of lateral hierarchy, it seems to be a concept that is hardly entertained or accepted. He repeatedly mentions how important it is for him to deal directly with other leaders of organizations, or the number one man. He deems it an unnecessary waste of time if organizations were to send someone other than the leader of the organization, regardless if that person had the power to make decisions, since that person, if he / she were a local, would likely end up bargaining for a better deal. It matters to G that the person with whom he conducts business, is of the same seniority and rank as he, within the corresponding organization.

It was also noted that Scandinavian respondents seemed to disassociate themselves from the concept of vertical hierarchy, deeming vertical hierarchies to be cumbersome and inflexible, hindering a job done rather than facilitating efficiency within the organization.

5.2 Assimilation / Integration

As mentioned in Chapter 4, the terms ‘assimilation’ and ‘integration’ were put together as a single topic for the purposes of coding the data even thought the words have a slight variation in meaning. Assimilation refers to a non-dominant group giving up their socio-cultural heritage in order to be absorbed completely by the dominant culture (Albe and Nee, 1997; Petersson, 2006) and integration refers to newer socio-cultural ethnicities becoming part of the dominant culture, with recognized differences and change on the part of both dominant and non-dominant group (Goldmann, Pedersen and ∅sterud, 1997; Petersson 2006).

As both assimilation and integration are processes that need a longitudinal study to ensure if the processes are taking place, the purpose of the analysis in the following sections, which reflects a synchronic investigation, is to uncover how the respondents have talked about these concepts, how they have used the words in context and consequently, to investigate if the respondents report having made any assimilative and / or integrative efforts when working together. Both assimilation and integration efforts are viewed in this study as cooperative efforts from the Scandinavians and Asians, meaning what each group does in order to cooperate with the Other.

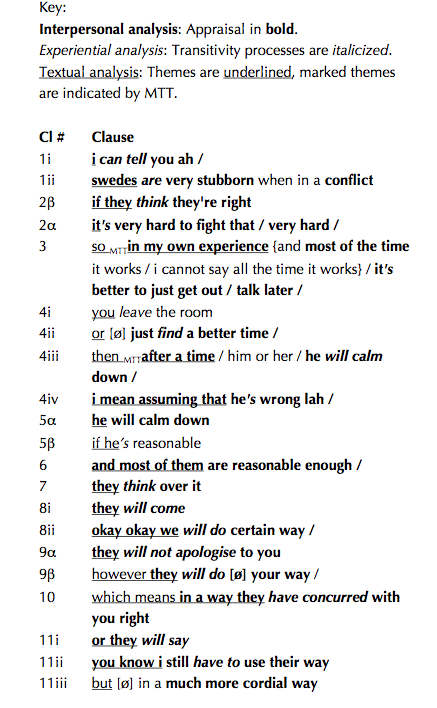

5.2.1 A Scandinavian point of view: analysis of text Example 4.n

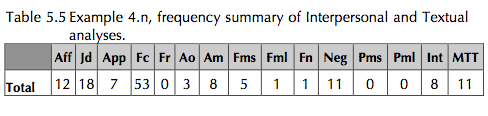

A more detailed SFL text analysis of Example 4.n can be found in Appendix 5iii 4n together with the key to the use of abbreviations. A full table containing the three dimensions of analysis that tabulate the number of occurrences for various features, can be found in Appendix 5E, Table 5E(i). Table 5.5 shows the summary of the interpersonal and textual analyses from Appendix 5E(i). Table 5E(ii) in Appendix 5E shows the transitivity processes grouped according to similar process types. The following discussion on the various strands of interpersonal, experiential and textual analyses will take place simultaneously.

There are altogether 59 clauses in Example 4.n, with the interpersonal columns (all columns in Table 5.5 except the last two textual analysis numbers columns of ‘Int’ and ‘MTT’), adding to a total of 119. Table 5.5 shows that a median 45% on the interpersonal dimension of B’s talk is amplification (focus and force). Judgement, appreciation and both comment and mood adjuncts make up about 30% of B’s talk. Words that indicate affect make up about 10% of B’s talk, which is a similar percentage of affect in B’s language use as with previous respondents. At the time of the interview (in 2004), B had been living in Asia for about 26 years, of which 13 years were spent living in Singapore.

The transitivity analysis in Appendix 5E, Table 5E (ii) shows that relational processes make up the greatest number of process types, with 20 out of 59 clauses or 34% of the text being relational processes. These process types usually state and describe B’s situation of being in Singapore, such as “i’m here for my business”. It helps B to position himself in relation to the locals, “we are not of the same people we are not brought up the same we don’t have the same interests”. B’s distinguishing of himself from the locals is also seen in the next largest group of process type, the mental processes. There are 16 instances (or 27%) of mental processes, in which B is sensor in these processes and he tells how he feels about things, “i feel very much swedish / not less swedish no”, “i love to go back for the summer holiday” and “i like scuba diving / search for shipwreck that kind of thing”. In the material processes, which account for 15 instances or 25% of the text, one finds B in a position of power and actor. B is actor and agent in material processes such as “i let my local staff handle all that administration”, “our client customer contacts / i let my locals do it”. B is also part of the in-group of ‘we’ within the organization, those who run the organization, where he is also seen as actor in the material process of selling products, “we are selling to shipyards and ship owners”. The 3 existential process types in this example seem to all be connected with B’s feeling of isolation, when he says, “…but there are certain er limit”, “…and there is my limit to get into this society”, where for B there exists a rather concrete limit of how integrated he can be, in the local society.

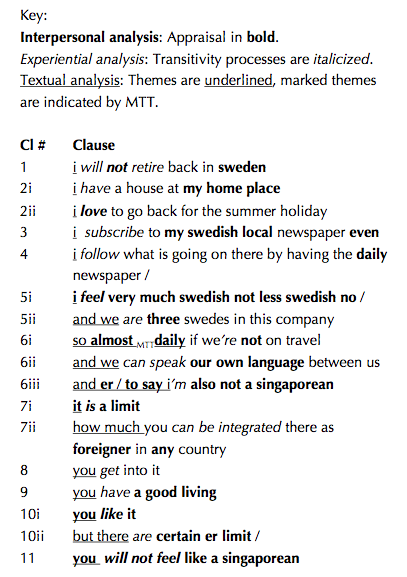

Although B does not explicitly use the word assimilation, he does mention integration in clause 7ii. B’s sense of feeling ‘at home’ in Singapore or in Sweden is addressed from the opening line of Example 4.n:

Although B does not see himself retiring in Sweden, clauses 1 to 11 shows B identifying Sweden as his home and he as Swedish. B for example, often uses the possessive pronouns my and our when talking about things related to Sweden, such as my home place (in 2i), my Swedish local newspaper (in 3) and our own language (in 6ii) to refer to the Swedish language. Affective words such as love (in 2ii), feel very much (in 5i) and focus words such as daily to refer to daily newspaper (in 4) and speaking the Swedish language daily (in 6i) show B to feel strongly about his Swedish roots, i feel very much swedish not less swedish no (in 5i).

B’s point of view where he does not identify with the Singapore society, is strongly put across when he uses the negative polar not after the focus word also, rendering the clause i’m also not a singaporean (in 6iii) and when he uses the finite modal coupled with the negative polar, will not, in clause 11, you will not feel like a Singaporean. Appreciation words used on his situation in Singapore, such as limit in it is a limit (in 7i) and there are certain er limit (in 10ii), also show B to be highly conscious that he is a foreigner. Clause 7ii also implies that B continues to feel as a foreigner even after spending more than 20 years in Asia, where he distances himself or distinguishes himself from feeling Singaporean (in 5i, 6iii and 11).

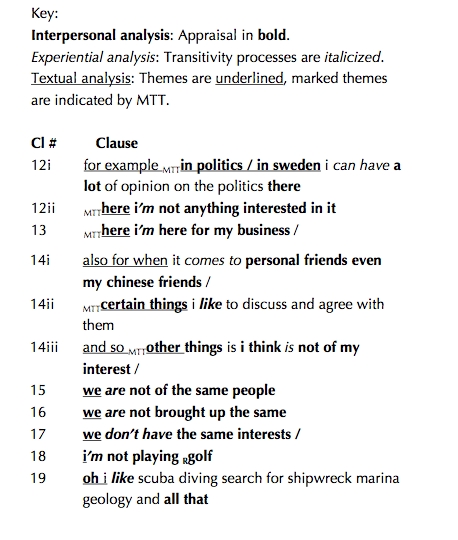

The following clauses, from 12 to 19 from B, contain a high concentration of marked themes, judgements and the use of the negative polar, not:

The marked themes indicate that B orientates himself spatially between groups that he feels he belongs to. This can be found in terms of geographic references such as in Sweden…there (in 12i), here in reference to Singapore (in 31) or if it’s a mental reference of interests for B, such as here in reference to an interest in politics in Singapore (in 12ii), certain things (in 14ii) and other things (14iii). The clauses 12i to 19 are also generally relational clauses, such as i am and we are, which indicate that B is speaking about how things are, their circumstances and attributes. B demonstrates knowledge of his boundaries of interest and that he is conscious of not belonging to the Singapore society, that he is only in Singapore for his business (in 13). The cluster of judgement clauses from 15 to 19 set B apart from his Singaporean social circle of friends, with the negative polars not (in 15 and 16) and finite negative don’t (in 17) emphasizing differences. The judgement B puts forth in clause 18, i’m not playing golf is culture specific since golf seems to be a ‘business sport’ of sorts and indicative of one’s social status in Asian societies, especially Singapore, so that when B says that he does not play golf, he is also saying that he does not socialize in the same network circles. Golf as a land sport is also contrasted to the sea sports that B prefers such as scuba diving, diving for shipwreck and marine geology (in 19), which are activities that can be identified as more west coast Swedish activities during the summer.

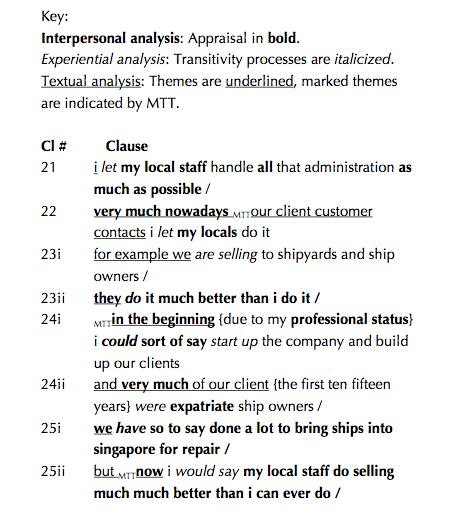

In clauses 21 to 25ii, B explains how his local business is run in Singapore:

The clauses above are generally material clauses, indicating B as the agent who allows for the locals (actors) to proceed with doing business, i let my local staff handle all that administration (in 21) and i let my locals do it (in 22). The two marked themes in the beginning (in 24i) and now (in 25ii) serve as points of contrast for B, where it was he who did most of the business in the local scene at first. His connecting point to the local scene, apart from his professional status (focus words in 24i), was still, his expatriate status, being able to connect with expatriate (a focus word in 24ii) ship owners. Clauses 21 to 25ii generally emphasize the importance of the role of local employees in B’s business venture and what is happening now (marked theme in 25ii), where B judges his local employees to do better business these days than he, they do it much better (23iii) and my local staff do selling much much better (25ii).

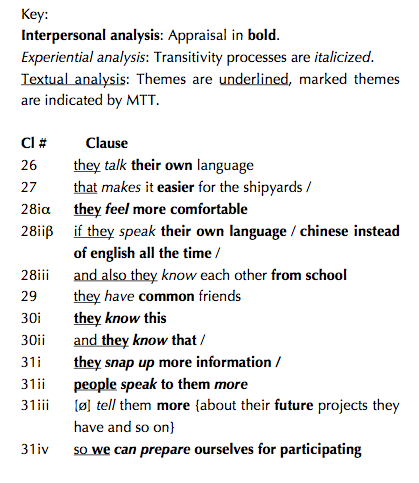

From clauses 26 to 31iv, B tells in his view, what he deems to be the key to his local staff being able to do business better than he is able to these days:

Of the 12 clauses above, 5 are mental clauses that have they or ‘the locals’ as sensers of the phenomenon such as feel (in 28iα), know (in 28iii, 30i, 30ii) and snap up (in 31i). These mental process types are typically associated with the locals having knowledge of the network and the knowledge to network. Other dominant processes in the clauses are verbal processes, which also forms part of the processes of networking and business building, talk (in 26), speak (in 28iiβ and 31ii) and tell (in 31iii) where it goes on between B’s local employees and their clients, so that clients divulge future (a focus word) project information. B also views that the binding factor for relationships is sharing a common language, found in clause 28iiβ. A common language feature is also highlighted previously in clause 6ii, where B mentions that he speaks Swedish with his Swedish colleagues.

Focus words such as from school and common friends in clauses 28iii and 29 show a background context in which relationships are built, it also indicates a context of long-term relationship building, a history of connecting with the right persons. Relationship building and the concept of networking with friends is elaborated by B, in clauses 32 to 36:

The marked theme, not only language (in 32) serves as a point of departure for B to launch another point of view on the concept of networking and the feeling of belonging, that of friendship. Dominant in clauses 32 to 36 are focus words and judgements from B that continue to define relationships and friendships, where he again mentions my limit to get into this society (in 33i, previously mentioned in clauses 7i and 10ii). For B, friendships formed in Singapore are not as deep as those formed back in Sweden, his home (in 34v). Judgements about trust and bonding are indicated in clauses 34v and 34vi, where he feels he has a deeper bond with his own childhood friend or those whom you did your military service together i.e. those with whom you can trust your life.

Through B’s talk, there are several clauses that indicate that life is good in Asia, such as i will not retire back in sweden (in 1), you have a good living (in 9), you have many friends you can call friend and they are good friend (in 34i, 34ii and 34iii). B even tries to soften the focus using a little bit and soften the force of the feeling of not belonging with a tentative hedge, in a way in clause 35, in a way, you fell a little bit outside. But the emphasis words in declarative, you do in clause 36 echoes clause 11, which contains a high certainly modal in the negative, you will not feel like a singaporean, still drive home the point that B nonetheless does not feel all that integrated with the Singapore society.

To conclude this section, the SFL analysis showed B’s affection for Sweden and being Sweden, even though he does not see himself retiring in Sweden. After 26 years in Singapore and Asia, B still feels non-integrated with the local society and the transitivity analysis indicated that he felt ‘more Swedish’ than local and when it came to doing business. B also often preferred to let his local staff do the negotiations, citing a language barrier and networking barrier on his part, compared to his local staff who had better local networks.

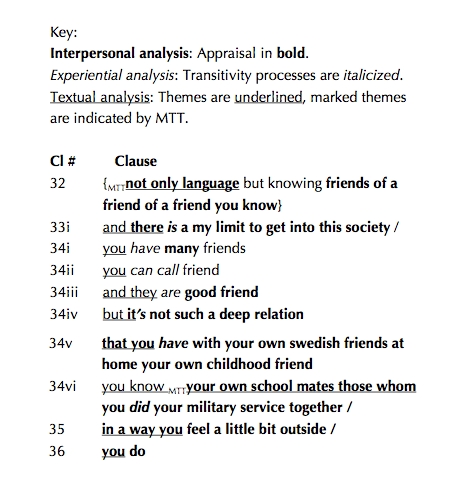

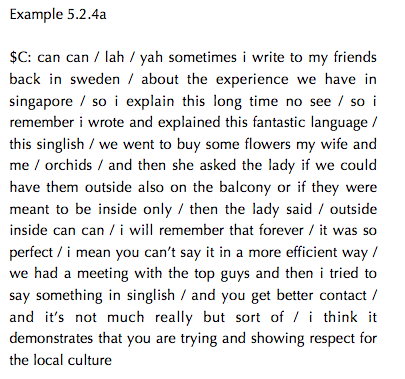

5.2.2 An Asian point of view: analysis of text Example 4.p

As the SFL framework of analysis is extensive, a more detailed text analysis with the SFL framework of Example 4.p can be found in Appendix 5iv 4p. A full table containing the three dimensions of analysis that tabulate the number of occurrences for various features, can be found in Appendix 5F with Table 5F(i) showing the interpersonal, experiential and textual analyses numbers and Table 5F(ii) showing the transitivity analysis sorted according to similar process types. Table 5.6 below shows the summary of the interpersonal and textual analyses from Appendix 5F.

There are 99 clauses in Example 4.p with an interpersonal total of 223. Table 5.6 shows that most of P’s text example, about 41% of the interpersonal dimension of language use is made up of judgement, appreciation and both comment and mood adjuncts. 39% of the interpersonal dimension of P’s talk is the use of amplification (focus and force). Affect in P’s language use is relatively low compared to the other three respondents, with about 0.05% use of affect.

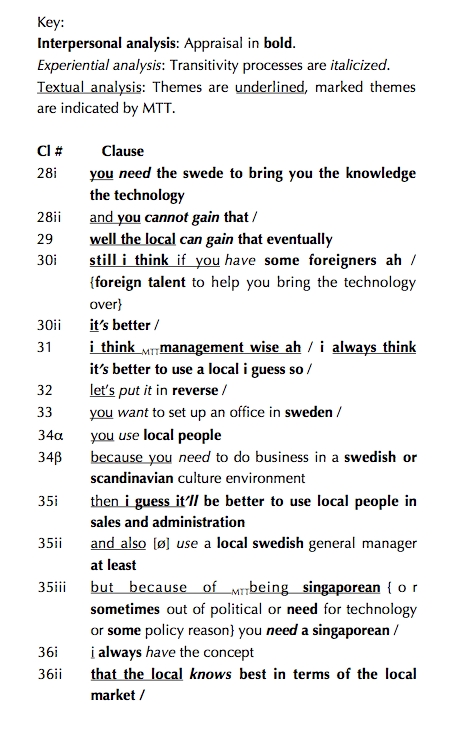

The transitivity analysis in Appendix 5F, Table 5F (ii) shows that there are almost equal numbers of relational processes and mental processes with 32 instances or 32% relational processes and 31 instances or 31% mental processes in text example 4.p. The relational processes show P’s point of view of his working situation, “in the corporate life it’s like this“ and it gives insight to how P views his Scandinavian colleagues, for example, “swedes are very stubborn “ and “ [the] good thing about swedes is that if they think about it they might come to their senses and settle it once and for all /” and how he views relationships with Asians in times of conflict, “long term relationships are bound to be affected / once you have a quarrel with another asian”. A clustering of mental processes can be found towards the end of text example 4.p when P talks about whether Swedes or Asians should run the Asian subsidiary of the organization. In these mental processes, P projects the Other as senser of the mental processes, “they will want to put one of their own there…but like i said lah some they think they want to try their way and after awhile you see whether it works or not / that’s what i think so lah / but there are some swedes who prefer to use their own people to run certain markets”.

The 21 instances or 21% of material processes shows P’s way of dealing with colleagues during times of conflict or disagreement, with either a general you as actor or P refers to himself as actor of the material process, “you leave the room or just find a better time /”. It also reflects the power struggle between colleagues when doing things and who has right of way, “they will do your way / which means in a way they have concurred with you right or they will say you know i still have to use their way but in a much more cordial way”, with P being agent sometimes and at other times, his Scandinavian colleagues have agency in the material processes.

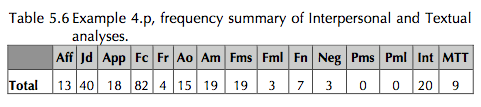

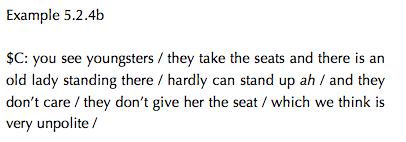

P talks around the concept of assimilation in terms of how he gets along in the office with his Swedish colleagues and how they work things out when a conflict or disagreement occurs. He begins by speaking about his experiences in the office in times of conflict:

Clauses 1i to 11iii contain mostly judgements by P on his Swedish colleagues when working with them in times of conflict, beginning with a strong affective declarative that is indicative of certainty and conviction on P’s part, i can tell you ah in clause 1i. This is followed by the word stubborn in clause 1ii, where stubborn is force amplified with very to render very stubborn in describing his Swedish colleagues’ behaviour. The word very is then repeated twice in clause 2α in a statement that appreciates the situation, that it is a difficult situation to be in and one that is very hard to fight…very hard. For P, the situation is such during times of disagreement that his manner of handling disagreements, the better way to deal with things, is to simply walk away to calm down, the word better being a comparative focus word that is repeated in clauses 3 and 4i.

What seems to go on during a conflict or disagreement is a tug of war of sorts where both parties need to decide which way to go, as indicated from clauses 8i to 11ii. The use of finite modals and focus words such as certain (in 8ii) and still (11ii) show a form of high probability and obligation of sorts in a specific direction of either ‘your’ way or ‘mine’. In clause 8ii, okay okay we will do certain way, the interpersonal theme okay okay indicates a certain backing away from a standoff or a concession of sorts. The use of a finite modal will, together with a focus word certain in certain way (in 8ii) refers to a specific manner of doing things, meaning that one party will need to concede and it is not exactly an assimilation nor integration of working methods that takes place. This underlying tension can be seen in we will do certain way (in 8ii), they will do your way (9β) and i still have to use their way (11ii), the words still have to in clause 11i indicates a high obligation on P’s part to concede. The stubbornness of the Swede is reflected again in clauses 9α through 11iii, even after P describes them in positive judgements as reasonable (in 5β and 6) and cordial (in 11iii), since the other judgements are that they will not apologize to you (in 9α) and that you will ultimately still have to use their way (in 11ii).

In clauses 13i to 18i, P explains his reasons to concede:

P uses a military analogy in clauses 14ii and 14iii to explain hierarchy, rank and titles within the organization. And the only reason for concession in times of conflict, is that the Other is higher up in rank in the vertical hierarchy of the organization, who has more stars on the shoulder, with the focus words more stars repeated in clause 15i. The relational processes is in 16α and 17, describes how P views situations as ‘given’ when one is in corporate life (also a marked theme in clause 17). The mood adjuncts lor (in 13ii), lah (in 15ii) and the tag lah (in 16α) are all Singapore colloquial tags that serve to emphasize the speaker’s point and in this case, they serve to emphasize P’s attitude towards the situation. In clauses 13 ii and 13iii, okay lor you want your way then we do your way the lor serves as an amplification of the word concessive okay, to show that P is indeed giving up his position and giving into the Other. The lah in both 15ii and 16β carry with them a hint of ‘what is obvious’ and also acceptance of what is ‘given’ or taken for granted as everyday knowledge and not something that is questioned. And in clause 18i, P reconfirms this unquestioning attitude, with the use of high obligation words have to in so you have to follow.

A possible hint at an effort towards integration at work can be found specifically in clauses 13ii and 13iii with P’s use of the collective we in you want your way then we do your way. The we indicates that while not all things are smooth sailing within the organization, P still considers the organization as a single unit that needs to move forward together, one way or another. The ultimate effort in moving forward is a singular one.

P gives his ideas and reasons why he sees the two groups of persons, the Asians and the Scandinavians need each other, in clauses 28i to 36ii:

The mental process need in you need the swede (in 28i), you need to do business (in 33β) and you need a Singaporean (in 34iii) indicate that the two groups of persons have little choice but to work together in achieving what they want. As with B in Example 4.n, P is also of the opinion that locals would be best when working in the Singapore business scene. P’s reason is that while knowledge transfer and knowledge sharing is initially needed from foreign talent (in 30i) and the swede (in 28i), where the material process gain indicates that knowledge and technology can be transferred and learned by the local employees, the local still knows best in terms of the local market (in 36ii). The focus words a local is also repeated in clauses 31, 34α and 35i. In clause 31, the marked theme, management wise, coupled with the emphasis tag ah, launches P’s appreciation of the situation, where he advises in a tentative tone as indicated by the comment and mood adjuncts, i think, i…think, i guess so, to use a local. But P goes on in clauses 32 to 35i, arguing his case on why he believes locals are better at doing business on the local scene, concluding with 36ii, the local knows best in terms of the local market. The focus word local and the mental process knows, has as its sensor, the local, with the phenomenon, the local market, indicating that there is some form of tacit knowledge involved when it comes to navigating the local scene, an advantage which foreigners may not acquire as easily.

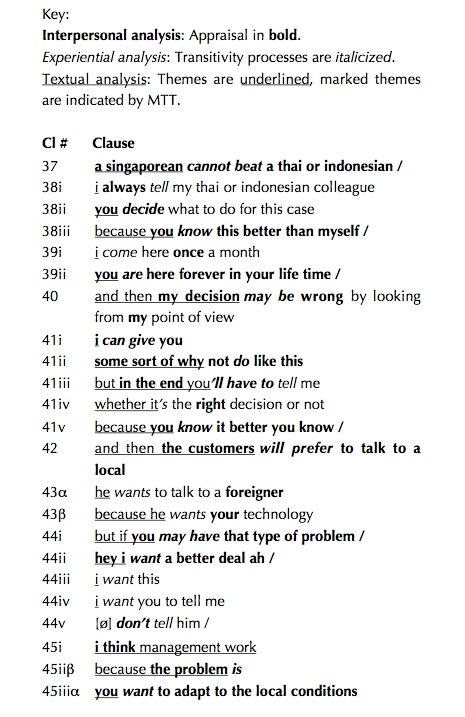

The topic of knowledge of the local market is expanded and addressed by P in clauses 37 to 45iiiα:

The exchange of knowledge and a knowledge of the local market is key for Swedish organizations to be successful in Singapore. This is indicated in clauses 37 to 45iiiα by the number of mental processes dominant in these clauses with a general you as senser, such as you decide (in 38ii), you know this better (38iii), my decision (in 40), you know it better (in 41v) and customers will prefer (in 42). In most mental processes, the sensers are often either a general you or the Other, referring to the local in that respective country, who is more knowledgeable of the local field and can do the job better (a comparative focus word in clauses 38iii and 41v) than P in that situation. In clause 42, the senser is customers, who prefer to talk to the local (the phenomenon of the mental process). This local networking advantage that locals have within their own country is similarly by B in Example 4.n in clauses 31i to 31iii, people speak to them more, tell them more about their future projects they have and so on.

This preference for talking to a local is then followed by the focal words foreigner and your technology in clauses 43α and 43β respectively, indicating that perhaps the only reason for a local to speak with a foreigner is still due to obtaining expert knowledge or specialized knowledge. But when it comes to local conditions (focus words in clause 45iiiα), P also suggests (from clauses 44i to 44v) that locals drive hard bargains, a point which is a similar to a point brought up previously by G in Example 4.m, about local Singaporeans when negotiating, which is that they haggle and bicker (in clauses 6 and 16i respectively, in Example 4.m). In 44i, the negative appreciative words that type of problem describes what P thinks, that the situation is problematic, when locals make unrealistic demands on the deal, i want this, i want you to tell me, don’t tell him (in 44iii to 44v).

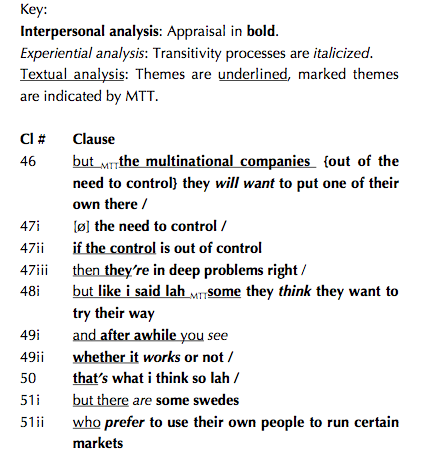

Clauses 46 to 51ii conclude the lines in which P discusses his thoughts on working with Swedes and whether it is the better solution to have locals run the office in a foreign country setup:

The marked themes in clauses 46 and 48i, the multinational companies and some [Swedes] lend focus to the specific entities that P talks about, which are foreigners (specifically Swedes, in clauses 51i and 51ii) and the large foreign owned organizations in Singapore. The clauses are characterized by mostly relational processes which serve to describe the situation in P’s point of view, with the use of is and are in clauses 47i (ellipsed relational process) to 47ii, 50 and 51i, where the situation as P sees it, is problematic if the organizations insist on having foreigners run the local market. The situation as ‘problematic’ is first marked by P’s use of high obligation words such as out of the need to control, repeated in both clauses 46 and 47i, to indicate that the decision to use one of their own there (in 46), is perhaps not negotiable. This non-negotiable need to control becomes problematic if the control is out of control (in 47ii), is said by P perhaps in reference to the view that the foreigner may not necessarily have a ‘local advantage’ or access to a local network that they can access i.e. control or manage.

Still in clauses 48i to 50, P’s attitude is one of concession and allowance, but like i said lah, some they think they want to try their way, and after awhile you see whether it works or not, that’s what i think so lah, the two lah tags emphasising his position of concession, giving his colleagues the freedom and choice to do as they deem fit. P’s attitude is perhaps one that indicates an individual who works towards integration of methods within the organization, as he allows the Other to experiment with their working methods.

To conclude this section, the interpersonal, experiential and textual analyses show that situations of power struggles in the organization between the locals, including P, and their Scandinavian colleagues is not uncommon. Part of working together is to have arguments arise and subsequently solved at the work place. P is not always in a position of power but views that as part of ‘corporate life’, where methods of doing things are constantly negotiated. He feels however that dealing with conflicts with his Scandinavian colleagues is perhaps easier than having to deal with conflicts with fellow Asians since Asians tend to harbour hard feelings. As with G in text example 4.m, P also highlights that Asians tend to drive hard bargains and in that sense, can be difficult to work with.

5.2.3 Words in context analysis

Words in context analysis for the word ‘assimilate’

The word integrate and its variations such as integrated and integration were used a total of 6 times by the respondents in the data. All instances were used by the Scandinavian group of respondents:

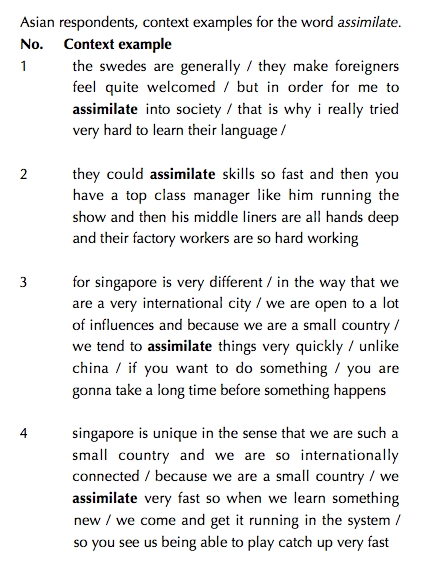

Of the four context uses of the word assimilate, only the first example was used in context to refer to cultural assimilation, where the respondent felt that in order to have greater contact with the Swedish society, that s/he needed to learn the language, perhaps make the language her or his own. In the other three context uses, assimilation is used in reference to skill, dexterity and proficiency of either persons or to a country, in this case, Singapore. The word often co-occurs with the words quickly or fast, in assimilate skills…fast, or assimilate things very quickly and assimilate very fast, with the word assimilate having the meaning of ‘to make one’s own’.

Words in context analysis for the words and ‘integrate’ and its variations

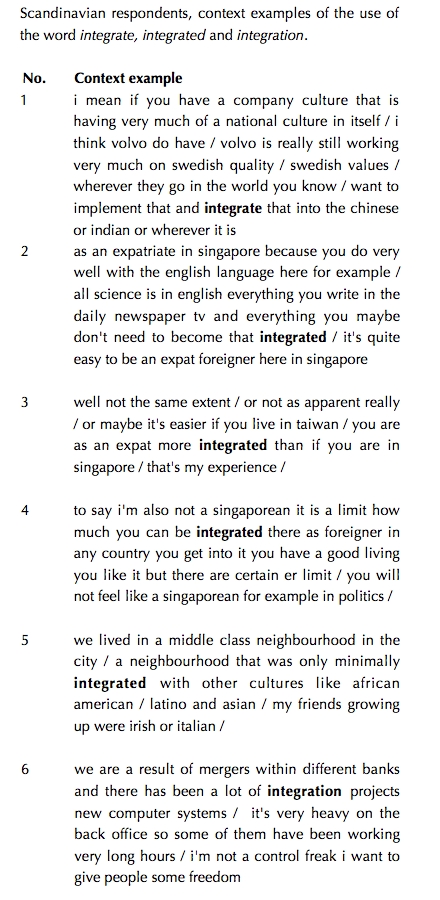

The word integrate and its variations such as integrated and integration were used a total of 6 times by the respondents in the data. All instances were used by the Scandinavian group of respondents:

The word integrate is often used by the Scandinavian respondents in reference to cultural integration and of their life as foreigners or expatriates, explaining the extent of their feeling part of the larger dominant culture, as seen in context examples 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, where the first refers to the integration of corporate cultures. The concept of integration and the process of being integrated into the dominant culture for example, is also seen by the respondents as scalable, meaning that one could be or feel more or less integrated in the foreign society and one the integration process could be one that scales from easy to difficult, i.e. integrated…quite easy, more integrated, how much…integrated and minimally integrated. The word integration is used in the last example to refer to projects and computer systems within the organization.

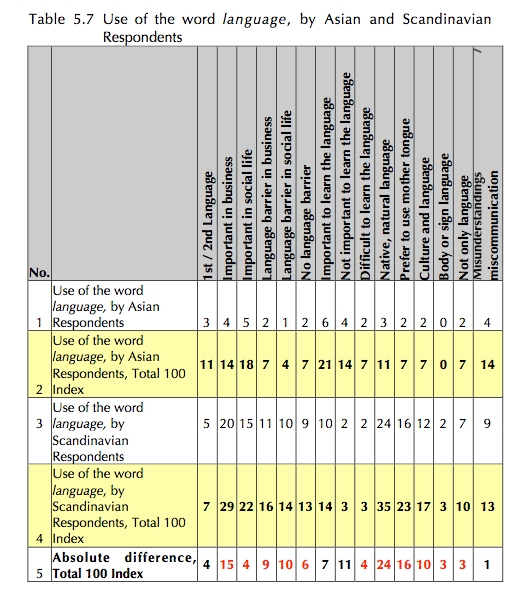

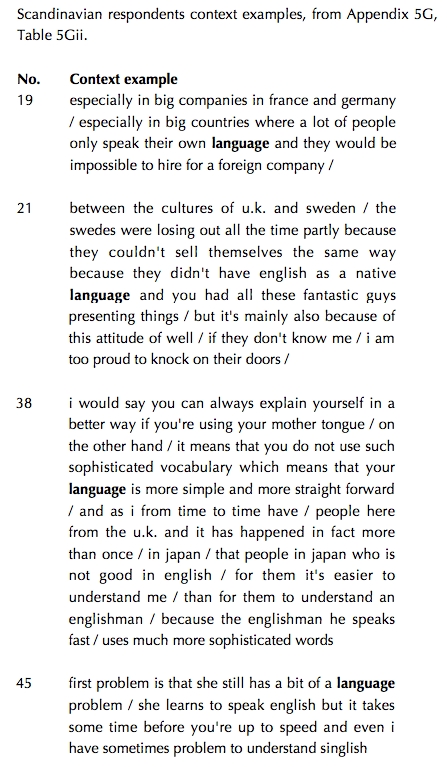

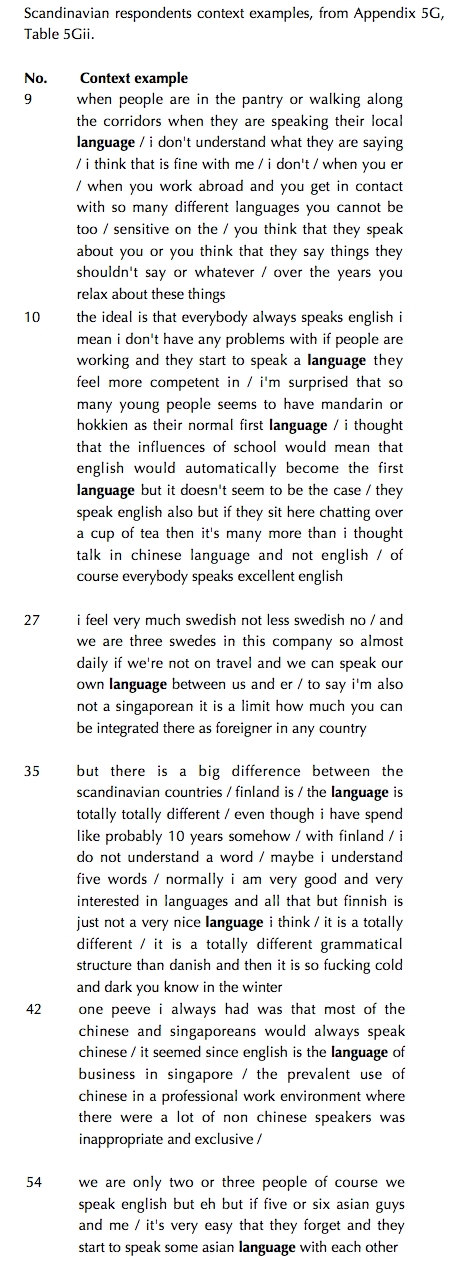

Words in context analysis for the word ‘language’

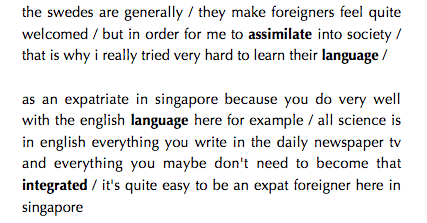

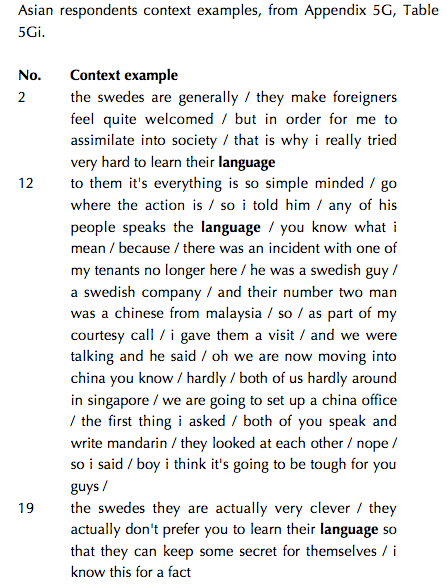

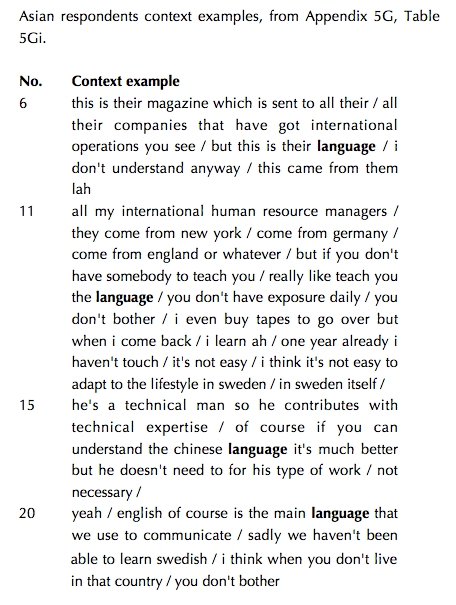

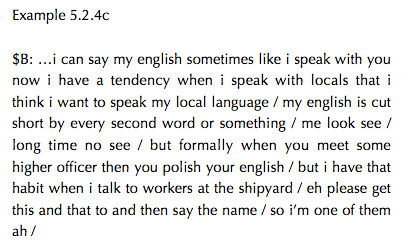

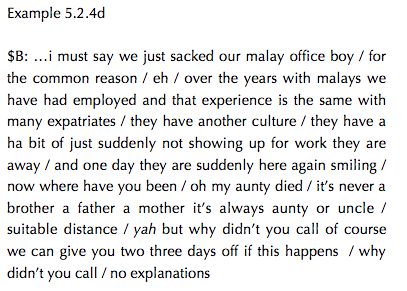

While the words assimilate and integrate had limited contextual uses by both groups of respondents, the idea of speaking the local language of sharing a common language as a factor that helps one feel part of a group was brought up by two respondents, one example from each group of respondents: