This chapter provides an overview of the method of investigation in this study, beginning with the profile of the respondents from Scandinavia and Asia. The data in this study consists of transcribed interviews. The interviews are then managed via a coding process adapted from grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin, 1998) before discourse analysis is carried out. A brief explanation of grounded theory and how its coding procedure is applied to the interview data as a data management tool prior to discourse analysis is presented. The chapter also outlines the systemic tools and framework of discourse analysis that will be applied to selected interview texts in Chapter 5.

3.1 Respondents

As the goal was to investigate the Swedish management style in Singapore, the search for respondents to this study began with a search for Swedish owned and managed organizations in Singapore. The targeted organisations were Swedish owned or Swedish managed organizations based in Singapore as listed by the Swedish Trade Council (Svenska Exportrådet) in 2003/4. Contact information for the top level managers of these organizations in Singapore were also retrieved via a search at the Swedish Business Association of Singapore (SBAS) in 2003/4A synopsis of the study was emailed to a total of about 147 respondents from Swedish owned organizations, both Scandinavian and Chinese top-level managers, together with an enquiry of whether they were interested in participating in the study and if they had time to spare for an interview. As the organizations were Swedish owned or Swedish related, the email was sent to slightly more Swedish or Scandinavian respondents (94 contact emails) than Singaporean or Asian respondents (53 contact emails), since it is usually a Scandinavian name which was listed as the ‘contact point’ for the organization. The response rate with a successful interview was about 25% for the Scandinavian or Swedish respondents, with 23 respondents agreeing for an interview and 18% for the Asian or Singaporean respondents, with 10 respondents agreeing for an interview. Those who declined to be interviewed cited a busy work schedule or that they were travelling and out of the country during the time the interviews were to be conducted.

For those who agreed to be interviewed, interview times were scheduled at their convenience in their offices. 33 long interviews with leaders (both Scandinavian and Asian) of Swedish owned or Swedish managed organizations were conducted in the months of February and December 2004 in Singapore. The interviews were of an average time of 1 hour 39 minutes per interview and rendered a total of 540 A4 pages of transcribed data including 260,178 words.

Of the 33 respondents, 23 were Scandinavian (21 of 23 were Swedes) and 10 were Asians (7 of 10 were Singaporean Chinese). The targeted group of respondents for the interviews were persons predominantly in leading or managerial positions in these organisations, holding such titles as Managing Director, Chief Executive Officer and Regional Director etc. The respondents were randomly selected in the sense that no headhunting was conducted for any particular respondent; no one type of organization was targeted and no one particular industry was targeted. As such, this study prioritised the selection of participants based on the fact that they were leaders in Swedish managed organizations working in a cross-cultural environment regardless of their age, sex, socio-cultural background and the industry field in which they worked. They were selected with the assumption that it was the organizational decisions made and actions that they carried out that influenced and determined the future of the organizations for which they worked. The result was that the respondents came from a wide variety of industrial backgrounds including shipping, finance, food and information technology. And that it was their qualities, personalities and points of view that would be interesting to explore in a language analysis.

3.1.1 Scandinavian Respondents

The Scandinavian respondents seemed in general, more open in their email communication than the Asian respondents. The Scandinavian respondents had more than a 55% response rate (out of the 94 individuals contacted) via email. There were initially more than 23 who were interested in participating in this study but practical reasons such as tight time schedules, frequent travels on their part and the fact that I was in Singapore for a limited length of time, prevented the possibility of more interviews. The success interview rate for the Scandinavian respondents was thus about 25%, from the initial 94 contact emails sent out.

The group of Scandinavians were mostly Swedes with one participant from Norway and one participant from Denmark. They all had expatriate status in Singapore and worked in Singapore on an average of a 3 – 5 year contracts with their companies. There were some exceptions to this, two Swedes for example had worked in Singapore for more than 10 years and the respondent from Denmark had worked in the Southeast-Asian region for more than 13 years and had been living in Singapore for about 9 years at the time of the interview. Otherwise, the Scandinavians as a group were rather homogeneous in working background, where they all worked in top-level management positions such as directors, managers and chief executive officers (CEOs). Many of them travel the Asia-Pacific region on business trips and all had their company headquarters in Singapore.

With regards to topics that relate to the organization, the Scandinavians are more spontaneous in their responses to the interviews as a group. Their spontaneity is reflected in the Organization category of the Main Table, with the Scandinavians having an Index of 1830 for “spontaneous topics”, as compared to the Asian respondents, who had an Index of 1640 for “spontaneous topics”. This is in contrast to the Asian respondents, who spoke more with “prompted topics”, their Index being 1800 compared to the Scandinavians’ 1613 Index. This difference in Index in the Organization category indicates that Asian respondents tended to talk within the given topic whereas the Scandinavian respondents tended to move on to other (related) topics, unprompted by myself as the interviewer. Appendix 3A illustrates the questions that guided the open interview for Scandinavian / Swedish respondents and the indexes is explained in greater detail in the following chapter.

3.1.2 Asian Respondents

The general response rate of the Asians was less than 20% since most did not respond to the contact emails if they were to decline to be interviewed. Perhaps this reflects a certain cultural concept of ‘politeness’ with the Asians, with the avoidance of saying an outright ‘no’ to others. The success rate of interview of the 54 contacted was 18% with 10 Asian respondents agreeing to an interview.

Of the 10 Asian respondents that agreed to be interviewed, 7 were Singapore Chinese, the other three respondents included a Canadian Chinese who had lived in Singapore and Hong Kong for more than 20 years, a Singapore Indian and a Malaysian Chinese who had become a Singapore citizen and who basically considered himself to be Singapore Chinese.

The resulting number of Asian respondents who took part in this study were significantly lower than Scandinavian respondents, not for a lack of approaching them but rather that many Asians who were approached declined, for various reasons, to be interviewed. Luke’s (1998) study reflects to a certain extent, similar encounters when trying to recruit Asian participants in her study. If the persons approached agreed to an interview, they wished to remain anonymous as respondents. The Asian respondents who did agree to an interview were generally friendly, since I too was a fellow Singaporean. There was a camaraderie between myself and the Asian respondents illustrated with most of them using a colloquial version of Singapore English (SCE) when speaking with me during the interview. SCE is a more relaxed form of Standard Singapore English (SSE), used most often to show a sense of belonging to an in-group. Gupta (1998, 1994, 1992) gives more information on Singapore English, their contact features and uses. Appendix 3B illustrates the questions that guided the open interview for Asian respondents.

3.2 The interview process

The research interest with the group of respondents was to study their point of view as reflected in their language use, about working in a cross-cultural environment. Informal conversations with some Scandinavians in Singapore had taken place prior to the interviews proper, where during these casual and impromptu social interaction sessions mostly at cafés in Singapore, it appeared that some expatriate individuals were highly successful in adapting to their new surroundings. They were able to gain the trust of their local colleagues and mentioned few problems in building a network of their own. These conversations left an impression that some have learnt to trust others of a different cultural background, when working in a foreign environment. Some other individuals on the other hand, were quite unhappy, apparently being unable to work efficiently in the new environment; they found it hard to trust the local network and have found difficulties understanding the working culture and felt generally unsuccessful. The concept of success is defined here in the broadest sense, mostly as the expression of a general feeling of well being and ‘feel-good’ on the part of the respondents of working and living in Singapore. Part of this feeling of success is closely tied to one’s ability to adapt and assimilate to the new environment (Shay and Baack, 2004; Leiba-O’Sullivan, 1999; Harris and Moran, 1994;). In adapting and assimilating to a foreign culture, the assumption is that one needs to trust how the Other does things. In most cases, two different cultures may have very different ways of reaching the same goal. In order to reach goal x, the Swedes may choose method a, believing wholeheartedly that method a is the only right / appropriate way to get to goal x; while the Singaporeans may choose method b, believing wholeheartedly that method b is the only right / appropriate way to get to goal x. For both sides, doing things the Other’s way may amount to rocking the very foundation of values and beliefs that one has in order to take on the values and beliefs of the Other, in other cases it may simply be a matter of different habits, for example, which ‘end’ of the egg you open.

It is undoubtedly, not easy to measure success or trust in a numerical fashion, against a backdrop of some perhaps vague standard of measurement, and it is not the intention of this study to come up with such a numerical measurement of how successful the respondents are or how much trust is achieved between the Scandinavians and Asians when working together. It is rather to explore, the respondents’ general sense of cooperation in working together in a cross-cultural environment, as expressed through their use of language when talking about organization activities.

With that in mind, the interviews for both the Scandinavian and Asian groups were designed as qualitative interviews (Kvale, 1996; Warren, 2002) based on a relaxed conversational style. Appendix 3A and 3B give an idea of the questions that guided the conversational interviews for the Asian and Scandinavian participants respectively. What is of interest is each respondent’s point of view, their perspective on reality and how they put their experiences, thoughts and feelings into words when speaking about their working experiences. The ideal atmosphere of the interview would be for the respondents to interact and converse as if we had known each other for a long time, on a casual, ‘good friends’ basis, so to speak. But of course, it was in reality a conversation between people who had not met before.

The interviews were also structured taking into consideration the respondents as individuals, who realized several social roles in society: from father / mother, husband / wife, friend, colleague to manager / employer. The social roles realized by each respondent can be seen as roles fulfilled in broadly two domains; a private domain of home, family and close friends and a public domain of being an employer or an ambassador for the organization and for Scandinavia.

The ten categories of questions that appear in appendixes 3A and 3B were thus deliberately broad and “all encompassing”. The questions for both groups of respondents were overlapping in nature, but not strictly similar since they needed to take into account the respondents’ socio-cultural backgrounds. Appendix 3A shows the questions to the Scandinavian respondents and Appendix 3B shows the questions to the Asian respondents. The respondents were given ample time to ponder the question and reply in their own time and they were allowed to speak as freely and as spontaneously as they wished or could on the topics. The respondents could also choose not to answer questions, according to their discretion. Some follow-up questions also encouraged answers on related topics, so that the respondents might venture into what they thought were related topics. Below are the ten general questions that guided the interviews:

Overview of Interview Questions

1. Candidate’s background information, e.g. how long have you been worked in the company? In travelling for work, where do you most often travel? etc.

2. Culture and organizational culture, e.g. do you see yourself as having a different culture from your Scandinavian / Asian counterparts? Do you perceive a difference in language, values, beliefs, work ethics? etc.

3. Gender / social hierarchy, e.g. how do people address you at the office? What are your thoughts on hierarchy within the organization? etc.

4. Information sharing, e.g. what do you think about information sharing? Are you willing to share information with your colleagues? etc.

5. Preferred method of doing business in Asia, e.g. what is the best way to run a foreign subsidiary? etc.

6. Language barriers and cultural barriers, e.g. what is the official working language at your organization? Do you find people speaking another language, primarily Chinese or Malay at work? etc.

7. Strategies in overcoming language and cultural barriers, e.g. what do you think is the best way to communicate with your workers / co-workers? Do you find that they respond to orders better than group discussions for example? etc.

8. Environment, e.g. have you been to other parts of Asia / Scandinavia? What do you think of the environment there? What are your thoughts on the architecture, the landscape? etc.

9. Food, e.g. how much Scandinavian / Asian food are you familiar with? Do you have any favourites? etc.

10. Protocols, e.g. what are some Asian / Scandinavian protocols you’re aware of when doing business? Are there any taboos? etc.

The aim during the interviews was to listen very carefully to what the respondents were saying and follow-up on subsequent topics of interest that arose in the course of the interview. The questions provided a rough guideline to steer the conversation during the interviews with the respondents interrupted as little as possible. In this way, they were freer to reveal their personal opinions, revealing their point of view (Holstein and Gubrium, 2002).

3.2.1 Recording technicalities

All interviews were recorded with a Sony ICD-ST20 digital audio recorder. Some interviews were recorded on stereo function that facilitates the capturing of better sound quality. The interviews were then downloaded into Mackintosh’s Sound Studio program on a Mac iBook. Mac’s Sound Studio is primarily an audio editing software that allows for mixes and edits of sound. The digital rewind feature enabled a more efficient manner of transcription as it made easy access to specific segments of interview and allowed for repeating the specific time segments as many times as needed in order to obtain an accurate transcription. The average length of time for each interview was 1 hour 39 minutes, which rendered about 2970 minutes or slightly more than 49 hours of interview time in total, all of which were transcribed.

A small number of respondents (3 of 33 respondents or 9% of the respondents) corresponded via email. In these cases, the material will be treated as a written resource.

3.3 Transcription standard

All interviews, except emailed correspondences, were transcribed according to the Göteborg Transcription Standard (GTS) version 6.4 (Nivre et al, 2004). The level of detail in the transcriptions featuring spoken language can vary according to the needs of the study. According to Nivre et al (2004), there are four different transcription standards including:

i. Standard Orthography (SO) – This is used for all words with no special features of spoken language rendered in the transcription. The GTS departs from standard orthography in not using capitalized letters for proper names. No acronyms or abbreviations are used and no punctuation is used. Pauses are indicated by a backslash feature “/”.

ii. Modified Standard Orthography (MSO) – This is used to make clear the conventional pronunciations of spoken language that are not recognized in standard orthography. For example, the /d/ sound in the word and in Singapore Colloquial English, is dropped to render the pronunciation /an/, which may be mistaken for the word an; MSO serves to disambiguate /an/ and /and/ by enclosing the missing letters in curly brackets an{d}.

iii. Phonematic Transcription (PM) – One symbol for each phoneme is used but allophones are not distinguished. This transcription detail level is useful for phonological analyses. This level of analysis also uses a machine- readable phonetic symbol system

iv. Phonetic Transcription (PT) – This level of transcription is most detailed and takes into account features that are below the phonological level such as allophones and co- articulations.

Standard Orthography was the transcription level used for data for the purpose of facilitating discourse analysis, so that the fine details of intonation, hesitation, pronunciation of certain words etc. will not interfere with the readability of the transcript (Potter and Wetherall, 1987). The transcripts are not necessarily machine- readable with such a basic level of transcription. The transcriptions run without the use of punctuation, with no capitalization for proper names.

The interviewer is always labelled “$S” in this study, while the respondent is given the label “$x”, x being any letter of the alphabet from A-Z except letters O and I which may resemble the numbers 0 and 1 in certain instances. The use of a backslash “/” indicates a pause and the number of backlashes used together show the length of the pause; thus “///” would indicate a longer pause than “/”. All text examples used from the interviews in this study will appear as they have been transcribed.

3.4 Grounded Theory as Data Management

3.4.1 Grounded theory

Grounded theory is a qualitative methodology that is so named because it practices the generating of theory from data, encouraging studies to be corpus driven rather than hypothesis testing in nature. As mentioned in Chapter One, ‘theory’ for Strauss and Corbin (1998:15) refers to “a set of well-developed concepts related through statements of relationship, which together constitute an integrated framework that can be used to explain or predict phenomena.” It is not “theory testing, content analysis or word counts” (Suddaby, 2006:636).

Grounded theory’s interpretivist ontology rests on the assumption that human beings do not passively react to an external reality but rather impose their internal perceptions and ideals on the external world and in so doing, actively create their realities (Morgan and Smircich, 1980). This stands in contrast to realist ontology that assumes that the variables of interest exist outside individuals and are therefore concrete, objective and measureable (Burrell and Morgan, 1979). As such, the purpose of grounded theory is not to make truth statements about reality, but rather discover new understandings about patterned relationships and interactions between persons and how these relationships and interactions actively construct reality (Glaser and Strauss, 1967).

Essential to grounded theory is its constant comparative method, the researcher must thoroughly work between data and existing knowledge in an effort to find the best fit or the most plausible explanation for the relationships being studied (Locke, 2001). It is this constant comparative method between data collection, ordering of data and data analysis that makes grounded theory as a qualitative research method, anything but linear in nature and far from an orderly process (Suddaby, 2006).

Grounded theory’s constant and simultaneous comparison between data collection and analysis, and its theoretical sampling in which decisions about which data should be collected next, are determined by the theory that is being constructed (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This means that it is a method that is more appropriate for some types of research questions than others. It is more suited for example, to efforts to understand the process by which actors construct meaning out of intersubjective experience and less appropriate for when seeking to make knowledge claims about an objective reality but more appropriate when making knowledge claims about how individuals interpret reality. Grounded theory should also be used in a manner that is logically consistent with key assumptions about social reality and how that reality is known (Suddany, 2006).

Grounded theory has been applied to various fields including that of sociology, education and learning, management science, organizational research and many more. And in this study, grounded theory is not employed to its full extent, since this study combines both qualitative and quantitative analysis and uses a critical discourse analysis framework as part of the content analysis of textual data. Only the coding procedures of grounded theory are applied to the data as a form of data management.

3.4.2 Concepts, categories and propositions

According to Pandit (1995, 1996), whose work involved the application of grounded theory in a study aimed at generating a theoretical framework on corporate turnaround, the three basic elements of grounded theory are concepts, categories and propositions. Concepts are the basic units of analysis, derived from the conceptualization of data and not data per se. Categories are higher in level and more abstract than the concepts they represent and are generated through the same analytic process of making comparisons to highlight similarities and differences that is used to produce lower level concepts. Categories provide the means by which theory can be integrated. The third element of grounded theory is propositions, which involve conceptual relationships (Whetten, 1989:492) indicating the relationships between categories and concepts. The process of grounded theory is inductive, where phenomena are discovered, developed and provisionally verified through systematic data collection and analysis of data pertaining to that phenomenon. Data collection, analysis and theory should have reciprocal relationships with each other and not be isolated processes to each other (Strauss and Corbin, 1990, 1998).

The version of grounded theory coding procedures used for this study is derived from Strauss and Corbin (1990, 1998), whose work, gives specific and systematic guidelines on how such qualitative research be accomplished, emphasising at the same time, a great amount of flexibility and creativity on the part of the researcher when applying the procedures. Researchers should be “unafraid to draw on their own experience when analyzing materials” because such a process would form the foundations for making comparisons and discovering properties and dimensions (Strauss & Corbin, 1998:5).

It is the coding procedures and the resulting topics and concepts that have mostly been applied in this study as a form of data management and organization. During the coding process applied in this study (explained further in section 3.5.1), the word topic is defined in this study as any idea, thought, event or subject that the participants raise during the interview. Concepts in this study refer to a network of topics that can relate with each other to create a general theme. Categories in this study (there are 6 main categories in this study presented more fully in the next chapter of the thesis) hold all topics raised by the respondents.

3.4.3 Coding Procedures: how to derive concepts and categories

According to Strauss and Corbin (1998:101), open coding is the “analytic process through which concepts are identified and their properties and dimensions are discovered in data”. The purpose of open coding is to uncover ideas, thoughts and meanings contained in texts so as to name and develop concepts. Naming phenomena enables the researcher to group similar events, happenings, objects and actions into a common heading or classification. Once classified or conceptualized, the researcher can more easily identify characteristic traits or properties of that phenomenon by doing cross-comparisons between concepts. During the process of open coding, data are broken down into discrete parts, closely examined and compared for similarities / differences. Events, happenings, objects and actions / interactions found to be conceptually similar in nature or related in meaning are grouped under more abstract concepts to form categories. The categories are further differentiated according to their similarities / differences in properties.

There are several ways a researcher can conceptualize phenomena and carry out the open coding process. The researcher can carry out a line-by-line analysis, which involves close examination of data, phrase by phrase and sometimes word by word. The word by word microanalysis, which often begins with the very first word of the respondent’s quotation is the most time consuming process, for example the researcher might ask what is the meaning of the word “red” as used by the respondent and what other wider possible meanings can “red” refer to? An example of microanalysis can be found in Strauss and Corbin (1998:59-71). A second manner of coding is capturing ideas by sentences or paragraphs, for example while coding, a researcher might ask, “What is the major idea brought out in this sentence or paragraph?” After naming or labelling the idea, the researcher can then go back to do a more detailed analysis of the concept. The third manner of coding is to peruse the entire document and ask, “What is going on here?” and “What makes this document the same or different from, the previous ones that I coded?”

A researcher can also label incidents, ideas, events, acts and phenomena, by using in-vivo codes (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) and non in-vivo codes, wherein the former refers to the name of the concept as taken from the words of respondents themselves and the latter refers to the name given by the researcher due to the imagery or meaning the concept invokes in context during the comparative process. Strauss and Corbin (1998) highlight that the context within which the research and the data is collected plays an important role in non in-vivo codes. By “context”, they mean “the conditional background or situation in which the event is embedded” (Straus and Corbin, 1998:106). A brief coding procedure example, with the coding in square brackets and in bold font from Strauss and Corbin can be found below. The context is teen drug use, which is different from adult drug use in the sense that part of being a teen is often having an exploratory nature, a need or desire to challenge adult values and sometimes rebel against them. A different situation will arise if the context were adult drug use.

Coding example from Strauss and Corbin (1998:106-107):

Interviewer (I): Tell me about teens and drug use.

Respondent (R): I think teens use drugs as a release from their parents [“rebellious act”]. Well, I don’t know. I can only talk for myself. For me, it was an experience [“experience”][in vivo code]. You hear a lot about drugs [“drug talk”]. You hear they are bad for you [“negative connotation” to the “drug talk”]. There is a lot of them around [“available supply”]. You just get into them because they’re accessible [“easy access”] and because it’s kind of a new thing [“novel experience”]. It’s cool! You know, it’s something that is bad for you, taboo, a “no” [“negative connotation”]. Everyone is against it [“adult negative stance”]. If you are a teenager, the first thing you are going to do is try them [“challenge the adult negative stance”].

I: Do teens experiment a lot with drugs?

R: Most just try a few [“limited experimenting”]. It depends on where you are [and] how accessible they are [“degree of accessibility”]. Most don’t really get into it hard-core [good in vivo concept] [“hard core” vs. “limited experimenting”]. A lot of teens are into pot, hash, a little organic stuff [“soft core drug types”]. It depends on what phase of life you’re at [“personal developmental stage”]. It’s kind of progressive [“pogressive using”]. You start of fwith the basic drugs like pot [“basic drugs”][in vivo code]. Then you go on to ttry more intense drugs like hallucinogens [“intense drugs”][in vivo code].

I: Are drugs easily accessible?

R: You can get them anywhere [“easy access”]. You just talk to people [“networking”]. You go to parties, and they are passed around. You can get them at school. You ask people, and they direct you as to who might be able to supply you [“obliging supply network”].

I: Is there any stigma attached to using drugs?

R: Not among your peers [“peer acceptance”]. If you’re in a group of teenagers and everyone is doing it, if you don’t use, you are frowned upon [“peer pressure”]. You wan tot be able to say you’ve experienced it like the other people around you [“shared peer experience”]. It’s not a stigma among your own group [“being an insider”]. Obviously, outsiders like older people will look down upon you [“outsider intolerance”]. But within your own group of friends, it definitely is not a stigma [“peer acceptance”].

According to Strauss and Corbin (1998:114), “Categories are concepts, derived from data, that stand for phenomena… Phenomena are important analytic ideas that emerge from out of the data. They answer the question “What is going on here?” They depict the problems, issues, concerns, and matters that are important to those being studied.” In addition, the name chosen for a category is usually one that seems the most logical descriptor for what is going on and should be a vivid referent for the researcher. The perspective of the analyst, the focus of the research and the research context also determine how categories derive their names. As such, different analysts may decide to name similar phenomena under different names, depending on the context of research. Taking an example from Strauss and Corbin (1998:114), one analyst might label birds, planes and kites as “flight” whilst another might name them “instruments of war” because of the context of research, since birds might be used as carrier pigeons delivering messages to troops behind enemy lines, planes as troop and supply carriers and kites could be used as signals of an impending attack.

Categorizing should be done once concepts begin to accumulate, so that the analyst can then begin to group these concepts into categories under more abstract explanatory terms. Once categories are identified, they can be developed in terms of properties and dimensions. Subcategories can also result from categories.

3.5 Coding procedures in this study: deriving concepts and categories

The tradition of writing and presentation of a study calls for a somewhat linear arrangement of information, a typical presentation of an academic study for example would have the following sections more or less in sequence, identifying area of research, collecting data, sorting data, analyzing data, presenting findings and conclusions. The manner of presentation of a piece of academic research work means that it limits the way in which the dialogic process that goes on between researcher and data can be conveyed in writing. As such, the interpretive dialogic style of the coding procedures that occurred during the data management and sorting phase of this study is difficult to convey in a linear manner.

As such, the non-linear nature of grounded theory as a qualitative method and difficulties in expressing this in the linear system of writing, should be taken into account when reading works that apply grounded theory as a method. Grounded theory allows for the study to be corpus driven and offers a fairly systematic, interpretive and dialogic manner in which to categorize or code concepts through in-vivo and non in-vivo means.

To that extent, what has been employed in this study are the theoretical concepts and categories that actually emerged from the data of this study, so that this study is corpus driven and its resulting categories, containing its respective topics, are presented in the Main Table in Appendix 3C. A summary of the results of the coding procedures will be presented in Chapter 4 with a complete list of categories and topics found in the Main Table in Appendix 3C.

3.5.1 Open coded topics

Strauss and Corbin’s (1998) method for the coding of interviews was used for the data consisting of 33 interviews. The topics from the data are either prompted or spontaneous; the former referring to topics brought up by myself as the interviewer or a word that has been used by the respondents in their response to a question. If the respondent uses the same word as used in the question, then s/he is using the word explicitly and the topic is coded as one that is occurring in-vivo (corresponding to Strauss and Corbin’s in-vivo concepts). If the respondent speaks about the prompted topic but does not use the same word as that suggested by the interviewer, then the respondent is speaking implicitly about the topic and it is coded as non in-vivo. The latter spontaneous topics refer to topics brought up of the respondents’ own accord. Spontaneous topics can also be in-vivo or non in- vivo. Each interview was meticulously coded for both in-vivo and non in-vivo concepts, line by line. For the purposes of this study however, what is reflected in the Main Table in the appendix are prompted and spontaneous topics and whether these were in- vivo (labelled explicit in the Main Table in Appendix 3C) or non in-vivo (labelled implicit in the Main Table in Appendix 3C), so as to gain an understanding of the natural interests of the respondents when speaking of certain topics. An example of the coding procedure is given below, with the topics in bold.

Coding example from this study:

$S: do you see a singaporean identity in doing business or

$M: perhaps it’s uhm / only because i hear other people have those views / but i were to compare chinese and malays and indians [ethnic groups in Singapore]/ of course i can see a difference / i don’t know if it’s true though / because my experience again is mainly chinese / but seriously i would like to say / no [personality of person] / i don’t see a big difference / i don’t prepare to behave differently because i know it’s an indian or malay / i tend to approach it the same way / [need to be ‘open’ as individuals]

$S: this organization is swedish / the organizational culture here is it more swedish or is it more

$M: more swedish

$S: how so / the values or

$M: the values are swedish / [company culture] that’s one of the most important tasks that we have that when we come to singapore from sweden / is to carry the culture / we are called / we are sometimes called culture carriers [Swedes as ‘culture bearers’]/ and therefore it’s important for us to have swedes or nordic people / you can say it’s finland denmark norway sweden / can all serve as cultural carriers because we have business in all those countries / so in addition to the business tasks or business responsibilities / we also have the responsibility to transfer or carry over the culture [tacit knowledge] / one example maybe um / can describe this / when i took over as general manager in 1998 / so i came over in another position than general manager position / 1998 i was appointed g m for asia [expert knowledge / specialization] / and at that point in time / there were more or less nine hierarchic title levels in the bank / i mean everything from junior clerk / clerk / senior clerk / junior officer / officer / senior officer / so nine sort of title levels and nine [hierarchy] / all levels also had a number of value of annual leave days / as an officer you had one more day than a junior officer / despite the fact that other swedes have / been g ms here / i don’t know why they didn’t find interest to do something about it / but in the bank back home / we have three [flat / lateral hierarchy in organization] / so i changed that to three / which mean i couldn’t take away titles / because that would be very sensitive / but i tacked them in three main levels [flat / lateral hierarchy in organization] and i took away all links to annual leave days / it doesn’t come from your title / it comes from the number of years in the bank / which is the same in sweden / everybody starts from the same level and then you add on due to age and due to position [hierarchy] / meaning the responsibility you have / not your title / if you have a big responsibility / you’re entitled to two more days / so that i changed / i re did the entire employment hand book because it was quite singaporean style / it said more or less in every page that everything was uhm / at the discretion of the general manager [‘the boss is the boss’] / which is not the case in the rest of the bank that staff should / the staff have rights and obligations / and these are explained and informed in the bank’s employment handbook / so i took that away / but what can be applied here / i took it over here / everything cannot be applied because the business here is more limited than back home [integration] / so a lot of those changes on the soft side / and then i also changed the organization so that instead of having one boss here and many people underneath / and he was sort of giving instructions to all of them / i took away the boss and opened up so that the responsibility was on more people and everybody had more to say / more to decide over / more influence / but they also exposed more / so customers if they called in directly you have to be able to answer / you cannot go to the boss because he’s not there anymore [giving responsibility / decentralizing power / delegating work] / so that higher exposure was a bit painful for them / because they were not trained before / so of course that you can only do if you add on education / training [competence training] and you give responsibility without taking it back / that you give a service they can take care and i will still have the responsibility [giving responsibility / decentralizing power / delegating work] if they make a big mistake / it’s still mine [making mistakes] / but i cannot say okay / you take care of this / but i also check what you do / you cannot do that / so you have to decide if you can decentralise responsibility [giving responsibility / decentralizing power / delegating work] and then stay / that took also some time / but now they can / they can [learning]

$S: do you find singaporean workers very straight / very narrow thinking / i would think that in the beginning with this new layout they might’ve been quite scared

$M: absolutely / that is very much the picture everybody sees when you arrive first time [get a broader vision] / and is still very much the case / i think that is still something that will take a longer time to change [integration] / my personal view is that it comes from this / very hierarchic history / and then you have uhm / and since / the chinese society has er / i mean if you look back in history [sense of ‘history’] / if this was sweden and this was the swedish king running the country / he was probably or possibly a very bad king or he was a very good king / but even if he was a bad king / he tried his best to serve his people / uhm and if he failed / they were not happy / and maybe he was replaced by his son earlier than necessary i don’t know / but if this was a chinese tzar / he did not do his best for his people / he did whatever he could for himself first / and when he was sort of removed from power [hierarchy] / everybody that had supported him was also removed from power / i mean / i look very / in very broad lines / far back / i’m not saying that is the case today / but history [sense of ‘history’] always forms a country’s traditions / and of course if / if you were killed or removed or head chopped off because his head was chopped off / then it became quite dangerous to do anything else than you were ordered to do [Chinese don’t wish to ‘stand out’] / don’t show your extraordinary support / don’t liaise with him unless you know exactly what you get back / so basically it was safer to stay within your box / if you go out / somebody can chop off your arm / and power is / power is often knowledge information and if you were afraid to lose your power / then you want to do everything you can to keep it / including knowledge / don’t share knowledge because he could be the one killing you to take over / so keep knowledge here / only give small pieces of information down to everybody else / safer for me [information sharing] / so my view is that / this tradition to only do within your small box comes from / and i don’t think you necessarily are aware of your behaviour everyday / it’s just that it comes from generations of behaviours given to you as your heritage [sense of ‘history’] / and i think this will change but it will take time / that is one of the important things i’ve tried to change here / it’s that i actually take the responsibility even if they make a mistake [making mistakes] / i actually give the responsibility [giving responsibility] / not only responsibility but possibilities for them to grow as they would like to grow / as they would like to expand / so often i’ve used that expression / okay this is your box today / find out what you can see out here [thinking outside the box] / and actually there are at least two maybe three / definitely two people here on a management level that have taken this opportunity / so before i couldn’t see at all that they have this [learning] / er helicopter view / i didn’t realise that they could / they had it / but i’ve told them okay this is your chance / you have to do what you want to do with it / and as i said / two actually definitely grew into the costume [learning] / i enjoy this / and they started to make their own decisions [decision making] / they started to be creative [creativity] / they started to be unafraid [learning] / and they have this helicopter view / and so they see ah / oh why / why are they moving from a to b over that side / why do we do that / what does it mean / instead of before saying / oh they are moving from a to b but er okay / continue / yeah <>/ big difference

@ < laughter >

This coding procedure rendered a total of 252 open coded topics, of which 122 (48%) instances were spontaneous topics, and 130 (52%) instances were prompted topics, as reflected in the Main Table in Appendix 3C. Prompted and spontaneous topics are defined only in relation to whether it was the interviewer who had raised the topic (prompted), and it was subsequently picked up by the respondent or if it was the respondent who raised the topic by themselves (spontaneous). Topics are also recorded as ‘prompted’ or ‘spontaneous’ in the first instance that it occurs in the interview transcripts. The numbered column to the extreme left of the Main Table reflects the order in which the OCC have been coded, as and when the respondents have spoken of the topic. “No. 1” of the OCC for example, reflects it being the first topic to have been coded during the open coding process when going through the transcriptions.

Apart from the prompted and spontaneous differentiation in concepts, the dimensions implicit (non in-vivo) and explicit (in- vivo) topics or concepts in language use were added, which correspond to Strauss and Corbin’s (1998) coding procedures, though labelled differently for the purpose of this study. The addition of the implicit / explicit dimensions is related to the point of view and assumption that there is no thought without language since it is a cognitive resource for categorization and meaning making and a reflection of the subconscious (Allwood, 2006). Sometimes, it is what we do not say that tells more than what we say, thus reflecting our implicit or tacit knowledge. The implicit and explicit categories reflect this point of view on language and the categorization of utterances into these dimensions depended on whether the respondent spoke of the topic by explicitly referring to it or whether it was implied, indirectly referred to or perhaps not commented on. For example, the prompted concept of food is recorded as explicit if the respondent uses the word food in response to my question and it is recorded as implicit if s/he makes reference to being hungry or makes reference to specific dishes like prawn noodle soup.

Each of the 252 OCC in the Main Table had the possibility of being referred to a maximum of 33 times in either the implicit or explicit categories since there were 33 respondents. But the number of times a single participant referred to or spoke about a concept implicitly or explicitly within their interview time frame is not reflected in the Main Table. This means that what was recorded was whether or not a respondent spoke of the topic at all and whether they spoke of it implicitly or explicitly.

Thus for every interview, the prompted and spontaneous occurrences of a topic were registered as a yes=1 (the number 1 could well be signalled by using an x too, symbolically marking a presence of the topic either occurring as prompted or spontaneous). How many times a respondent speaks of the topic using a particular word or how they spoke of it (positively or negatively) is not reflected in the Main Table. How a respondent speaks of a topic will be analyzed linguistically via the linguistic framework outlined in the previous chapter.

As there were 10 Asian respondents to 23 Scandinavian respondents, a 100 index was created with the purpose of being able to compare the two groups on ‘equal footing’. The following formula was used to calculate the 100 Index:

Occurrences / Population x 100

The 100 Index numbers calculated in the Main Table reflect the data as if each group of respondents consisted of 100 individuals. The 100 indexes as reflected in the Main Table, makes comparable the numbers between the two groups, enabling a fair assessment of quantities between the Asian and Scandinavian groups. All indexes were rounded off without the use of decimals. With the open coded topics being delineated accordingly with prompted, spontaneous, implicit and explicit utterances, what results is a four-way delineation of the data as reflected in Diagram 3.1. It should be noted that the prompted and spontaneous instances are absolute numbers with 130 and 122 respectively, while the numbers reflecting the implicit and explicit topics in language use, were taken out of 2 groups of respondents of different sizes, resulting in 2481 instances for a total of 33 respondents. In order to make this information useful, the 100 Index was used to enable a comparison between the 2 groups of respondents.

The total index number for both implicit and explicit occurrences is 2481 = 100% for use in Diagram 3.1. The total instances of explicit occurrences for the 252 open coded topics, for the 33 respondents is 988; the total instances of implicit occurrences of language use is 1493.

Diagram 3.1 Groups of Open Coded topics, showing Implicit and Explicit values (total of 2481) for the Prompted and Spontaneous categories.

|

A. 524 instances or 21% |

B. 969 instances or 39% |

|

C. 529 instances or 21% |

D. 459 or 19% |

Prompted 130 topics

Spontaneous 122 topics

Implicit (Non In-Vivo) 1493 Instances

Explicit (In-Vivo) 988 Instances

- Group A (Prompted, Implicit), 21% of the total data – This group contains subjects / themes that were brought up by the interviewer i.e. prompted, in the form of a question. Respondents did not use the same word as the interviewer when talking about the topic but talk around the subject / theme by referring to related topics brought up by the interviewer.

- Group B (Spontaneous, Implicit), 39% of the total data – This group contains subjects / themes that were not prompted by the interviewer but were spontaneously brought up by the participants. The coding for such topics was ‘implicit’ in manner or non in-vivo. This category mostly reflects subjects / themes that are ‘silent’, implicit or not consciously reflected upon by the respondents; what the respondents are saying when they are not saying it. This category potentially reflects a respondent’s implicit knowledge; what the respondents do not know or are unaware of that they know.

- Group C (Prompted, Explicit), 21% of the total data – This group contains subjects / themes that were brought up by the interviewer in the form of a question and the same words are subsequently picked up by the respondent in response to the question / inquiry. So these topics have been coded as prompted and in vivo.

- Group D (Spontaneous, Explicit), 19% of the total data – This group contains subjects / themes that were not prompted by the interviewer but were spontaneously and explicitly referred to or talked about by the respondents. The same word that the respondents used was also used as coded topic, i.e. in vivo. This category presumably includes subjects / themes that the respondents are most aware of, indicating the most current or pressing issues that are of interest and concern to the respondents at the time of the interview.

The numbers for the above delineation of data can also be retrieved from the Main Table in Appendix 3C, where data is presented for both the Scandinavian and Asian groups.

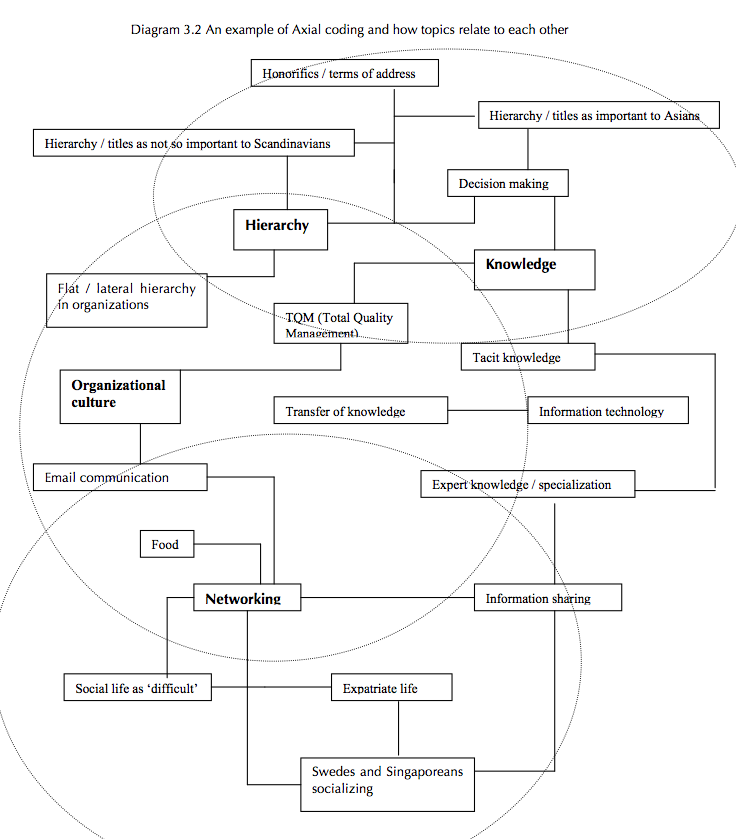

3.5.2 Axial coding and the forming of concept networks

The organizing of the 252 topics into larger concepts and subsequently into more abstract categories was done simultaneously, by axially coding the concepts. The axial coding of concepts meant that the topics / concepts were cross- compared and cross-related to form networks of topics / concepts. The process again was dialogic and interpretive in nature, with numerous cross-comparison of data, this time, for each topic’s properties and dimensions, so that topics that shared similar features could be grouped together under larger concepts and then into categories. Because of the dialogic nature of the coding processes, it would be inaccurate to state that the open coding of topics came first, followed by the process of axial coding in a linear manner. The process of axial coding or creating a network of concepts was rather, an iterative one where topics and subsequently concepts, were dialectically related; each group helping to define and redefine the other as the data management phase in the study progressed (Strauss and Corbin, 1998).

Axial coding was also accomplished and accompanied by the use of memos and hand-drawn diagrams kept as memos. What this meant was that once the open coding process accumulated a certain number of topics, each topic was revisited and studied for its dimensions and properties. Studying the dimensions and properties of a topic helped in identifying which other topics shared similar properties and if so, how they could be related and further studied. This cross-comparison of topics for similar / dissimilar properties and dimensions allowed a mapping of a ‘network’ of related topics that resulted in concepts. The resulting network of concepts could then be re-organized into larger, more abstract categories. An example of the axial coding process with the use of memos in the form of mapping diagrams can be found below in Diagram 3.2. The dotted ovals show the over-lapping areas of topics. The memos are notes of why, how, which and what topics were related to each other. Potential and new concepts that are larger and more encompassing that could be formed were also written in these memos.

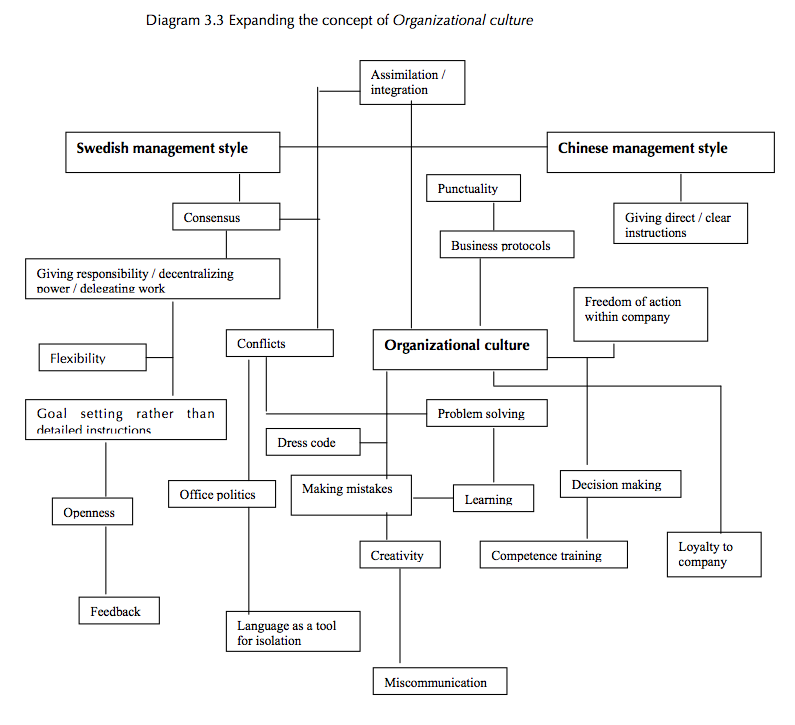

The larger, more general concepts are shown in bold print in Diagrams 3.2 and 3.3. The concept of Knowledge in Diagram 3.2, is an example of a larger concept that did not appear in the 252 open coded topics, but was derived from the other surrounding topics such as information technology, information sharing, tacit knowledge etc that come together under Knowledge. The general concept of knowledge can then be pursued for further research depending on the research questions.

Diagram 3.3 shows the related topics to the larger, more general concept of Organizational Culture, which in turn relates to both the concepts of Swedish Management Style and Chinese Management Style.

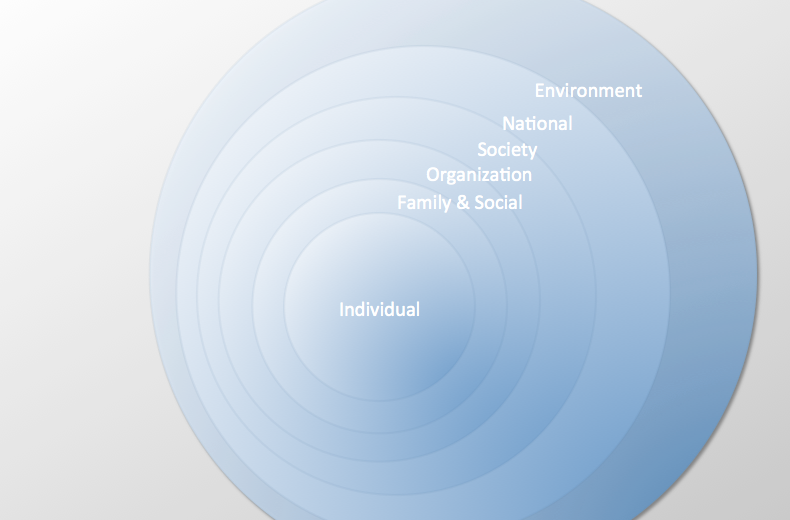

3.5.3 Categorizing concepts

Diagram 3.4 shows how each of the 252 open coded topics were analyzed for their dimensions and properties in relation to the context of the study and then placed into 6 broad categories. The 6 categories relate from a socio-cultural context with the individual as the core of the makings of a society. The categories are shown as radiating outwards from an inner-core, beginning with the most specific entity, in this case, the individual. The context then radiates outwards, moving to encompass larger units of the social fabric, such as the family and social category and then organization, society and national and environment. The result of this categorizing process is that it enables a more organized and consistent manner in which to view and further analyze the data. The categories are as follows:

Diagram 3.4 Axially coded themes, radiating from the Individual at core, to the Environment at outermost radius (Cordeiro-Nilsson 2009: 81)

i. Individual – within this delineation are all topics that reflect upon the respondent as an individual in terms of self-identity, relating to one’s awareness of oneself and of their immediate surrounding.

ii. Family and Social – this delineation that follows immediately after the Individual category, reflects its proximity of concern to the respondent as an individual. Within this are all topics reflecting the respondents’ awareness of their family and immediate social considerations.

iii. Organization – this delineation contains topics relating to the workings in and around the organization in which the respondents are active.

iv. Society – this delineation reflects the respondents’ topics pertaining to the social and the society at large. Society here is seen as a part of the nation where a nation can contain many social groups of people or many societies.

v. National – this delineation reflects topics that pertain to the national identity and the national heritage of the respondent.

vi. Environment – this delineation reflects topics containing references to the larger environmental issues that may have socio-cultural and political consequences. A global perspective is also included in this category with responses relating to climate, conservation of buildings, pollution etc.

The foundation for the concentric circles in Diagram 3.4, is derived from the point of view and the assumption that it is individuals who together, make up a family, a society, are part of an organization, a nation and it is we who collectively also affect the environment by how we create our surroundings and how we use our earthly resources. The Individual at the core also reflects the interview style and process, since a large part of the focus was on the respondents as individuals working in a cross-cultural organization and environment, to uncover the characteristic traits that made them successful as leaders of some very large, multi- national organizations; the success of the organization being evident from their continued presence in Singapore and expansion in Asia.

The categories also reflect better, the structure of the interviews, where topics related to the Individual, Family & Social, Organization etc. categories, can be more easily accessed. While the topics may seem separate in their categories, it would be inaccurate to strictly delineate or designate topics belonging to only one category. Most topics can and do relate in some way to other categories. For example, the topic of learning, which was placed under the Individual category, can also be easily placed under Organization since people tend to learn on the job. In this way, the categories formed can be seen to a large extent as a data management method that helps sort topics in a cohesive manner, facilitating the linguistic analysis in later chapters.

In order to limit the size of the data for a research study that can be carried out by a single individual, the linguistic analysis section to this study will focus on topics from the Organization category. The topics of interest in the Organization category will also need to be used by at least 50% of all respondents.

3.5.4 Departure from grounded theory

It is only the coding procedure style, adapted from Strauss’ and Corbin’s (1998) version of grounded theory that has been applied to the interview transcripts as an information and data management tool. Grounded Theory as a complete qualitative method for research is not applied in this study since the focus of analysis is discourse analysis as a tool to study management styles and language use.

For the purposes of textual analysis, a language analysis framework adapted based on critical discourse analysis (CDA), Halliday’s systemic functional linguistics (SFL) as tools to support the discourse analysis of sections of the interviews, and a ‘words in context’ analysis of specific words as they were used in context by the respondents will be used. The following sections will outline the framework of analysis.

3.6 Textual analysis framework

3.6.1 Systemic functional linguistics

While the previous chapter gave a broad overview of systemics functional linguistics, the following sections will give details on the specific tools that will be used in the text analyses in the following chapter.

The details of the choice of wordings used in the interviews reflect the speakers’ point of view and ideologies. As such, adopting a linguistic framework of analysis based on Halliday’s (1994) systemic functional linguistics (SFL), has the purpose of lending greater consistency to the analysis procedure of texts, allowing for the systematic uncovering / unfolding of the points of views and ideologies of the respondents on various topics. SFL, as with the grounded theory coding process, is also a corpus based and empirical approach to the analysis of the data.

While all three metafunctions are found simultaneously in language, this study is most interested in the respondents’ point of view on working in a cross-cultural environment. Their points of view and ideology (or everyday assumptions, values and beliefs) as reflected in the interpersonal and ideational elements of their speech is what will be explored in this study. The framework for doing so, is based on Halliday and Matthiesson (2004) and Martin and Rose (2003) and it consists of the following elements:

I Interpersonal – appraisal analysis

- Modality – probability, usuality (modalization); obligation, willingness (modulation)

- Adjuncts – Mood adjuncts, comment adjuncts and polarity adjuncts

Linguistically, mood and modality are expressed in the modal verbs and adjuncts. The function of an analysis of mood, comment and polarity adjuncts will aid in uncovering the speaker’s judgements, opinions and feelings, which will be revealed in their choice among different linguistic features. Analysing appraisal features helps uncover the speaker’s adopted stance and attitude towards any given topic or when speaking of events / happenings. It also helps regulate the interpersonal positioning and relationships.

II. Ideational – transitivity analysis of the six processes of material, mental, behavioural, verbal, relational and existential.

Linguistically, this aspect of the analysis will focus on the nominal groups and processes (finite verbs) in the clause structure. It helps identify what the speaker is doing, thinking, saying etc and with whom these events are occurring. The function of a transitivity analysis is to uncover the speaker’s ideas and experiences, how their views of the world are expressed.

III. Textual – theme analysis

Linguistically, an analysis will be made of the theme / rheme development in the discourse. The function of a theme analysis is to uncover the logical development within the clause structure. This can be determined and traced by observing the development of the theme / rheme pattern and what the speaker uses to launch further ideas.

IV. Words in context analysis that allows a cross sectional view of certain words from the entire data

Since the SFL framework will be applied to only selected text examples and not the entire data or corpus, a section analysing ‘words in context’, will help gain access to the entire data of interviews. A concordance software, TextStat (Nieuwland, 2005) will be used to help situate the keywords as they were used in context by all the respondents. This will enable a cross section of the entire corpus of data, all 33 interviews, to be accessed and analysed for patterns and meanings of a specific word use and how the various groups of participants use particular words and what meanings they attribute to that word.

The following sections will present in detail, the linguistic tools to be used in the interpersonal, ideational, textual and words in context analyses.

3.6.1.1 Interpersonal analysis – appraisal

Appraisal refers to the attitudinal colouring of talk along the range of dimensions including: personal conviction, emotional response, social evaluation and intensity, allowing an individual a set of resources to position himself / herself in the discourse interpersonally and is thus an efficient and comprehensive tool in the study of interpersonal relations. Appraisal as a language tool allows for a speaker to engage himself / herself varyingly in the discourse as the text unfolds. Key references in Appraisal include Iedema, Feez and White (1994), Martin (2000, 1997, 1995a, 1995b), Coffin (1997), Eggins and Slade (1997), Martin (2000) and White (2000).

The range of resources available for expressing attitudes, include, Affect which is the resource for expressing emotion, Judgement which is the resource for judging character and Appreciation, which is the resource for valuing the worth of things. Table 3.1, adapted from Martin and Rose (2003:24) shows the basic system / options for appraisal.

Table 3.1 Basic system / options for appraisal (Martin and Rose, 2003:34)

|

1. Attitude |

a. Affect e.g. envied, torn to pieces |

|

b. Judgement e.g. a bubbly vivacious man; wild energy, sharply intelligent |

|

|

c. Appreciation e.g. a top security structure; a beautiful relationship |

|

|

2. Amplification e.g. sharply intelligent, wild energy |

|

|

3. Source e.g. he was popular with all the teachers in the school; all other students envied him.

|

|

Attitudes can also be graded, amplified or downplayed and attitudes can be attributed to sources other than the speaker / writer.

Each system will be described in greater detail in the following sections in the following order of Attitude, Amplification and Source.

Attitude

Affect: expressing feelings and emotions

Affect is concerned with the emotional response and disposition of the speaker in the discourse and it is one of the more obvious ways in which a speaker / writer can adopt a standpoint towards a happening / phenomenon. Affect is realized most commonly in mental processes of reaction such as this pleases me, I hate ice- cream and he likes watching football games etc. Sometimes, affect can be realized by nouns such as his fear of spiders is well- known and her anger was perceivable in an instant etc.

Affect can be expressed in a positive / negative manner and it can be direct / implied. An example given by Martin and Rose (2003:27) of how affect is expressed is given below, with direct affect in bold and indirect affect is italicised:

He became very quiet. Withdrawn. Sometimes he would just press his face into his hands and shake uncontrollably. I realized he was drinking too much. Instead of resting at night, he would wander from window to window. He tried to hide his wild consuming fear, but I saw it.

In Martin and Rose’s (2003) example, one can see that a range of resources help build a picture of a negative emotional situation that a protagonist observes about someone else through including direct expressions of emotional states and physical behaviour and implicit expressions of emotion through extraordinary behaviour and metaphor.

Affect has an effect on the solidarity between speaker and audience. By appraising events or situations in affectual terms, the speaker/writer invites the audience to share that emotional response or that to see that the response was appropriate or well motivated and thus understandable.

There are possibly two subsequent scenarios with the use of affect in discourse with regards to solidarity, sympathy and empathy between speaker/writer (also the producer of the discourse) and audience in terms of affectual use from the speaker/writer. The first is that the feeling of solidarity between the audience and the speaker/writer will increase if the audience accepts the speaker/writer’s invitation to share affectual responses and if the audience understands the emotional standpoint of the speaker/writer. Through shared emotional responses and an understanding of why it is that the speaker/writer reacts in such a manner, there forms the possibility of the audience accepting the broader ideological aspects of the speaker/writer’s position. The second scenario, quite opposite to the first scenario is that solidarity between speaker/writer and audience may decrease if the audience does not take up the invitation to share affectual responses and if they do not understand or approve of the speaker/writer’s emotional responses. In this second scenario, the audience is also less likely to be open to the speaker/writer’s broader ideological view points.

Judgement: expressing judgement about people’s behaviour

Judgement involves expressing evaluations about ethics, morality or social values of people’s behaviour and shows the speaker’s evaluation of the mental, verbal or physical behaviour of others. People often judge others socio-culturally, against underlying social standards or what is deemed as the social norm and expected behaviour in society. People can behave in a manner that conforms to societal expectations or not, thus behaviour can be assessed as moral or immoral, legal or illegal, ethical or unethical, socially acceptable or unacceptable, normal or abnormal etc. Judgement is highly determined by cultural and ideological values and there are two broad categories of Judgement, including social sanction and social esteem.

Judgements of social sanction

Judgements of social sanction involve an assertion that some set of rules or regulations that are usually culturally codified, are at issue from the speaker / writer’s point of view. Those issues are usually legal or moral so that judgements of social sanction usually turn to legality and morality. For example, from a religious perspective, breaches of social sanction in Christian values will be deemed as ‘immoral’ and ‘mortal sins’ that risk religious punishment or sanctioning such as prayers or good deeds in compensation for one’s sins. Breaches of social sanction against the laws of a society for example will be deemed as crimes that risk legal punishment or sanctioning.

There are two kinds of judgements of social sanction, the first is the person’s propriety or ethical morality in complying with or deviating from the speaker’s own point of view of the social system. As Iedema, Feez and White (2004:201) point out:

The (ethics) system is concerned with assessing compliance with or defiance of a system of social necessity. To comply is to be judged favourably and to attract terms such as right, good, moral, virtuous, ethical, blessed, pious, law abiding, kind, caring, selfless, generous, forgiving, loyal, obedient, responsible, wholesome, modest. To defy these social necessities is to attract terms such as immoral, wrong, evil, corrupt, sinful, damned, mean, cruel, selfish, insensitive, jealous, envious, greedy, treacherous, rude, negligent, lewd, obscene etc.

The second type of judgements of social sanction evaluate the person’s veracity or truthfulness through lexical terms such as honest, truthful, credible, trustworthy, frank, deceitful, dishonest, unconvincing, inconsistent, hypocritical etc.

Judgements of social esteem

The second type of judgement, judgements of social esteem, involve the person judged to be lowered or raised in the esteem of their community, but which do not have moral or legal implications, so that they are not sins or crimes. Social esteem judgements are concerned with whether the person’s behaviour lives to up or fails to live up to socially desirable standards in terms of whether the person’s behaviour is customary, whether the person is competent and if the person is dependable etc. Iedema, Feez and White (2004:203) argue that positive values of social esteem can be associated with:

An increase in esteem in the eyes of the public while negative values diminish or destroy it. For example, an “outstanding” achievement, a “skilful” performance or a “plucky” display are all “admirable” while “abnormality”, “incompetence” or “laziness” are all contemptible or pitiable.

Judgements of social esteem can be divided into three sub-types that include judging the moral strength of the person where the person (or even group of persons) may be sanctioned or approved of, depending on whether they display moral strength or weakness; the second kind of social esteem judgement evaluates the complying to or departure from usuality and what is deemed as the social norm by the speaker / writer and the last sub-type of social esteem judgement evaluates how competent a person is at accomplishing something. Table 3.2 adapted after Eggins and Slade (1997:133) show the categories of judgement.

Table 3.2 Categories of Judgement adapted from and Eggins and Slade (1997:133)

|

Category |

Meaning |

Positive judgement |

Negative judgement |

|

Social sanction |

How moral? |

moral, upright, ethical |

immoral, wrong, cruel |

|

How believable? |

credible, honest, believable |

deceitful, dishonest |

|

|

Social esteem |

How committed? |

brave, strong, self- reliant |

cowardly, weak, irresponsible |

|

How usual / destined? |

lucky, blessed, fortunate, extraordinary, outstanding, remarkable, gifted, talented |

unfortunate, unlucky, cursed, ill- fated, peculiar, odd, freak |

|

|

How able? |

skilful, competent, dependable, reliable |

incompetent, unskilled |

As with affect, judgement can also be expressed in a positive or negative manner as shown in Table 3.2, and judgements may be passed explicitly or implicitly. Unlike affect however, judgements differ between personal (such as admiration / criticism) and moral (praise or condemnation). An example given by Martin and Rose (2003:29) of a direct condemnation, and expressing of a moral judgement (in bold) from the protagonist to another include:

Our leaders are too holy and innocent. And faceless. I can understand if Mr (F.W.) de Klerk says he didn’t know, but dammit, there must be a clique, there must have been someone out there who is still alive and who can give a face to ‘the orders from above’ for all the operations.

Appreciation: expressing an evaluation an object or process

Appreciation of things includes evaluations / attitudes towards a text or object such as films, books, music, paintings, sculptures, public buildings etc. or a process such as weather. Appreciation encompasses values that fall under the general heading of aesthetics, as well as a non-aesthetic category of ‘social valuation’ of abstract entities such as bodies of institutionalised texts such as policies, rules and regulations. Humans may also be evaluated appreciatively, for example, a handsome woman, a key figure etc. Appreciation can be registered in three ways, that of reaction, composition and valuation.

Reaction

A reaction to an object or person treated as an object, expresses how much or whether the speaker / writer finds the object pleasing. Reaction appreciation answers the question, “How good / bad did you think it was?”

Reaction can also be realized in two ways, by the impact the object makes on the viewer and by the viewer reacting to its quality. Examples of positive impact reaction would be, stunning, fascinating, dramatic, arresting etc. Examples of negative impact reaction would be, boring, monotonous, uninviting etc. A positive reaction to an object’s quality would be well crafted, beautiful, well made. A negative reaction to an object’s quality would be ugly, poorly made, shoddy.

Composition

Under composition, the texture of the text or process, its balance and composition is expressed in evaluations. The product or process is evaluated according to its makeup and how much it conforms to the various conventions of formal organization in the speaker / writer’s point of view and answers the question, “How did you find it put together?”

Composition of a text or process can be evaluated according to its complexity or detail. A positive evaluation of a text or process’s balance include unified, symmetrical, coherent, harmonious. A negative evaluation of a text or process’s balance include unbalanced, incoherent, incomplete, disproportionate. An evaluation of complexity includes, intricate, simple, exact, complicated.

Valuation

Valuation is concerned with the evaluation of the content or message of a text, object or process and answers the question, “How did you find / judge it?” A positive evaluation of valuation for example include, an inspiring lecture, a challenging task, a daring attempt. Negative examples of valuation include, a meaningless task, an irrelevant lecture, a thoughtless speech. Table 3.3 below shows the categories of appreciation, adapted from Eggins and Slade (1997:129)

Table 3.3 Categories of Appreciation, adapted from Eggins and Slade (1997:129)

|

Category |

Probe / Test |

Positive Examples |

Negative Examples |

|

Reaction |

How good / bad did you think it? |

arresting, pleasing, wonderful, fascinating, stunning |

uninviting, repulsive, horrible, boring, dull |

|

Composition |

How did you find it put together? |

simple, elegant, coherent, well crafted |

incoherent, crass, shoddy, complicated |

|

Valuation |

How did you find / judge it? |

inspiring, meaningful, challenging, daring, relevant |

shallow, meaningless, insignificant, useless |

Amplification: grading attitudes

Attitudes are gradable in the sense that attitudes can be strongly or weakly felt, one could be passionate or impassionate about someone or something. In this sense, amplification is not related to positive or negative attitudes but rather on the avidity of the speaker / writer. The three subcategories of amplification include enrichment, augmenting and mitigation.

Enrichment

Enrichment of attitudes can be done by the speaker / writer choosing to describe a person or an event / process in a coloured or non-neutral manner, saying for example, she killed them at the meeting today, to mean she made a convincing presentation at the meeting today.

There are two main sources for achieving attitudinal colouration. The first is that the speaker / writer chooses a lexical item which fuses a process or nominal meaning with a circumstance of manner to amplify the expression of how something is done, for example, the word whining can be used to describe a person who complains a lot in order to gain sympathy. The second manner of enrichment amplification is that the speaker / writer adds a comparative element which makes explicit the attitudinal meaning. For example, the phrase to run like hell, makes a hyperbolic / rhetorical comparison and the phrase to work like shit, uses in itself a negative evaluative word to lend colouration and amplification in attitude.

Augmenting

Augmenting involves intensifying the force of attitudes, such as she’s a good runner vs. she’s an amazingly fantastic runner. Several features help in intensifying the force of an evaluation, including the use of repetition such as she kept running vs. she just ran and ran and ran and grading words such as very, really, incredibly also provide the speaker with augmenting the force of the evaluation. Quantifying words such as some, many, a lot, all, are also resources to help calibrate degree of quantity with regards to things and processes.

Mitigation

Mitigation involves the playing down of the force of an evaluation. The result of which is that the speaker / writer can down-play their personal expression. Using lexical items that indicate uncertainly and hedging for example, help mitigate attitudes or personal expression and standpoint. For example, the word just in it’s just one cookie before dinner or it’s just a small scratch and the word only in it’s only a small scratch helps mitigate expression. Table 3.4, adapted from Eggins and Slade (1997:137) shows categories of amplification and their realizations.

Table 3.4 Categories of Amplification: general resources for grading and their realizations, Eggins and Slade (1997:137)

|

Category |

Meanings of categories |

Examples |

|

Enrichment |

Fusing an evaluative lexical item with the process |

whining |

|